Джефф Вандермеер - The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джефф Вандермеер - The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Notice, for example, the thorns. Observe how one’s gaze moves from left to right, to begin at the roses, tempting in the gentle wash of the watercolour, before thickening into thorns the closer one approaches the fish. Surely this symbolises the inaccessibility of the art object, the difficulty facing any critic who attempts to penetrate its mystery. Again, why is the fish singing? Why is it performing an act we cannot apprehend without the frame of the title? Is it triumphant? One could argue that its triumph is in its inscrutability, in the impossibility of seeing it as anything but what it is.

But the critic does not look cowed, only frowning in thought; he is sainted, even, he wears a halo! Could that indicate that the critic is dead? Is the Singing of the Fish synonymous with the Death of the Critic? Can the one exist without the other? Finale, spell the ribbons—or are they scarves? The looping of the letters is rather noose-like—hearkening back, perhaps, to Odin’s gallows-heritage? The more answers one finds, the more thorns, or questions, one encounters!

This is terribly exciting work, you must understand. There is a terrible burden to be shouldered here, in being the first to offer a detailed analysis of the fish in print. Mehler’s death-desk scribbles offer little in the way of illumination, except for his gouged-out exclamations about palettes and colour. These are useless. Of course the palette has colour on it—the whole piece is washed in a pale rose watercolour, and the palette is shaped for holding oils or acrylic. Ah, but is that irony at work? Oh, of course! It is a pen-and-ink drawing—and look, there, the inkwell and the feathers! She has appropriated the critic’s tools ! That is why the palette has no colour on it—the palette is her vulnerability, the colours her Achilles’ heel! The palette has no colour on it. The fish has sprung fully formed from it—the fish is the palette’s colour! The only colour is in the end— Finale, in colour, in the colour that the palette lacks—the colour the fish brings! The devilish detail of it! Frogs begin as fish! They die and are resurrected as singing fish! Oh, I see it all, Ms. Abendroth, I do, I see! I can hear it clear as a bell!

Such, at any rate, would likely have been Mehler’s statements, had he been able to communicate them in something other than the blood and wood-dust beneath his fingernails. The piece seems very nice, and it is testament to Dr. Lambshead’s discerning taste that he sought to preserve so excellent a thing in his Cabinet. 8

ENDNOTES

1. Stephen Kurtz, ed. The Early Journals of Edith Abendroth, vol. III, p. 67 (Routledge, 1959)

2. Ibid., vol. VI, p. 98

3. Die Spitzer Feder, April 1856, p. 24

4. Ibid., October 1856, p. 32

5. Nussbaum, Ursula. Loves That Did Not Know Their Names: Lesbian Desire in Edith Abendroth’s Early Journals , p. 134 (Ashgate, 1979)

6. Kurtz, Stephen. Frogs, Frocks, and Fol-de-Rol: The Mirth and Madness of Edith Abendroth , p. 91 (Routledge, 1961)

7. Ibid., p. 113

8. While the main body of this essay and all previous endnotes were the work of Amal El-Mohtar, the final paragraph was appended by a friend who has chosen to remain anonymous. This friend would like to make clear that Ms. El-Mohtar’s unorthodox approach to the essay’s conclusion is to be read as ironic, and certainly has nothing to do with the fact that she has since withdrawn into the seclusion afforded by a village in the southwest of Cornwall, where she spends her days in pursuit of garden fairies to dissect for her doctoral thesis, and her nights in tormented, guilt-wracked sobs for subjecting them to the cruelty of iron.

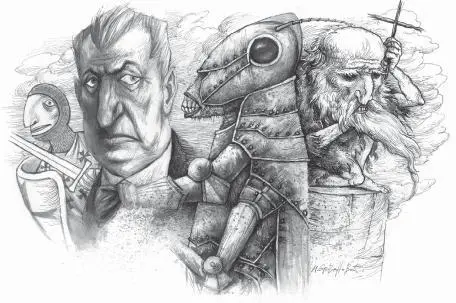

The Armor of Sir Locust

As Dictated to Stepan Chapman by Dr. Thackery Lambshead, 1998

Until recently, I looked forward to cataloging my collection of souvenirs and curios. Now, in retirement, I finally have the time, and it turns out that the job is an endless drudgery. It further turns out that I know nothing worth recording about my possessions. I only know that I acquired some of these things during my years of constant travel. Others could explicate them with better success than I. My memory is not what it was.

This thing, for example. I had to wire it together from various pieces. Bought it in a canvas box from an antique store in Cairo. Got it for peanuts. Had it appraised at the London Natural History. The docent said it was priceless. Hard to know what that means, coming from a docent.

Ivica Stevanovic’s “Armor Montage” incorporating Dr. Lambshead, as first published along with the doctor’s account in the magazine Armor & Codpiece Quarterly (Winter 2000).

It’s unusual, these days, to own a suit of medieval armor, but this specimen is more than unusual, it’s downright peculiar. The metal’s been assayed. I’m assured that it’s an alloy of tin and bronze characteristic of the Second Crusade. Copper grommets—probably a later addition. Scraps of leather, hung with buckles.

The first time you see this thing, a series of questions enter your mind. Such as: Is it armor for a man or for a horse? And if it’s for a man, why has it got armor for four arms? And if it’s for a horse, why has it got armor for six legs? That’s three questions already, and they just keep coming. For as long as the legend of Sir Locust has been recited, there have been variants, and the variants raise questions of their own. Was he originally a soldier? Was he a priest? Was he a locust that grew and grew and somehow, by some bizarre spontaneous recombinant mutation, took on human attributes? Was he a man who was cursed, at puberty perhaps, with the attributes of a locust? Too many questions.

Sometimes I entertain the ghoulish notion that perhaps this armor is no artifact at all, but rather a mummified skeleton, scooped out subsequent to burial and grave robbery. But then I look closely at the hooks and loops and chain mail, and I remember that insects, of whatever size, are not made of metal. But a custom-forged spring-wound machine, an engine of war disguised as a person, that would be made of metal. Speculation is impossible. Let’s examine the written records.

Sir Locust appears in several of the illuminated annals of the Second Crusade. His presence is noted at certain battles. One such text, which still exists in scattered fragments, is The True Chronicle of Sir Locust the Unlikely . It reports that Sir Locust had a nemesis, an opposite number on the Saracen side of the conflict, who was called the Mullah Barleyworm. This priest of Allah, so we’re told, sent a series of three assassins against Sir Locust. None returned. At this juncture, the mullah confronted the French knight directly. They joined combat, and neither survived. I’m leaving out all the good parts. My time is limited, and my collection is extensive.

For instance, I’m leaving out the love interest. Evangelette of Lombardy was Sir Locust’s lady. After his death, she cherished a bloodstained silk scarf, and so on. I’m sure that he wrote her countless sonnets from the front. If the Second Crusade had a front. The Christians lost that crusade, as you may recall.

So now we have a cast of characters all constellated around this dented suit of giant insect armor. Once, the Mullah Barleyworm traveled to France in disguise and kidnapped the Lady Evangelette. Word reached our hero. What a kick in the head for him. He followed his archenemy to Syria but could only effect his lady’s release by giving himself into Barleyworm’s power, as they say in gothic novels. Torture followed, and rooms filling with water, walls sprouting spikes, bottomless chasms, impregnable towers, the jaws of death, all the usual flummery. Also there was some question as to whether the lady actually wanted to be rescued, having fallen in love with her captor in the time-honored masochistic tradition. Legend has it she was drugged. That’s just what Crusaders would expect from an infidel.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.