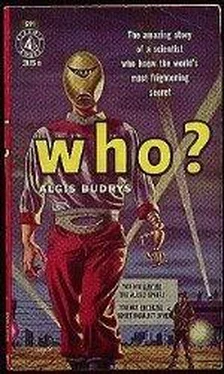

Algis Budrys - Who?

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Algis Budrys - Who?» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1958, Издательство: Pyramid Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Who?

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pyramid Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1958

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Who?: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Who?»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nominated for Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1958.

Who? — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Who?», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I still don’t follow you,” Lucas said, frowning.

“Look — these guys aren’t morons. They’re pretty damned bright, or they wouldn’t be here. But the only way they’ve ever been taught to learn something is to memorize it. If you throw a lot of new stuff at them in a hurry, they’ll still memorize it — but they haven’t got time to think. They just stuff in words, and when it comes time to show what they know, they unroll a piece. Yard goods.

“I say that’s a hell of a dangerous thing to have going on. I say anybody with brains ought to realize what he’s doing to himself when he stuffs facts down indiscriminately. I say anybody who did realize it would want to do something about it. But these clucks aren’t even bothered by it enough to wrinkle their foreheads. So, considering everything, I say they may have brains, but they don’t have brains enough.

“Now, you I’ve watched. When I sit here looking at you doing up your notes, it’s a pleasure. Here’s a guy with a look on his face as if he’s looking at a love letter, for Christ’s sake, when he’s reading an electronics text. Here’s a guy who fills out project reports like a man building a good watch. Here’s a guy that’s chewing before he swallows — here’s a guy who’s doing something with what they give them. Here, when you come right down to it, is a guy this place was really set up to produce.”

Lucas raised his eyebrows. “Me?”

“You. I get around. I guess I’ve at least taken a look at every bird on this campus. There’s a few like you on the faculty, but none in the student body. A few come close, but nobody touches you. That’s why I say out of all the students here, all four classes, you’re the guy to watch. You’re the guy who’s going to be really big in his field, I don’t give a damn if it’s civil engineering or nuclear dynamics.”

“Electronic physics, I think.”

“O.K., electronic physics. My money’s on the Commies to be really worried about you in a few years’ time.”

Lucas blinked. He was completely overwhelmed. “I’m the illegitimate son of Guglielmo Marconi,” he said in reply. “You notice the similarity in names.” But he couldn’t do more with that defense than to put a temporary stop to Heywood’s trend of conversation. He had to think it over — think hard, to arrange all this new data in its proper order.In the first place, here was the brand-new notion that a difference from other people was not necessarily bad. Then, there was the idea that somebody actually thought enough of him to observe his behavior and analyze it. That was not something he expected from people other than his parents. And, of course, the second conclusion led to a third. If Frank Heywood was thinking along lines like these, and if he could see what other people couldn’t, then Frank, too, was a person different from most.That could mean a great deal. It could mean that he and Frank could at least talk to each other. Certainly it meant that Frank, despite his disclaimer, was just as capable as he — perhaps more so, since Frank had seen it and he had not.In many ways, Lucas found this an attractive train of thought. If he accepted any part of it, it automatically meant he also accepted the idea that he was some kind of genius. That in itself made him look at the whole hypothesis suspiciously. But he had very little or no real evidence to refute it. In fact, it was the kind of hypothesis that made it possible to reinterpret his whole life, and thus reinterpret every piece of evidence that might have stood against it.

For several more weeks, he went through a period of great emotional intoxication, convinced that he had finally come to understand himself. In those weeks, he and Frank talked about whatever interested Lucas at the moment, and carried on serious discussions long into the night. But the feeling of being two geniuses together was an essential part of it, and one night Lucas thought to ask Frank how he was doing at his studies.

“Me? I’m doing fine. Half a point over passing grade, steady as a chalkline.”

“ Half a point?”

Heywood grinned. “You go to your church and I’ll go to mine. I’ll get a sheepskin that says Massachusetts Institute of Technology on it, the same as yours.”

“Yes, but it’s not the diploma—”

“—it’s what you know? Sure, if you’re planning to go on from there. I could, to be completely honest, give even you a run for the money when it comes to that. But why the hell should I? I’m not going to sweat my caliones off at Yucca Flat for the next forty years, draw my pension, and retire. Uh-uh. I’m going to take that B.S. from MIT and make it my entrance ticket into some government bureau, where I’ll spend the next forty years sitting behind a desk, freezing my caliones off in an air-conditioned office, and someday I’ll retire on a bigger pension.”

“And-and that’s all?”

Heywood chuckled. “That’s all, paisan.”

“It sounds so God-damned empty I could spit. A guy with your brains, planning a life like that.”

Heywood grinned and spread his hands. “There it is, though. So why should I kill myself here? This way I get by, and I’ve got lots of free time.” He grinned again. “I get to have long talks with my roommate, I get to run around and see other people — hell, amico, there’s no sweat this way. And it takes a guy with brains to pull it in a grind house like Tech, I might add.”

It was the total waste of those brains that appalled Lucas. He found it impossible to understand and difficult to like. Certainly, it destroyed the mood of the past month.He drew back into his shell after that. He was not hostile to Heywood, or anything like it, but he let the friendship die quickly. He lost, with it, any idea of being a genius. In time he even forgot that he had ever come close to making a fool of himself over it, though occasionally, when something went especially well for him in his later life, the idle thought would crop up to be instantly, and embarrassedly, suppressed.

He and Heywood finished their undergraduate work, still roommates. Heywood was once more the perfect person for one small room with Lucas Martino, and seemed not to mind Lucas’ long periods of complete silence. Sometimes Lucas saw him sitting and watching him.After they graduated, Heywood left Boston, and, as far as Lucas was concerned, disappeared. And it was only some years later that one of the men for whom he was a graduate assistant came to him and said, “This hypothesis you were talking about, Martino — it might be worth your doing a paper on it.”

So Heywood missed the birth of the K-Eighty-Eight completely, and Lucas Martino, for his part, once again had something to claim all his attention and keep him from thinking about the unanswered problems in his mind.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

1

Edmund Starke had become an old man, living alone in a rented four-room bungalow on the edge of Bridgetown. He had dried to leathery hardness, his muscles turning into strings beneath his brittle skin, his veins thick and blue. The hair was gone from the top of his skull, revealing the hollows and ridges in the bone. His glasses were thick, and clumsy in their cheap frames. His jaw was set, thrust forward past his upper teeth, and his eyes were habitually narrowed. Like most old men, he slept little, resting in short naps rather than for very long at any one time. He spent his waking hours reading technical journals and working on an elementary physics textbook which, he felt suspiciously, was turning out to resemble every elementary physics text written before it.

Today he was sitting in the front room, twisting the spine of a journal in his fingers and peering across the room at the opposite wall. He heard footsteps on the dark porch outside and waited for the sound of the bell. When it came, he got up in his night robe and slippers, walked slowly to the door and opened it.A big man stood in the doorway, his face bandaged bulkily, the collar of his coat pulled up and his hat low over his eyes. The light from the room glittered blankly on dark glasses.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Who?»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Who?» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Who?» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.