“No…”

“Whatever you can tell us might help us find him.”

“I don’t see how.” Pause. “Well. Once he hit the Lewisson boy hard enough he had to get stitches over his eye. Other times it was just scuffles. Maybe a black eye or two. Sometimes Orrin got the worst of it. Sometimes not.” She added, “He always felt bad about it afterward.”

“Okay, thank you,” Bose said. “Anything else Orrin talked about this morning that you can recall? Anything at all, even if it seems unimportant.”

“No. Just the weather, like I said. He was interested in the weather report coming over the radio in the coffee shop. They’re calling for heavy rain tonight. That excited him. ‘I guess it’s tonight,’ he said. ‘Tonight’s the night.’”

“Any idea what he meant by that?”

“Well, he always did like storms. You know. The thunder and all.”

* * *

Bose convinced Ariel to stay in her room, “otherwise I’ll end up looking for the both of you.” And Ariel had calmed down enough to see the sense in it.

“You’ll call me, though, right? Soon as you know anything?”

“I’ll call you whether we know anything or not.”

Back in the motel lobby, Bose talked to the desk clerk for a few minutes. Orrin had been waiting for the downtown bus, the clerk said. No, he hadn’t actually seen Orrin get on. Just noticed him waiting out there. Skinny guy in torn jeans and a yellow T-shirt standing in the sun by the side of the road. “Begging for heat stroke in this weather, if you ask me. Those buses only come along every forty-five minutes.”

“So what do we do?” Sandra asked when Bose had finished.

“Depends. Maybe you want to stay here with Ariel?”

“Or maybe I don’t.”

“I can think of a couple of places we might look.”

“You’re saying you know where he went?”

“I have an idea or two,” Bose said.

Chapter Twenty-two

Allison’s Story

Isaac Dvali explained how he’d turned off the Network surveillance. Turk sat warily still, watching Isaac, watching me.

“It’s true,” I said when Isaac finished, and I told him the rest of it: that I’d talked to Isaac days ago, that Isaac knew about our plan, and that (at least for the moment) the Network couldn’t hear a word we said.

I wasn’t sure he believed me until he stood up and came across the room and we looked at each other, our first honest look since we had begun planning our escape. Then we were in each other’s arms, trying to say all the things we wanted to say and managing only a happy-sad incoherency. But words didn’t matter. It was enough to be able to hold him without making a lie of it. Then my hand touched the node at the back of his neck: a patch of papery skin, a fleshy bump. He flinched, and we drew apart.

He turned to Isaac. “Thank you for doing this—”

“You’re welcome.”

“—but it’s a little confusing. I knew Isaac Dvali back in the Equatorian desert. You look like him, allowing for what happened, and I know they rebuilt you from Isaac’s body. But a lot of you must be pure Vox. And to be honest, you don’t sound much like the Isaac I knew.”

“I’m not the Isaac you knew. There isn’t a word for what I am.”

Turk was looking at him with Networked attention, reading the invisible signs. “What I’m saying is, I don’t understand why you’re here. I don’t know what you want.”

Isaac’s smile disappeared and a cold light came into his eyes, a light even I could see. “It doesn’t matter what I want. It never did! I didn’t ask to be injected with Hypothetical biotechnology when I was in my mother’s womb. I didn’t ask to be cycled through the temporal Arch, I didn’t ask to be brought back to life when I was decently dead. What I wanted was never germane. It isn’t now. My neural functions are shared with processors embedded in the Network. I’m chained to Vox, I can’t exist without it, and Vox is about to be consumed by something… incomprehensible.” He made a visible effort to control himself. “The Hypotheticals don’t care about anything as trivially brief as a human life. It’s the Coryphaeus that interests them. When the Hypothetical machines reach Vox, they’ll absorb the Coryphaeus and dismantle Vox Core. Nothing human will survive.”

I said, “How do you know that?”

“I can’t talk to the Hypotheticals—I’m not what Oscar thinks I am—but I can hear them ticking out in the dark. Not their thoughts—their appetites. ” His face went slack and he closed his eyes—listening, maybe. Then he shook his head and looked at Turk. “You were there when I was in pain. Not because you thought I was a god. Not because you could use me. Not like the doctors, hovering over me like crows over carrion.”

“That’s little enough,” Turk said.

“If you can save yourselves, I want to help. That’s also little enough. ”

“What about you?” I asked.

A trace of a smile returned to his face, but it was bitter. “If I can’t leave, I might be able to hide. I’ve been trying to create a protected space inside the Network. Not for my body but for my self. I mean to try. But the Hypotheticals are very powerful. And the Coryphaeus… the Coryphaeus is insane.”

* * *

The Coryphaeus is insane.

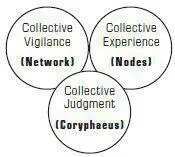

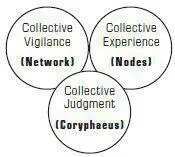

As Treya I hadn’t given the Coryphaeus much thought. Few of us did. The Coryphaeus was an abstraction, a name for the processors that quietly and invisibly mediated between Network and node. Our teachers had shown us a diagram to explain it:

—and that was as much as we had ever wanted or needed to know. The system was stable, self-protecting, self-perpetuating, and it had worked flawlessly for five centuries. What could it mean, then, to say that the Coryphaeus had gone mad?

The problem was the Voxish prophecies. Our founders had written them into the Coryphaeus as unalterable axioms—embedded truths, permanently exempt from debate or revision. That hadn’t mattered when the rapture of the Hypotheticals was a distant goal toward which we moved in gradual increments. But now we had come to the blunt end of the question. Prophecy had collided with reality, and the obvious inference—that the prophecies might have been mistaken—was a possibility the Coryphaeus was forbidden to consider.

That conflict was being played out in the surveillance and infrastructure systems that bound together our lives and our technology; it was being played out in the limbic interfaces and private emotions of everyone who wore a node. “What makes it especially dangerous,” Isaac said, “is that we can’t predict the result. The most likely outcome is an asymptotic trend toward self-destructive behavior in both the organic and inanimate aspects of the system.” He added, “It’s already happening… more quickly than I anticipated.”

I asked him what he meant, then wished I hadn’t.

“The end of Vox is days away. That means there’s no need for a surplus food supply. Or surplus people, if they’re not a willing part of the process.” He looked away, as if he couldn’t bear to meet our eyes. “The Coryphaeus is killing the last of the Farmers.”

* * *

I refused to believe it until I had seen evidence. As soon as Isaac left I rode vertical transit to one of the high towers and found a panoramic window. It was night, but the sky was unusually clear and the moon was bright on the northern horizon.

The Farmers had lived in the hollow spaces under the outlying islands of the Vox archipelago. They had numbered about thirty thousand souls before the rebellion—fewer, but at least half that many, after.

Читать дальше