As the Project Orion study continued, it became evident that Orion “interceptors” could be capable of velocities in excess of 30 miles (50 kilometers) per second. Some conceptual versions could lift from Earth under their own nuclear drive, unfortunately leaving behind a huge wake of radioactive particles. Variants might ride as the second stage of a Saturn V rocket, exhausting their A-bombs well above Earth’s delicate biosphere.

The high time for Project Orion was in 1961-1963. NASA had been commissioned by President Kennedy to deliver and return humans from the Moon before 1970. Most analysts preferred the Saturn V booster to launch the Moon ships, but this rocket had not yet been tested. So a number of back-ups were suggested. One was Orion.

In this heady period, Dyson, Taylor and their associates investigated the interplanetary potential of Orion. As a Saturn V upper stage, it had the potential of ferrying astronauts to Mars on month-long journeys. Habitats, rovers, greenhouses and livestock could come along as well.

But alas, it was not to be. The Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty dampened the prospects for Orion. And the success of Saturn V doomed it. Before the first Lunar Modules swooped down over the lunar plains, Orion and its extensive documentation seemed headed for storage in some super-secret government depository, perhaps located next to the box containing Indiana Jones’s Ark of the Covenant.

Freeman Dyson was angry. And Freeman Dyson distrusted large government bureaucracies. So he methodically hatched a scheme to save Project Orion from oblivion.

Being a physicist, Dyson planned to publish a paper describing the potential of Orion in a journal. But most physics, astronomy, and astronautics journals have circulations of only a few thousand. He chose to publish in Physics Today , a semi-popular monthly organ of The American Institute of Physics. Many public and university libraries subscribe to this magazine—its monthly readership would therefore be much larger than that of more technical physics journals. Dyson planned a paper that would outline the concept of Orion in visionary terms, and do so in a manner that would not violate his oath of secrecy.

Of course he had to use clever approximations. One was the yield in equivalent megatons of TNT of a deuterium-fueled thermonuclear explosive. Dyson knew that the USSR had just air tested the largest H-bomb ever exploded. The yield of the test was well established and the type of aircraft carrying the device had been announced. Dyson probably could have exactly stated the yield of a fusion explosive—instead, he consulted a standard reference ( Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft ) and used the payload capacity of the Soviet bomber.

Published in late 1968, Dyson’s paper established him as an early hero of the “Interstellar Movement.” Even with his many approximations, he demonstrated that huge, multi-kilometer fusion-pulse world ships could be constructed that would take up to one thousand years to reach the nearest stars. If the entire US/USSR 1968-vintage thermonuclear arsenals had been devoted to Project Orion, as many as 20,000 people could have been relocated to the Alpha / Proxima Centauri system. What a happy use for the bombs!

Projects Daedalus and Icarus —The BIS follows Up

Now that Dyson and Taylor had opened the “Interstellar Door,” other groups began their own studies. The British Interplanetary Society (BIS), which had studied Moon flight decades before the Apollo Project, was ideally situated to conduct a follow-on study to Orion. British researchers Alan Bond and Anthony Martin directed this study, dubbed Project Daedalus , during the 1970’s. The original Daedalus , a mythological Athenian architect, had escaped imprisonment in Crete with the aid of flapping wings handily crafted from goose feathers.

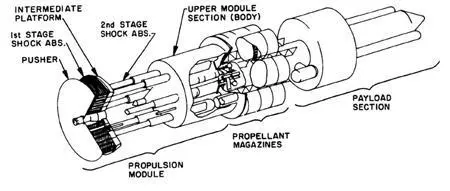

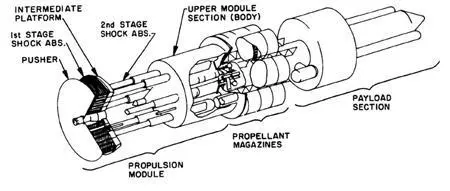

It was soon determined that the modern Daedalus , although inspired by the Orion conceptual breakthrough, would be a bit different. Several problems were acknowledged with the Orion concept. One was scale—an Orion starship (such as the pulsed thermonuclear rocket shown schematically in Figure 2) would be huge even if its payload were small. This was due to the size of the equipment necessary to deflect the copious particles emitted by even a small thermonuclear blast. Another issue was psychological—how would the crew and passengers of a starship react to a megaton-sized explosion going off every few seconds, at a distance of only a kilometer or so? Finally, it is difficult to conceive of any real-world scenario in which nuclear superpowers would allow use of their arsenals in such a constructive endeavor.

Figure 2. Artist concept of a Project Orion nuclear pulse spacecraft. (Image courtesy of NASA.)

Daedalus evolved as a kid brother to Orion. Instead of using the dramatic thermonuclear-pulse drive, it used a somewhat tamer approach—inertial fusion. Small micropellets of fusion fuel were to be ejected into a combustion chamber equipped with strong magnetic fields. Instead of ignition by a fission trigger, these pellets were to be heated to fusion temperatures and condensed to fusion densities by an array of focused laser or electron beams.

Researchers involved in the effort spent a good deal of time considering fusion fuel cycles. They rejected the deuterium-tritium (D-T) and deuterium-deuterium (D-D) fusion reactions under active consideration for terrestrial energy production. Although cleaner than fission, the copious thermal neutrons produced by these reactions would rapidly irradiate the spacecraft. Instead, they settled on a reaction between a low-mass form of helium (Helium-3) and deuterium. The products of this reaction are electrically charged particles—these are relatively easy to focus and expel with the aid of powerful magnetic fields.

Although the Helium-3/D reaction is the second easiest to ignite after D-T, it has one significant drawback. Helium-3 is very, very rare in the terrestrial environment. Starship designers were faced with four alternatives to obtain the necessary tens of millions of kilograms of this substance.

1. They could pepper the surface of the Earth or Moon with breeder reactors, which produce more nuclear fuel than they consume to produce it.2. Since Helium-3 is a trace component of the solar wind of ions ejected from our Sun, some form of superconducting electromagnetic scoop could mine the solar wind for this isotope—but high temperatures in the inner solar system might render superconducting scoops difficult to build and maintain.3. Tiny amounts of He-3 had been deposited in the upper layers of lunar soil as evidenced by samples returned by Apollo astronauts—but at that time nobody knew how the He-3 concentration varied with depth in lunar soils and how feasible lunar mining might actually be.4. What they opted for was the fourth alternative: He-3 is found in the atmospheres of giant planets. Perhaps a series of robotic helium mines suspended by balloons in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter would be the answer.

Although the Daedalus engine could in concept be used to accelerate and decelerate a “thousand-year ark,” the initial application was expected to be robotic probes that could be accelerated to about 10% the speed of light (0.1c) and then fly through the destination star system. In the 1970s, it was (erroneously) suspected that the second nearest star—a red dwarf called Barnard’s star at a distance of about six light years from the Sun—had Jupiter-sized planets. So Barnard’s Star was selected for the hypothetical star mission.

Читать дальше