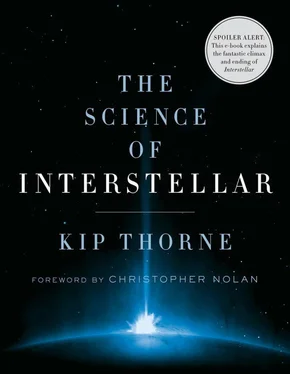

Kip Thorne

THE SCIENCE OF INTERSTELLAR

One of the great pleasures of working on Interstellar has been getting to know Kip Thorne. His infectious enthusiasm for science was obvious from our first conversation, as was his reluctance to proffer half-formed opinions. His approach to all the narrative challenges that I threw him was always calm, measured and above all, scientific . In trying to keep me on the path of plausibility, he never showed impatience with my unwillingness to accept things on trust (although my two-week challenge to his faster-than-light prohibition might have elicited a gentle sigh).

He saw his role not as science police, but as narrative collaborator—scouring scientific journals and academic papers for solutions to corners I’d written myself into. Kip has taught me the defining characteristic of science—its humility in the face of nature’s surprises. This attitude allowed him to enjoy the possibilities that speculative fiction presented for attacking paradox and unknowability from a different angle—storytelling. This book is ample demonstration of Kip’s lively imagination and his relentless drive to make science accessible to those of us not possessed of his massive intellect or his immense body of knowledge. He wants people to understand and get excited about the crazy truths of our universe. This book is structured to let the reader dip in to a topic as deeply as their affinity for science prompts them—no one is left behind, and everyone gets to experience some of the fun I had trying to keep up with Kip’s agile mind.

Christopher Nolan Los Angeles, California July 29, 2014

I’ve had a half-century-long career as a scientist. It’s been joyously fun (most of the time), and has given me a powerful perspective on our world and the universe.

As a child and later as a teenager, I was motivated to become a scientist by reading science fiction by Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and others, and popular science books by Asimov and the physicist George Gamow. To them I owe so much. I’ve long wanted to repay that debt by passing their message on to the next generation; by enticing youths and adults alike into the world of science, real science; by explaining to nonscientists how science works, and what great power it brings to us as individuals, to our civilization, and to the human race.

Christopher Nolan’s film Interstellar is an ideal messenger for that. I had the great luck (and it was luck) to be involved with Interstellar from its inception. I helped Nolan and others weave real science into the film’s fabric.

Much of Interstellar’ s science is at or just beyond today’s frontiers of human understanding. This adds to the film’s mystique, and it gives me an opportunity to explain the differences between firm science, educated guesses, and speculation. It lets me describe how scientists take ideas that begin as speculation, and prove them wrong or transform them into educated guesses or firm science.

I do this in two ways: First, I explain what is known today about phenomena seen in the movie (black holes, wormholes, singularities, the fifth dimension, and the like), and I explain how we learned what we know, and how we hope to master the unknown. Second, I interpret , from a scientist’s viewpoint, what we see in Interstellar , much as an art critic or ordinary viewer interprets a Picasso painting.

My interpretation is often a description of what I imagine might be going on behind the scenes: the physics of the black hole Gargantua, its singularities, horizon, and visual appearance; how Gargantua’s tidal gravity could generate 4000-foot water waves on Miller’s planet; how the tesseract, an object with four space dimensions, could transport three-dimensional Cooper through the five-dimensional bulk;…

Sometimes my interpretation is an extrapolation of Interstellar ’s story beyond what we see in the movie; for example, how Professor Brand, long before the movie began, might have discovered the wormhole, via gravitational waves that traveled from a neutron star near Gargantua through the wormhole to Earth.

These interpretations, of course, are my own. They are not endorsed by Christopher Nolan any more than an art critic’s interpretations were endorsed by Pablo Picasso. They are my vehicle for describing some wonderful science.

Some segments of this book may be rough going. That’s the nature of real science. It requires thought. Sometimes deep thought. But thinking can be rewarding. You can just skip the rough parts, or you can struggle to understand. If your struggle is fruitless, then that’s my fault, not yours, and I apologize.

I hope that at least once you find yourself, in the dead of night, half asleep, puzzling over something I have written, as I puzzled at night over questions that Christopher Nolan asked me when he was perfecting his screenplay. And I especially hope that, at least once in the dead of night, as you puzzle, you experience a Eureka moment, as I often did with Nolan’s questions.

I’m grateful to Christopher Nolan, Jonathan Nolan, Emma Thomas, Lynda Obst, and Steven Spielberg for welcoming me into Hollywood, and giving me this wonderful opportunity to fulfill my dream, to pass on to the next generation my message of the beauty, the fascination, and the power of science.

Kip Thorne Pasadena, California May 15, 2014

1

A Scientist in Hollywood:

THE GENESIS OF INTERSTELLAR

Lynda Obst, My Hollywood Partner

The seed for Interstellar was a failed romance that warped into a creative friendship and partnership.

In September 1980, my friend Carl Sagan phoned me. He knew I was a single father, raising a teenaged daughter (or trying to do so; I wasn’t very good at it), and living a Southern California single’s life (I was only a bit better at that), while pursuing a theoretical physics career (at that I was a lot better).

Carl called to propose a blind date. A date with Lynda Obst to attend the world premier of Carl’s forthcoming television series, Cosmos .

Lynda, a brilliant and beautiful counterculture-and-science editor for the New York Times Magazine , was recently transplanted to Los Angeles. She had been dragged there kicking and screaming by her husband, which contributed to their separation. Making the best of a seemingly bad situation, Lynda was trying to break into the movie business by formulating the concepts for a movie called Flashdance.

The Cosmos premier was a black-tie event at the Griffith Observatory. Klutz that I was, I wore a baby-blue tuxedo. Everybody who was anybody in Los Angeles was there. I was completely out of my element, and had a glorious time.

For the next two years, Lynda and I dated on and off. But the chemistry just wasn’t right. Her intensity enthralled and exhausted me. I debated whether the exhaustion was worth the highs, but the choice wasn’t mine. Perhaps it was my velour shirts and double-knit pants; I don’t know. Lynda soon lost romantic interest in me, but something better was growing: a lasting and creative friendship and partnership between two very different people, from very different worlds.

Fast-forward to October 2005, another of our occasional one-on-one dinners, where conversation would range from recent cosmological discoveries, to left-wing politics, to great food, to the shifting sands of moviemaking. Lynda by now was among Hollywood’s most accomplished and versatile producers ( Flashdance, The Fisher King, Contact, How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days ). I had married. My wife, Carolee Winstein, had become best friends with Lynda. And I’d not done badly in the world of physics.

Читать дальше