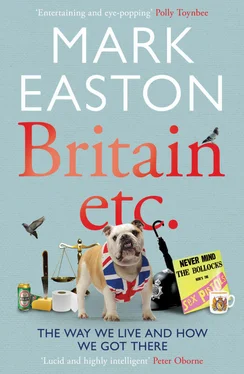

Mark Easton

BRITAIN Etc.

The Way We Live and How We Got There

This book grew in the crannies. It has been an interstitial project, squeezed into the tiny spaces between my (full-time) job and my (full-time) family. So, it simply could not have been written without the support and forbearance of my colleagues, my children and, above all, my wife.

Particular thanks go to Andrew Gordon who planted the seed, Jo Whitford who helped harvest and box the crop and Mike Jones who steered the cart to market. I am hugely grateful to Mike O’Connor, Malcolm Balen, John Kampfner, John Humphrys, Brian Higgs, among many others, who gave sane advice and welcome encouragement along the way. I must also mention my late father, Stephen Easton, whose genius as a bookman guided me even in his last days.

My children — Flora, Eliza, Annis and Ed — deserve recognition for generously putting up with my alphabetical obsessions as well as denial of access to the home computer. But greatest thanks go to my wife Antonia who was ally, advisor and inspiration. She helped me find the space to write and, just as importantly, told me when it was time to stop.

As I write, Britain finds itself under the international spotlight: the London Olympics and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee are extravagant and ostentatious shows in which the United Kingdom is placed centre stage. The world is watching us, studying our ways and trying to make sense of our culture and our values.

The British themselves, meanwhile, are in a period of uneasy self-reflection. Institutional scandals have rocked the pillars of our state: Parliament, the City, police and press. There is bewilderment at rioting and looting that, over the course of a few days and nights in the summer of 2011, forced us to confront some troubling truths. After decades of getting inexorably richer, the squeeze of belt-tightening austerity is straining the threads holding our society together.

This is not a bad time, then, to consider contemporary Britain: what kind of place is it? Since first joining my local paper in 1978, I have attempted to answer that question by peering through a standard lens — the familiar perspective of daily news and current affairs. But so often this blinkered view confounds rather than clarifies. The picture is neither wide enough nor detailed enough to grasp the real story. As the electronics salesman might put it, we need a 3D HD 55" plasma screen and we are watching on a 12" cathode ray tube telly. So, in thinking how to write this book, I sought inspiration from two pioneering British lens-masters who made it possible for people to see the world in new and wonderful ways.

The first I found at a Palo Alto ranch in June 1878, a wild-bearded man in a wide-brimmed hat. Under a bright Californian sky, crowds watched as Eadweard Muybridge took a series of photographs that, for the first time, revealed the mysteries of equine motion. The speed of a galloping horse was too fast for the naked eye to see precisely how the animal moved. Only by slowing the action down to a series of stop-motion frames, captured by a line of triggered cameras, was Muybridge able to answer the much-debated question as to whether all four hooves were ever airborne at the same time. (Answer: yes, but tucked under, not outstretched as many artists had assumed.)

The second of my photographic guides I discovered in his garden three decades later, behind a suburban home in north London. Percy Smith was working on a film that also allowed people to see the world in a new way. When The Birth of a Flower was shown to British cinemagoers in 1910, it is reported the audience broke into riotous applause. Smith’s use of time-lapse photography achieved the opposite of Muybridge, accelerating the action of days into a few seconds. Plants bloomed before astonished eyes: hyacinths, lilies and roses. One journalist described the result as ‘the highest achievement yet obtained in the combined efforts of science, art and enterprise’.

What would contemporary Britain look like through Muybridge’s or Smith’s lenses? Instead of just hyacinths or horses, I resolved to apply their techniques to numerous and varied aspects of British life: the time-lapse sweep through history and the stop-motion analysis of the crucial detail.

The alphabet would structure my journey but serendipity and curiosity would decide direction. The idea was not to stick to well-worn paths but to search for a better understanding of Britain wherever impulse led. So, yes, A was for alcohol — a stiff whisky to start me off. But my wandering inspired me to examine my homeland’s relationship with foreigners and computers and vegetables and drugs and dogs and youth and silly hats and beggars and toilets and cheese, and more.

Some subjects may appear almost frivolous, but each strand of the national fabric I chose to follow revealed something unexpected, fascinating and profound. At times, the detail prompted me to laugh aloud; at others almost to despair. When woven together, the threads formed a coherent canvas, a portrait of contemporary Britain simultaneously inspiring and troubling. In the background, a weather-beaten landscape shaped by the glacial and seismic forces of history; in the foreground, a diverse crowd moving, eating, kissing, arguing, laughing, working, drinking, worrying, studying and wearing silly hats.

After more than thirty years chronicling Britain’s story for newspapers, radio and television, I thought I had a handle on what the place is like. But my travels have allowed me, as Eadweard and Percy promised, to see the country in a new way, to go beyond the standard-lens view of news and current affairs. It is a picture of Britain etc.

When I first arrived in Fleet Street in the early 1980s as a starry-eyed young radio journalist, my initiation began with a colleague leading me to the pub. It was barely opening time as we walked into the King and Keys. There, amid the smoky gloom, I was introduced to one of the newspaper world’s most celebrated figures, the editor of the Daily Telegraph , Bill Deedes. The great man sized me up. ‘You will have a malt whisky, dear boy,’ he said. I started to splutter something about how it was only eleven in the morning, but he quickly closed the discussion by adding, ‘a large one.’

It would be years before I fully understood the gesture: I was being blooded for an industry where alcohol was as much a part of the process as ink and paper. But it was also an indication of something apparently incredible: that Britain’s drink problems should not be blamed on drink.

In those days every Fleet Street title had its pub: the Telegraph occupied the King and Keys; the now defunct News of the World drank at ‘The Tip’ (The Tipperary); the Daily Express was resident at ‘The Poppins’ (The Popinjay); the Mirror pub was known as ‘The Stab In the Back’ (The White Hart). Drinking was ritual and tribal. Tales of drunken fights and indiscretions were sewn into the colourful tapestry of Grub Street legend, inebriated misadventures to be reverentially recounted and embellished. Pickled hacks could be found propping up many of the bars, victims treated with the respect of war veterans.

Newspaper people drank around the clock; magistrates had been persuaded to adjust local licensing hours so that city workers could enjoy a glass or two of ale at any time of the day or night. The social wreckage from alcohol was strewn all over Fleet Street — broken marriages, stunted careers and inflamed livers. The British press were pioneers of 24-hour opening and regarded themselves as experts on its potential consequences years before the 2001 General Election, when Tony Blair wooed young voters with a promise on a beer mat: ‘cdnt give a XXXX 4 lst ordrs? Vote labour on thrsdy 4 xtra time.’

Читать дальше