It was to get worse. Rationing in the Second World War saw the Ministry of Food stipulate that only one type could be manufactured — the National Cheese. A form of rubbery cheddar, this abomination came to define cheese in the nation’s mind. To this day there are many who still think of cheese as a lump of orange sweaty fat, grated onto a slice of white.

By the 1970s, bland, processed, homogenised factory-made gunk was routinely skewered on cocktail sticks and accompanied by a chunk of tinned pineapple, a pitiful display of what amounted to British gastronomic refinement. Our plates reflected an unshakeable faith in mass production and technological advance, the qualities that had spawned an empire two centuries before.

The country was pinning its hopes on arresting economic and industrial decline through the appliance of science. Food was predicted to become space-age rocket fuel. ‘Much of the food available will be based on protein substitutes,’ the presenters of BBC TV’s Tomorrow’s World promised, ‘delivered once a month in disposable vacuum packs.’ Meanwhile on ITV, the commercial break saw robotic aliens chortling at the suggestion that people might peel a potato rather than simply add water to freeze-dried powdered mash.

Despite all this, the big cheeses in the UK’s dairy industry were casting envious glances at our continental cousins with their fancy Brie and Camembert, products oozing with authenticity and sophistication. It was noted how British high-street shoppers were being sold symmetrical slices of globo-gloop in airtight plastic pouches while French fromageries offered consumers dozens of local artisanal cheeses, beautifully prepared and perfectly stored.

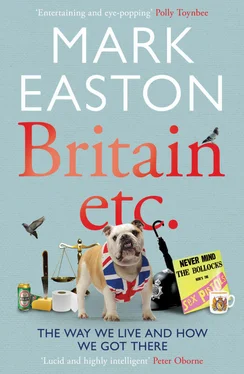

There was anxiety in the air. Membership of the European Economic Commuity (EEC) and the introduction of European-style decimalisation had led to disquiet over an apparent loss of British national identity. Some feared that obsession with an antiseptic future had led us to forget our rich heritage. In May 1982, at a dinner in Edinburgh for the French Prime Minister François Mitterrand, Margaret Thatcher quoted from a recently published book that had compared France and Britain and suggested it was no longer at all clear who has what, as nations copy each other so quickly. Her speech posed the question as to whether a nation’s essential genius will be lost in the process of unification. Mrs Thatcher thought not. ‘The nation of Racine, Voltaire, Debussy and Brie will persist,’ she concluded. ‘The nation of Shakespeare, Adam Smith, Elgar and Cheddar is also alive and strong.’

But within months the nation of Cheddar was attempting to copy the nation of Brie. It involved the forced marriage of cutting-edge science and traditional craft, the ceremony taking place in a shed in Shropshire. Following a two-year gestation at the cheese laboratory in Crudgington, on 27 September 1982, Lymeswold was born.

The cheese was the brainchild of Sir Stephen Roberts, an entrepreneurial farmer who ran the Milk Marketing Board. At the time, Britain’s dairy industry was tormented by what it regarded as unfair distribution of European agricultural subsidies. French farmers got the curds, it was felt, while the Brits were left with the whey. Sir Stephen decided to take the French on at their own game, and lab-coated food technicians were briefed to construct a new English soft cheese, with a white mould rind but without the runny, pungent characteristics of Camembert or Brie. These properties, it was felt, would give the product the broadest appeal. From Crudgington, he hoped, a cheese would emerge to restore British pride and mount a challenge to the global dairy market.

His invention needed a name — something that would evoke the tradition and local provenance of great English cheeses. Marketing experts tested many ideas, but the one which scored best in research was Wymeswold, the name of a small Leicestershire village that had been considered as a production site at one point. Trademark considerations ruled that one out. After further discussion, the cheese was christened Lymeswold.

It was a huge success. In the House of Commons, politicians hailed it as a potential boost to Britain’s balance of payments; the Agriculture Minister Peter Walker revealed that even his dog enjoyed the new cheese. Domestic demand was so great that there were soon shortages in the shops, but it was its popularity that would prove to be Lymeswold’s downfall. To foodies, the cheese reeked of slick marketing, its mask of authenticity as thin as its white rind; when under-matured stocks were released to increase supply, critics were happy to encourage a reputation for poor quality. Demand quickly fell off, and ten years after its launch, Lymeswold was quietly buried. Few mourned its passing.

These were, though, desperate days for Britain’s dairy farmers. The price of milk had plummeted so low it was impossible to make money from it. Resilience and imagination were all that stood between them and the collapse of their industry. What happened next is the uplifting story of how localism triumphed over centralised control; how the joyless yoke of homogenisation and industrialisation was lifted from the creativity and diversity of the British Isles. It was the moment when we realised that big wasn’t always beautiful, that new wasn’t always better than old, that science didn’t always trump art. It was the time when we rediscovered the true meaning of authenticity.

The sharp-suited marketing men spotted it first. ‘TREND: People are choosing authenticity as a backlash to aspects of modern life,’ one agency’s analysis reported. ‘TREND: Consumers are seeking to “reconnect with the real”.’ The food industry could almost taste the opportunity. Farmers were advised that products should have a ‘compelling brand narrative based on traditions, heritage and passion’.

Suddenly, everybody wanted authenticity liberally sprinkled on meatballs, melted on cauliflower and placed in great chunks between doorsteps of wholemeal. In the spring of 1997, amid the opulence of the luxury Lanesborough Hotel on London’s Hyde Park Corner, the British Cheese Board was launched to the world. A celebrity chef was on hand to remind people of the versatility of cheese, and a survey revealed that 98 per cent of the UK population enjoyed eating the stuff. It was a self-confident affair. Supermarkets began to talk about ‘provenance’, with agents scouring the country for products that would allow their customers to ‘reconnect with the real’. The European Union also announced a ‘renaissance of Atlantic food authenticity’ and bunged a bit of cash to British dairy farmers previously isolated by geography and indifference.

On the island of Anglesey, Margaret Davies was given EU help in turning milk from her 120 pedigree Friesian cows into Gorau Glas cheese. Humming with authenticity, Margaret’s soft blue-veined Welsh variety was soon selling at £27 a kilo, one of the most expensive cheeses in the world. In the Somerset village of Cricket St Thomas, farmers promoted their Capricorn Goats Cheese with pictures of the individual goats. Beryl, Eva, Flo, Ethel and Dot were allegedly responsible for what was described as ‘a noble and distinctive’ product. This wasn’t ordinary cheese, this was cheese crafted and ripened in the lush dairy pastures of a West Country valley. The man from Marks & Spencer was among the first supermarket reps to don his wellies and beat a path to the farmer’s door. Britain was rejecting the global and virtual in favour of the local and real. And reality meant getting your hands dirty and your feet wet. One brand consultancy told prospective clients: ‘Imperfection carries a story in a way that perfection can only dream about.’

The affluent middle classes entered the new millennium demanding real ale, slow food, organic turnips and unbranded vintage fashion. They went to Glastonbury to dance in primeval mud, stopping off at the deli on the way home for a sourdough loaf, a bag of Egremont Russets and a chunk of dairy heritage. Urban chic sported clods of rural earth as farmers’ markets and organic boxes headed to town. Localism became the mantra of politicians, bankers and grocers. From off-the-peg to bespoke, Britain lost confidence in corporate giants and turned to the little guy. Searching for distinctiveness and individuality, the country eschewed the globalising instincts associated with empire, peering further back in our history for an answer to the identity crisis of the twenty-first century.

Читать дальше