Vladimir Nabokov - Speak, Memory

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Vladimir Nabokov - Speak, Memory» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Vintage International, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Speak, Memory

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage International

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-307-78773-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Speak, Memory: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Speak, Memory»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Conclusive Evidence

Lolita

Pnin

Despair

The Gift

The Real Life of Sebastian Knight

The Defense

Speak, Memory — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Speak, Memory», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A recent visit to the Public Library in New York has revealed that the above incident does not appear in my father’s book Iz Voyuyushchey Anglii , Petrograd, 1916 ( A Report on England at War )—and indeed there are not many samples therein of his habitual humor beyond, perhaps, a description of a game of badminton (or was it fives?) that he had with H. G. Wells, and an amusing account of a visit to some first-line trenches in Flanders, where hospitality went so far as to allow the explosion of a German grenade within a few feet of the visitors. Before publication in book form, this report appeared serially in a Russian daily. There, with a certain old-world naïveté, my father had mentioned making a present of his Swan fountain pen to Admiral Jellicoe, who at table had borrowed it to autograph a menu card and had praised its fluent and suave nib. This unfortunate disclosure of the pen’s make was promptly echoed in the London papers by a Mabie, Todd and Co., Ltd., advertisement, which quoted a translation of the passage and depicted my father handing the firm’s product to the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, under the chaotic sky of a sea battle.

But now there were no banquets, no speeches, and even no fives with Wells whom it proved impossible to convince that Bolshevism was but an especially brutal and thorough form of barbaric oppression—in itself as old as the desert sands—and not at all the attractively new revolutionary experiment that so many foreign observers took it to be. After several expensive months in a rented house in Elm Park Gardens, my parents and the three younger children left London for Berlin (where, until his death in March, 1922, my father joined Iosif Hessen, a fellow member of the People’s Freedom Party, in editing a Russian émigré newspaper), while my brother and I went to Cambridge—he to Christ College, I to Trinity.

2

I had two brothers, Sergey and Kirill. Kirill, the youngest child (1911–1964), was also my godson as happened in Russian families. At a certain stage of the baptismal ceremony, in our Vyra drawing room, I held him gingerly before handing him to his godmother, Ekaterina Dmitrievna Danzas (my father’s first cousin and a grandniece of Colonel K. K. Danzas, Pushkin’s second in his fatal duel). In his childhood Kirill belonged, with my two sisters, to the remote nurseries which were so distinctly separated from his elder brothers’ apartments in town house and manor. I saw very little of him during my two decades of European expatriation, 1919–1940, and nothing at all after that, until my next visit to Europe, in 1960, when a brief period of very friendly and joyful meetings ensued.

Kirill went to school in London, Berlin and Prague, and to college at Louvain. He married Gilberte Barbanson, a Belgian girl, ran (humorously but not unsuccessfully) a travel agency in Brussels, and died of a heart attack in Munich.

He loved seaside resorts and rich food. He loathed, as much as I do, bullfighting. He spoke five languages. He was a dedicated practical joker. His one great reality in life was literature, especially Russian poetry. His own verse reflects the influence of Gumilyov and Hodasevich. He published sparsely and was always as reticent about his writing as he was about his persiflage-misted inner existence.

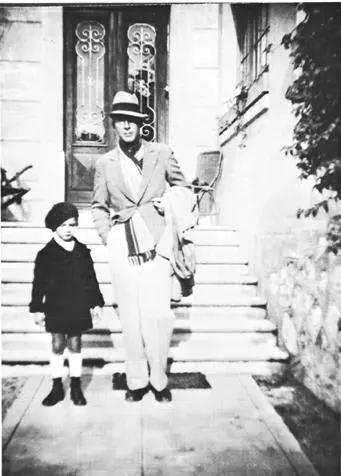

A snapshot taken by my wife of our three-year-old son Dmitri (born May 10, 1934) standing with me in front of our boardinghouse, Les Hesperides, in Mentone, at the beginning of December 1937. We looked it up twenty-two years later. Nothing had changed, except the management and the porch furniture. There is always, of course, the natural thrill of retrieved time; beyond that, however, I get no special kick out of revisiting old émigré haunts in those incidental countries. The winter mosquitoes, I remember, were terrible. Hardly had I extinguished the light in my room than it would come, that ominous whine whose unhurried, doleful, and wary rhythm contrasted so oddly with the actual mad speed of the satanic insect’s gyrations. One waited for the touch in the dark, one freed a cautious arm from under the bedclothes—and mightily slapped one’s own ear, whose sudden hum mingled with that of the receding mosquito. But then, next morning, how eagerly one reached for a butterfly net upon locating one’s replete tormentor—a thick dark little bar on the white of the ceiling!

For various reasons I find it inordinately hard to speak about my other brother. That twisted quest for Sebastian Knight (1940), with its gloriettes and self-mate combinations, is really nothing in comparison to the task I balked in the first version of this memoir and am faced with now. Except for the two or three poor little adventures I have sketched in earlier chapters, his boyhood and mine seldom mingled. He is a mere shadow in the background of my richest and most detailed recollections. I was the coddled one; he, the witness of coddling. Born, caesareanally, ten and a half months after me, on March 12, 1900, he matured earlier than I and physically looked older. We seldom played together, he was indifferent to most of the things I was fond of—toy trains, toy pistols, Red Indians, Red Admirables. At six or seven he developed a passionate adulation, condoned by Mademoiselle, for Napoleon and took a little bronze bust of him to bed. As a child, I was rowdy, adventurous and something of a bully. He was quiet and listless, and spent much more time with our mentors than I. At ten, began his interest in music, and thenceforth he took innumerable lessons, went to concerts with our father, and spent hours on end playing snatches of operas, on an upstairs piano well within earshot. I would creep up behind and prod him in the ribs—a miserable memory.

We attended different schools; he went to my father’s former gimnasiya and wore the regulation black uniform to which, at fifteen, he added an illegal touch: mouse-gray spats. About that time, a page from his diary that I found on his desk and read, and in stupid wonder showed to my tutor, who promptly showed it to my father, abruptly provided a retroactive clarification of certain oddities of behavior on his part.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Speak, Memory»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Speak, Memory» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Speak, Memory» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.