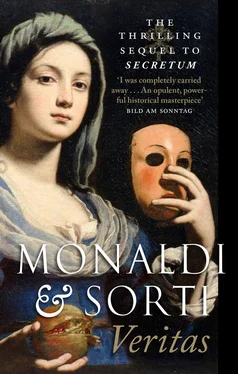

Rita Monaldi - Veritas

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rita Monaldi - Veritas» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Veritas

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Veritas: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Veritas»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Veritas — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Veritas», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And so began a new life for my family and myself in the Most August Caesarean capital, where even the humblest houses, as Cardinal Piccolomini had noted with astonishment, resembled princely palaces, and where every day the gates of the massive and sublime city walls let through an unending stream of provisions: carts loaded with eggs, crayfish, flour, meat, fish, countless birds, over three hundred wagons laden with casks of wine; by evening it would all be gone. Cloridia and I gazed open-mouthed at the greedy rabble, devoted to its belly, which every Sunday consumed what at Rome it would take us a year to earn. We ourselves were now allowed a place at the table of this lavish and eternal banquet.

Atto Melani’s act of generosity had come about thanks to a fortunate conjunction of circumstances: His Caesarean Majesty Emperor Joseph I wished to restore an ancient building that stood at the gates of Vienna, and needed a master chimney-sweep who would undertake to renovate the flues and overhaul the system of protection against fires, which seemed to be breaking out with increasing frequency. Shortly after my appointment, however, there had been such abundant snowfalls that I had been unable to start my work there, and, to make matters worse, part of the building had fallen in, making building repairs necessary. Today I was to visit the Caesarean property for the first time.

Just one thing was still unclear to me: why had the Emperor not appointed one of the many other master chimney-sweeps of the court, who were already responsible for the numerous royal residences?

Abbot Melani had even arranged for a small single-storey house to be purchased in our name near the church of St Michael in the Josephina, and had undertaken to have an extra storey added, an operation that was still under way: my family and I would soon enjoy the great luxury of having a house all to ourselves, with the ground floor given over to business and the upper one to our living quarters. A real dream for us, after our experience in Rome of having to share a tufo cellar with another family of paupers. .

Now we could even send large sums of money to our two daughters who were still there, and we were even planning to have them join us in Vienna as soon as our new house was ready.

Atto, in his donation, had also included wages for a tutor who would teach our child to read and write in Italian, “since,” he had written in the accompanying letter, “Italian is an international language and is, indeed, the official language of the Caesarean court, where hardly any other is spoken. The Emperor, like his father and his grandfather before him, attends Italian sermons, and the cavaliers of these lands have such an affinity for our nation, that they vie for the opportunity to travel to Rome and master our language. And those who know it enjoy great esteem throughout the Empire and have no need to learn the local idioms.”

I was infinitely grateful to Melani for what he had done, even though I had been a little hurt to find no personal note in his letter, no news of himself, no expressions of affection, just generic salutations. But perhaps, I thought, the letter had been drawn up for him by a secretary, Atto being too old and probably too sick to see to such details.

For my part I had, of course, written a letter warmly proclaiming my sense of obligation and affection. And even Cloridia, having overcome her age-old mistrust of Atto, had sent him lines of sincere gratitude together with an elegant piece of crochet work, to which she had applied herself for weeks: a warm, soft shawl in camlet of Flanders, yellow and red, the Abbot’s favourite colours, with his initials embroidered on it.

We had received no reply to our attestations, but this did not surprise us, given his advanced age.

Our little boy was now doing his best to copy into his notebook simple phrases in the Germanic idiom and in a special gothic cursive, very difficult to read, which the people here call Current.

While it was true, as Abbot Melani said, that Italian was the court language in Vienna — indeed, the sovereigns who wrote to the Emperor were required to do so in that language — the common people were much more at ease in German; for a chimney-sweep wishing to practise his trade, it was essential to learn its rudiments at least.

With this in mind, I had decided that the wages Atto had set aside for an Italian tutor should be used to pay a teacher of the local language, since I myself would undertake to instruct my son in his native language, as I had already done, quite successfully, with his two sisters. And so every second evening, Cloridia, my son and I received a visit from this teacher, who would endeavour for a couple of hours to illuminate our poor minds on the intricate and impenetrable universe of the Teutonic language. Cardinal Piccolomini had already complained of its immeasurable difficulties and its almost total incompatibility with other idioms, and this had been proved since the days of Giovanni da Capistrano; during his visit to Vienna, he had delivered his sermons against the Turks from the pulpit in the Carmelite Square in Latin; he had then been followed by an interpreter, who took three hours to repeat everything in German.

While our little infant made great strides, my wife and I were left floundering. We made greater progress, fortunately, in reading, and that was why, as I said earlier, that in the late morning of 9th April of the year 1711, in the brief post-prandial pause, I was able to flick casually (almost) through the New Calendar-Agenda of Krakow, written by Matthias Gentille, Count Rodari of Trent, while my little boy doodled at my feet until it should be time to go back to work with me.

Like every master chimney-sweep of Vienna, I too had my Lehrjunge , or apprentice, and he was, of course, my son, who at the age of eight had already endured — but also learned — more than a boy twice his age.

A little while later Cloridia joined us.

“Come quickly, they’re about to turn into the street. And then I have to get back to the palace.”

Thanks to the good offices of the Chormaisterin of the convent, my wife had found a highly respectable job at just a short distance from the religious house. In Porta Coeli Street, or Himmelpfortgasse as the Viennese say, there was a building of great importance: the winter palace of the Most Serene Prince Eugene of Savoy, President of the Imperial Council of War, great condottiero in the service of the Empire in the war against France, as well as victor over the Turks. And now, on that very day, there was to be an extremely important event at the palace: at midday an Ottoman embassy was expected to arrive from Constantinople. A great opportunity for my wife, born in Rome, but from the womb of a Turkish mother, a poor slave who had ended up in enemy hands.

Two days earlier, on Tuesday, five boats had arrived at the Leopoldine Island in Vienna, on the branch of the Danube nearest the ramparts, and the Turkish Agha, Cefulah Capichi Pasha, had disembarked with a retinue of about twenty people. Suitable lodgings had been provided for them on the island. To tell the truth, it was not entirely clear just what the Ambassador of the Sublime Porte had come to do in Vienna.

There had been peace with the Ottomans for several years now, since 11th September 1697, when Prince Eugene had thoroughly defeated them at the Battle of Zenta and forced them to accept the subsequent Peace of Karlowitz. War was now raging, not with the Infidel but with Catholic France over the question of the Spanish throne; relations with the Porte, usually so troubled, seemed to be tranquil. Even in restless Hungary, where the imperial armies had fought for centuries against the armies of Mahomet, the princes who had rebelled against the Emperor, usually chafing and combative, seemed to have been finally tamed by our beloved Joseph I, who was not known as “the Victorious” for nothing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Veritas»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Veritas» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Veritas» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.