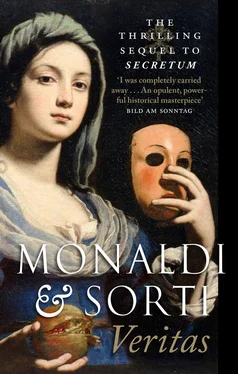

Rita Monaldi - Veritas

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rita Monaldi - Veritas» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Veritas

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Veritas: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Veritas»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Veritas — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Veritas», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“And nothing to eat but light soup for two weeks,” concluded the Chormaisterin, looking closely at the child.

“I knew it. The usual generosity. .”

Cloridia’s harsh and unexpected outburst made me flush with embarrassment; I was afraid we would soon be driven out, but the victim reacted with an amused laugh.

“I see that you know us well,” she answered, not in the least offended. “But I guarantee that in this case my fellow sisters’ proverbial stinginess has nothing to do with it. Spelt soup with crushed prune stones cures all fluxions of the chest.”

“You treat people with spelt too,” remarked Cloridia in a dull voice after a moment’s silence. “So did my mother.”

“And so we have been doing ever since the early days of our holy sister Hildegard, Abbess of Bingen,” Camilla declared with a sweet smile. “But I’m pleased to hear that your mother appreciated it too; one day, if you feel like it, will you tell me about her?”

Cloridia responded with hostile silence.

She was truly amiable, Camilla de’ Rossi, I thought, despite my wife’s diffidence. She was dressed in a white habit, its sleeves lined with fine, pure Indian linen, and a hood in the same linen with a black crépon veil hanging down behind.

The face that the hood and veil left uncovered belonged to neither of the two physiognomies peculiar to young nuns (or secular sisters, it made little difference): she had neither the watery, dull eyes surrounded by pudgy pink and white cheeks like ham lard, nor the hard little tetchy eyes set in a sallow, scraggy complexion. Camilla de’ Rossi was an attractive, blooming girl, whose dark, proud eyes and lively mouth reminded me of my wife’s features just a few years earlier.

There was another knock.

“Your lunch has arrived,” announced the Chormaisterin, as she opened the door to two scullery maids carrying trays.

The meal, curiously, was all based on spelt: flat loaves of spelt and chestnuts, cream of apples and spelt, a pie of spelt grains and fennel.

“Now hurry up,” urged Camilla after we had refreshed ourselves, “you’re expected in half an hour’s time at the notary.”

“So you know. .” I said, astonished.

“I know everything,” she cut me short. “I’ve already sent word to the notary that you’ve arrived. So come along; I’ll look after your boy.”

“You don’t really expect me to leave my son in your hands?” protested Cloridia.

“We are all in the hands of Our Lord, my daughter,” answered the Chormaisterin maternally, though as to age she could have been our daughter.

Having said this, she ushered us with gentle firmness towards the door.

I pleaded to Cloridia with my eyes not to offer any resistance nor to make any of her less gracious remarks about the tribe of the brides of Christ.

“Anything, if it means I don’t see soot again,” she merely said.

I thanked God that my consort, thanks to her hatred of the chimney-sweeping trade, had finally given in. And perhaps the young nun, who seemed to have genuinely taken our little boy’s health to heart, was beginning to break down Cloridia’s wall of diffidence.

When we stepped outside we found the convent’s idiot leaning against the wall and waiting for us; the Chormaisterin gave him a quick confirmatory glance.

“This is Simonis. He’ll take you to the notary.”

“But Mother,” I tried to object, “I don’t know German very well, and I don’t understand when he speaks to me. When we got here. .”

“What you heard wasn’t German: Simonis is Greek. And when he wants he can make himself understood, trust me,” she said with a smile, and without another word she closed the door behind us.

“Very generous this donation of Abbot Milani, yes, yes?”

It was with these words, spoken in diligent Italian with only Melani’s name pronounced incorrectly, that the notary welcomed us into his office, gazing at us from behind his little spectacles; unfortunately it was not clear whether the words constituted an affirmation or a question.

We had arrived at the office after a short walk through the snow, during which our limbs had nonetheless grown exceedingly numb. The terrible winter of 1709, which had brought our family and the whole of Rome to its knees, had been nothing in comparison with this, and I realised that the heavy overcoats we had bought before our departure were as much protection as an onion skin. Cloridia was tormented by her fluxion of the chest.

“Yes, yes,” the notary repeated several times, after bidding us remove our coats and shoes and inviting us to sit down opposite him. Simonis had remained in the anteroom.

While we enjoyed the warmth of an enormous and rich cast-iron stove coated with majolica, such as I had never seen before, he began to leaf through a file, whose cover bore words in gothic characters.

Cloridia and I, our chests bursting with silent tension, looked on as his hands riffled through the papers. My poor wife lifted a hand to her temple: I realised she was suffering one of those terrible headaches that had tortured her ever since we had fallen into poverty. What news did those papers hold? Was the end of our troubles inscribed there, or was it all just another hoax? I could feel my belly churning with anxiety.

“The documents are all here: Geburtsurkunde, Kaufkontrakt and, above all, the Hofbefreyung ,” said the notary at last, in a mixture of Italian and German. “Check the accuracy of the data,” he added, placing the documents before me, although I had by no means grasped their nature: “Signor Abbot Milani, your benefactor. .”

“Melani,” I corrected him, aware that Atto’s signature could give rise to similar misunderstandings.

“Ah, yes,” he said, after examining a page carefully. “As I was saying, Signor Abbot Melani and his procurators have been very diligent and precise. But the imperial court is very strict: if anything is wrong, there is no hope.”

“The imperial court?” I asked, full of hope.

“If the court doesn’t accept it, the donation cannot take effect,” the notary continued. “But now read this Geburtsurkunde carefully and tell me if all is in order.”

Having said this, he placed before me the first of four documents, which — to my no small surprise — proved to be a birth certificate bearing my name, specifying the day, month, year and place of my birth, as well as my paternity and maternity. This was truly singular, given that I was a foundling, and not even I knew when, where or to whom I had been born.

“This, then, is the Gesellenbrief,” insisted our interlocutor, who, after gazing out of the window, suddenly seemed to be in a great hurry. “I repeat, the court is very strict. Especially when it comes to the question of apprenticeship; otherwise the confraternity could create problems for you.”

“The confraternity?” I asked, not having the foggiest idea what he was talking about.

“Now let’s proceed, since there is little time. You can ask your questions later.”

I would have liked to say that I still had not understood what purpose all those documents (false ones, to boot) served. Above all, the notary’s words did not explain what Atto Melani’s donation consisted of. Nonetheless, I obeyed and refrained from commenting. Cloridia kept quiet too, her eyes glazed by the migraine and her fluxion of the chest.

“The Hofbefreyung, to tell the truth, is less urgent: I’m here to guarantee its validity. Since time is short, you could look it over in the carriage.”

“In the carriage?” said Cloridia in surprise. “Where to?”

“To check that what is contained in the Kaufkontrakt is correct, where else?” he answered, as if stating the obvious, and he got to his feet, beckoning us to follow him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Veritas»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Veritas» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Veritas» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.