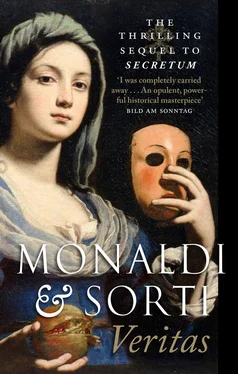

Rita Monaldi - Veritas

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Rita Monaldi - Veritas» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Veritas

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Veritas: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Veritas»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Veritas — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Veritas», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On the catafalque hangs a funeral drape of black velvet with silver fringes, on which is embroidered in golden characters:

Hic iacet

Abbas Atto Melani Pistoriensis in Etruria,

Pietate erga Deum

Obsequio erga Regem

Illustris

Ω. Die 4. Ianuarii 1714. Ætatis suæ octuagesimo octavo

Patruo Dilectissimo

Dominicus Melani nepos mestissimus posuit

The same words will be engraved on the sepulchral monument that Atto’s nephew has already commissioned from the Florentine sculptor Rastrelli. The Augustinian Fathers have granted the site in a side chapel close to the high altar, opposite the sacristy door. Atto will therefore be buried here, as he wished, in the same church where lie the mortal remains of another Tuscan musician: the great Giovan Battista Lulli.

“ Pietate erga Deum / Obsequio erga Regem / Illustris ”: the words are repeated on the two side columns, only the nearer of which I had been able to read before. “Illustrious for his devotion to God and his obedience to the King”: in reality, the former virtue is in conflict with the latter, and no one knows this better than I.

The orchestra begins the funeral mass. Wecrato singing:

Crucifixus et sepultus est

“Crucified and buried,” intones his reedy voice. I can make out nothing else, everything flickers and wavers around me: the faces, colours and lights blur like a painting that has fallen into water.

Atto Melani is dead. He died here, in Paris, in rue Plastrière, in the parish of Saint Eustache, the day before yesterday, 4th January 1714, at two in the morning. I was with him.

“Stay with me,” he said, and breathed his last.

I will stay with you, Signor Atto: we made a pact, I made you a promise, and I intend to abide by it.

It matters not how many times you broke our pacts, how many times you lied to the twenty-year-old boy servant and then to the father and family man. This time there will be no surprises for me: you have already fulfilled your obligation towards me.

Now that I am almost the same age that you were when we first met, now that your memories are mine, that your old passions are flaring up in my breast, your life is my life.

It was thanks to a journey that I found you again, three years ago, and now another one, the supreme journey of death, is bearing you away to other shores.

Safe journey, Signor Atto. You will get what you asked of me.

Rome

JANUARY 1711

“Vienna? And why on earth should we go to Vienna?” My wife Cloridia stared at me wide-eyed with surprise.

“My dear, you grew up in Holland, you had a Turkish mother, you came here to Rome all by yourself when you weren’t even twenty, and now you’re scared of a little trip to the Empire? What am I supposed to say, seeing that I’ve never been beyond Perugia?”

“You’re not telling me we’re going to make a trip to Vienna; you’re telling me we should go and live there! Do you happen to know any German?”

“Well, no. . not yet.”

“Give it to me,” she said, and she irritably snatched the document from my hand.

She read it through again for the umpteenth time.

“And just what is this donation? A piece of land? A shop? A job as a court servant? It doesn’t explain anything!”

“You heard the notary, just as I did: we’ll find out when we get there, but it’s certainly something of great value.”

“Right. We’ll go all the way there, clambering over the Alps, and then perhaps we’ll find it’s just another trick played by that scoundrel your Abbot, who’ll exploit you for some other crazy adventure and then throw you away like an old rag, leaving you penniless into the bargain!”

“Cloridia, think for a moment: Atto is eighty-five years old. What crazy adventures do you think he’s likely to embark on now? For a long time I thought he was dead. It’s quite something that he’s actually hired a notary to pay off his old debt to me. He must feel the end approaching and now he wants to set his conscience at rest. In fact, we should be thanking God for granting us such an opportunity when things are so hard for us.”

My wife lowered her eyes.

For two years things had been bad, extremely bad, for us. The winter of 1709 had been very severe, with endless snow and ice. This had led to a bitter famine, which, together with the ruinous war that had been dragging on for seven years over the Spanish throne, had thrown the Roman people into dire poverty. My family and I, with the new addition of a six-year-old son, had not been spared this fate: a year of bad weather and frosts, something never seen before in Rome, had made our smallholding unproductive and wiped out my prospects on the land. The decline of the Spada family and the consequent abandonment of the villa at Porta San Pancrazio, where I had undertaken many profitable little jobs over the years, had made our situation even worse. My wife’s efforts to halt our financial ruin through the art of midwifery had, alas, proved insufficient, even though she had been practising it for decades to great acclaim, and now had the help of our two daughters, aged twenty-three and nineteen. The famine had also increased the number of new mothers who were penniless, and my wife assisted these with the same self-denying spirit with which she attended to the noblewomen.

And so the list of our debts increased and in the end, in order to survive, we were forced to take the most painful step: the sale, in favour of the moneylenders of the ghetto, of our small house and holding, bought twenty-six years earlier with the little nest egg left us by my father-in-law of blessed memory. We found shelter in the city, taking lodgings in a basement that we had to share with a family from Istria; at least it had the advantage of not being too damp and maintaining a fairly constant temperature in winter, even in the hardest frost, thanks to the fact that it had been dug into the tufo.

In the evening we ate black bread and broth with nettles and grass. And in the day we got by on acorns and other berries that we scraped together and ground up to make a kind of loaf, garnishing it with little turnips. Shoes soon became a luxury and gave way, even in winter, to wooden clogs and slippers stitched together at home from old rags and hemp-twine.

I could find no work, none at least worthy of the name. My slight build often counted against me, for example in any job that involved lifting or carrying. And so in the end I had been reduced to taking on the vilest and most sordid of jobs, one that no Roman would ever dream of accepting, but the only one in which I had an advantage over family breadwinners of greater stature: a chimney-sweep.

I was an exception: chimney-sweeps and roof tilers usually came from the Alpine valleys, from Lake Como, Lake Maggiore, from the Valcamonica, the Val Brembana and also from Piedmont. In these poor areas the great hunger forced families to give up children as young as six or seven seasonally to the chimney-sweeps, who made use of them to clean — at the risk of their lives — the narrower flues.

Having the build of a child but the strength of an adult, I could offer the best guarantee that the job would be done properly: I would screw myself into the narrow openings and clamber up agilely through the soot, but I would also scrape the black walls of the hood and flue with greater skill than any child could apply to the job. Furthermore, the fact that I was so light saved the tiles from damage when I climbed onto the roof to clean or adjust the chimney pot, and at the same time there was no risk of my dashing my brains out on the ground, as happened all too often to the very young chimney-sweeps.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Veritas»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Veritas» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Veritas» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.