Robert Wilson

A Small Death in Lisbon

Copyright © Robert Wilson 1999

I'd like to thank Michael Biberstein for correcting my German and Ana Nobre de Gusmão for checking all things Portuguese. Any errors that remain are of my own making.

Over the years a lot of people have talked to me, and contributed with information, insight and books. I'd like particularly to thank the following: Mizette Nielsen, Paul Mollet, Alexandra Monteiro, Natalie Reynolds, Elwin Taylor and Nick Ricketts.

This book took some research and the staff of The Bodleian in Oxford, A Biblioteca/Museu 'República e Resistência', A Biblioteca de Estudos Olisiponenses and A Biblioteca Nacional in Lisbon, were always helpful.

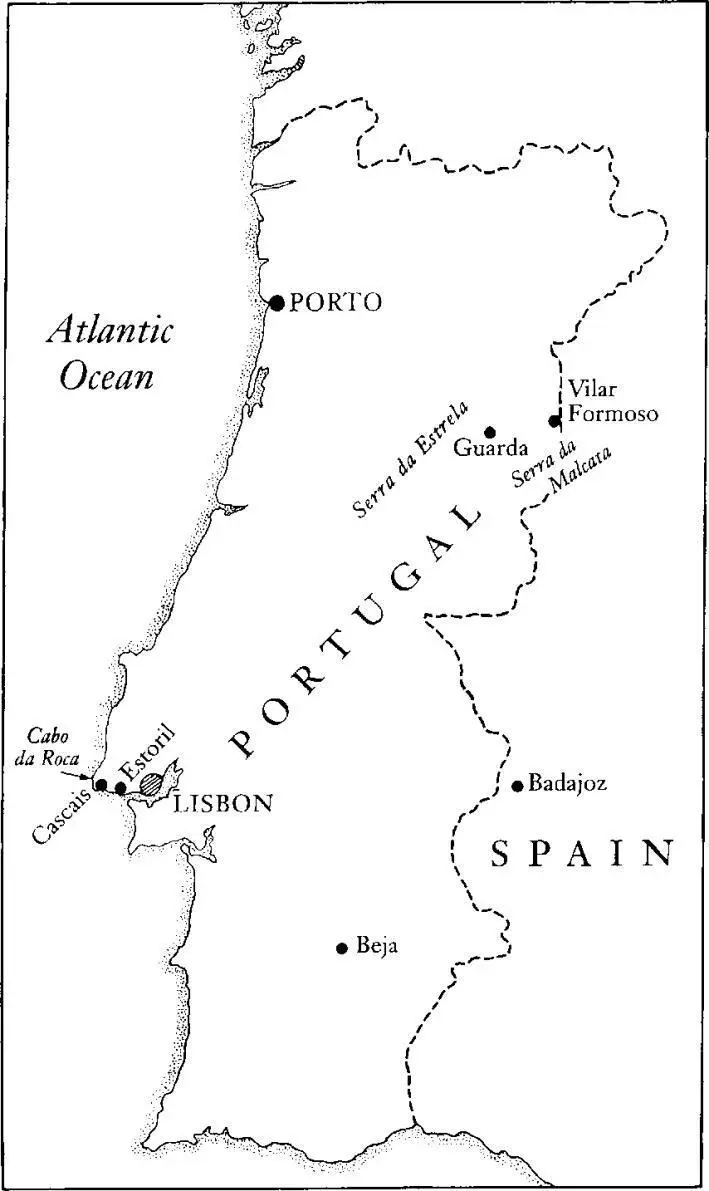

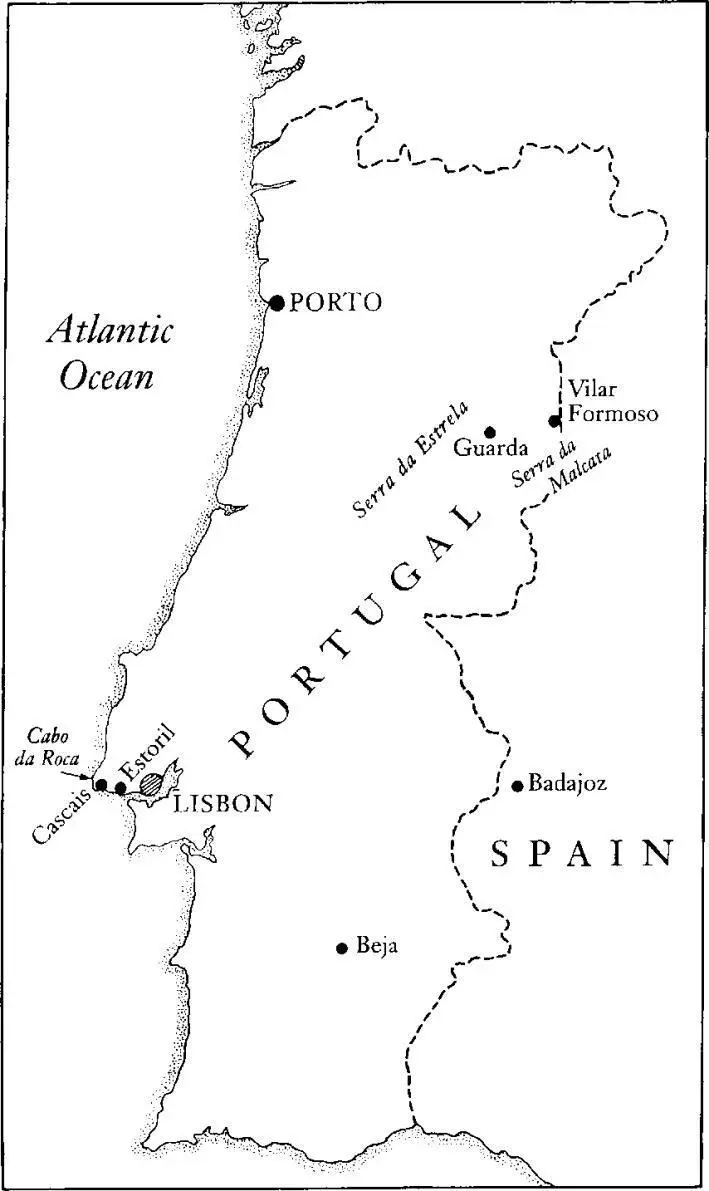

I also visited the Beira and the following were particularly friendly and helpful: R. A. Naique, Director Geral of Beralt Tin & Wolfram, Fernando Pàolouro of the Journal do Fundào, José Lopes Nunes and Councillor Francisco Abreu of Penamacor. In addition I would like to thank the people of Fundào, Penamacor, Sabugeiro, Sortelha, and Barco for their help and memories. I would also like to thank Manuel Quintas and the staff of the Hotel Palácio in Estoril.

Finally, although this book is dedicated to her, that does not do justice to my wife's contribution to the work. She was tireless in discussing with me the form of the book, she put in days of research in Oxford and Lisbon, she gave me total support and encouragement through the long months of writing and she was a dedicated and intelligent editor. This would have been a doubly hard task without you. Thank you.

She was lying on a crust of pine needles, looking at the sun through the branches, beyond the splayed cones, through the nodding fronds. Yes, yes, yes. She was thinking of another time, another place when she'd had the smell of pine in her head, the sharpness of resin in her nostrils. There'd been sand underfoot and the sea somewhere over there, not far beyond the shell she'd held to her ear listening to the roar and thump of the waves. She was doing something she'd learned to do years ago. Forgetting. Wiping clean. Rewriting little paragraphs of personal history. Painting a different picture of the last half-hour, from the moment she'd turned and smiled to the question: 'Can you tell me how…?' It wasn't easy, this forgetting business. No sooner had she forgotten one thing, rewritten it in her own hand, than along came something else that needed reworking. All this leading to the one thing that she didn't like roaming loose around her head, that she was forgetting who she was. But this time, as soon as she'd thought the ugly thought, she knew that it was better for her to live in the present moment, to only move forward from the present in millimetre moments. 'The pine needles are fossilizing in the backs of my thighs,' was as far as she got in present moments. A light breeze reminded her that she'd lost her pants. Her breast hurt where it was trapped under her bra. A thought tugged at her. 'He'll come back. He's seen it in my face. He's seen it in my face that I know him.' And she did know him but she couldn't place him, couldn't name him. She rolled on to her side and smiled at what sounded like breakfast cereal receiving milk. She knelt and gripped the rough bark of the pine tree with the blunt ends of her fingers, the nails bitten to the quick, one with a thin line of drying blood. She brushed the pine needles out of her straight blonde hair and heard the steps, the heavy steps. Boots on frosted grass? No. Move yourself. She couldn't get the panic to move herself. She'd never been able to get the panic to move herself. A flash as fast as a yard of celluloid ripped through her head and she saw a little blonde girl sitting on the stairs, crying and peeing her pants because he'd chased her and she couldn't stand to be chased. The rush. The gust of terrible energy. The wind up the stairs, whistling under the door. The forces winding up to deliver. Doors banging far off in the house. The thud. The thud of a watermelon dropped on tiles. Split skin. Pink flesh. Her blonde hair reddened. The cranial crack opened up. The bark bit a corner of her forehead. Her big blue eye saw into the black canyon.

Friday, 12th June 199-, Paço de Arcos, near Lisbon

'Ladies and gentlemen,' said the mayor of Paço de Arcos, 'may I present to you Inspector José Afonso Coelho.'

It had been a hot day with a perfect blue sky and now a soft lick of a breeze was coming off the ocean to mess with the poplars and pepper trees in the public gardens. The faded pink disused cinema's walls drank in the evening light, a small girl squealed, rocking on a happy dinosaur, a big man smoked and sucked beer next to her, women greeted each other with kisses, their dresses rippled in the cool. Cars flashed past on the Marginal, a light aeroplane sputtered out to sea over the sand bank. The air was redolent of grilled sardines and a bureaucrat had a microphone.

'Zé Coelho,' said the mayor, using my more recognized name, but still not squeezing out much more interest from the festa de Santo António crowd which included my sixteen-year-old daughter, Olivia, my sister and brother-in-law and four of their seven children.

The mayor talked on, elaborately explaining the event in rococo Portuguese to a robustly inattentive public consisting mostly of my neighbours, who were well apprised of the bare facts which were: my wife died a year ago, I put on weight, to encourage me to take it off my daughter arranged this charity event with money pledged against each kilo lost and if I was a single gram over eighty kilos I was to have my perfect, neatly-clipped beard of twenty years shaved off in front of this rabble.

My daughter waved at me, my brother-in-law gave me a thumbs-up. I weighed in that morning at seventy-eight kilos, my stomach hadn't been as hard and flat since I was eighteen and I'd been cycling 250 kilometres a week with the police trainer. I was feeling supremely confident… until the mayor had started talking. There was something mannered about the crowd's insouciance, something insincere about my brother-in-law's encouragement, even my daughter's wave. I had a part to play, I knew it at that moment.

A fat man, balding with a heavy moustache, wearing a blazer, grey slacks and a wild tie arrived at my daughter's table. He kissed her on both cheeks and squeezed her shoulder. One of my nieces made room for him and after shaking everybody's hands he sat down.

There was a sudden silence. The mayor had arrived at the money. There was respect for the money.

'Two million, eight hundred and forty-three thousand, nine hundred and eighty escudos.'

The crowd went up like a flight of fantails. That… even I had to agree, was a hell of a lot of money for seventeen kilos of lard. I held up my hand and took the applause like a returning monarch.

The band on the stand behind me cut in on my dignity and played a jaunty little number as if I was a toureiro who'd just executed a blinding move against the bull, and a group of small girls in traditional costume broke out into disorganized, elephantine dancing. Two local fishermen lifted a set of scales up on to the platform. The crowd left their seats by the bar and rushed the stage. The fat man sitting next to my daughter had his pen out and was writing. The mayor was fighting people off who wanted a go with the microphone which he'd stuffed inside his suit and the speakers were carrying the crunching explosions from his armpit.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу