If in 2002 Congress had committed to wartime tax surcharges, that is to say, it actualized the “we will pay” that Bush spoke of in his 2002 State of the Union Address, then it would have sent a powerful message both home and abroad. The American people would have heard that both the president and the Congress perceived the threat that Saddam Hussein posed to vital US interests as serious and grave. This clear, powerful message would also have been heard loud and clear overseas. Allies would be reassured that the United States had real evidence that security was threatened and enemies would know that it meant business. Bush’s claim that Hussein was evil and was propagating WMD would have become a costly, and therefore, a harder, message to send. That would have made for greater caution in sending it and greater believability if it were sent. Hussein would have known that Bush was serious. He might have agreed to even more access for weapons inspectors. He might also have contemplated fleeing into exile. And the United States might have saved $1 trillion and thousands of lives.

Once the material and human costs of war, and how they are to be paid for, is well publicized, these costs provide a performance standard against which to measure presidents. Once the people have such estimates they can decide whether they should get behind the president’s plan or protest against it. In a recent Internet-based experiment, political scientists Gustavo A. Flores-Macías and Sarah Kreps assessed the impact of taxation on support for a war. They asked voters about their support for a hypothetical war based on how the war is financed. They found that if a tax on war accompanies the proposed conflict, then there is on average 10 percent less support for the conflict than if it is to be financed through existing means and debt.14 Create that risk for presidents and they will be more thoughtful about the wars we fight. There are, after all, other ways to settle disputes.

When the costs are reasonably well anticipated by the people, the people provide a natural brake on the proclivity of politicians to fight. Instead, leaders must find peaceful means to fulfill their goals. Although paying to acquire land now appears out of fashion, it is worth noting that negotiated purchases followed by settlement expanded US lands to a far greater degree than war. Further, it did so at far lower cost. The Louisiana Purchase increased the United States by 828,000 square miles at a cost of about $15 million (a little more than a quarter-billion dollars today, adjusting for inflation). The incorporation of the enormous Oregon Territory was achieved through treaty negotiations with the British in 1818 and 1846 without a resort to arms. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that concluded the Mexican-American War gained 525,000 square miles for the United States in exchange for $18.25 million to Mexico (and to take on Mexican debt liabilities). However, the war cost $71 million to fight. Negotiation and paying for land proved much cheaper than fighting. War should be a last resort, only to be used when vital national interests are at stake. Unfortunately the people provide little retardant to fighting if they bear no costs. If plans such as ours are implemented, the burden of war will be transparently shifted to politicians who will naturally be induced to be more careful in their decisions to resort to force.

A Closing Observation

IMAGINE THAT WE ASSESSED THE QUALITY OF EACH PRESIDENT’S TERM IN office by how much the nation enjoyed peace and prosperity. It seems uncontroversial that periods of peace—when few Americans die in war—and periods of prosperity—when the average American’s income grows rapidly from year to year—are the gold standard we all seek in our leaders. Yet if we evaluated presidents based on how the nation did on those two standards during their time in office, we would come up with a radically different view of who the great presidents were from those we currently laud.

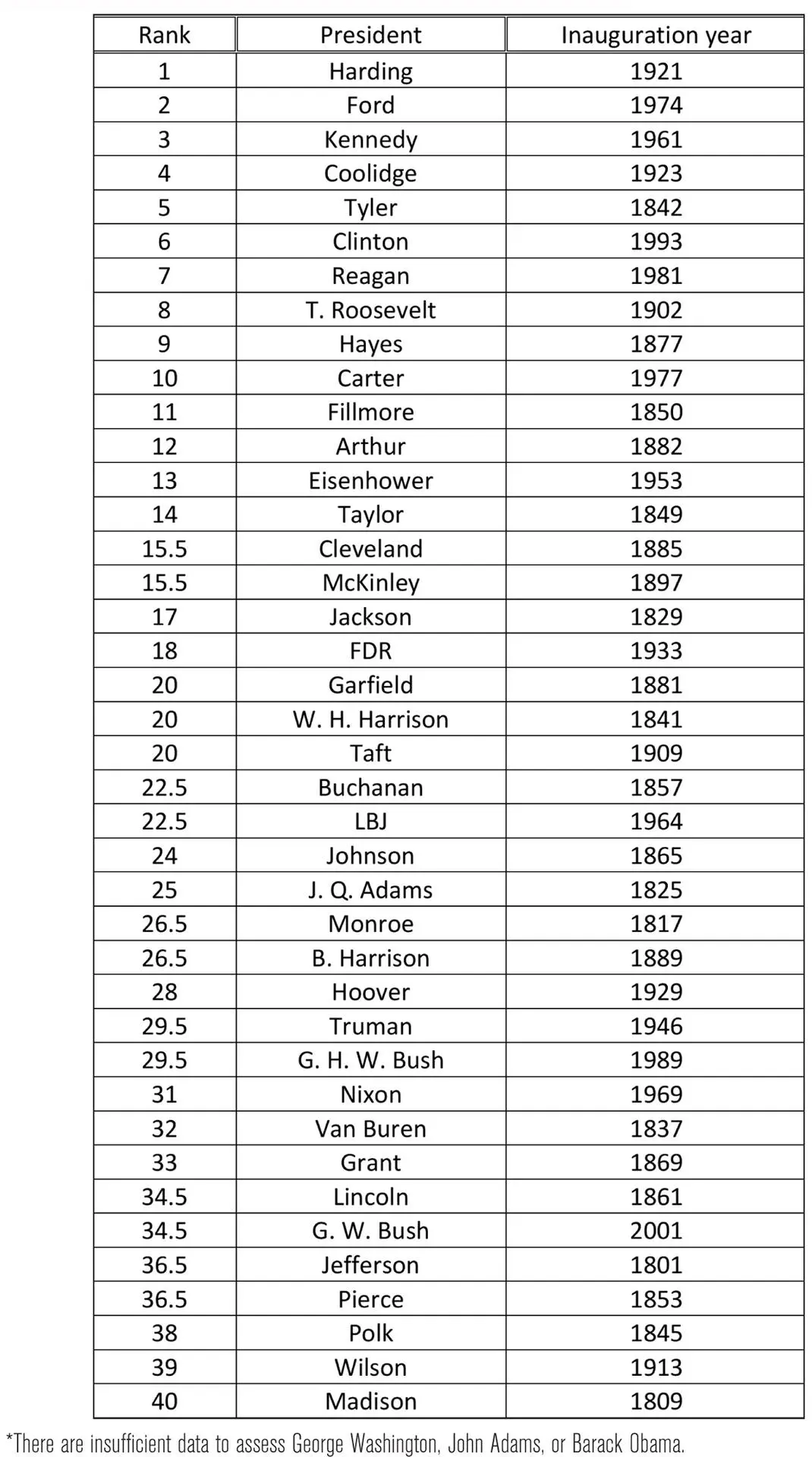

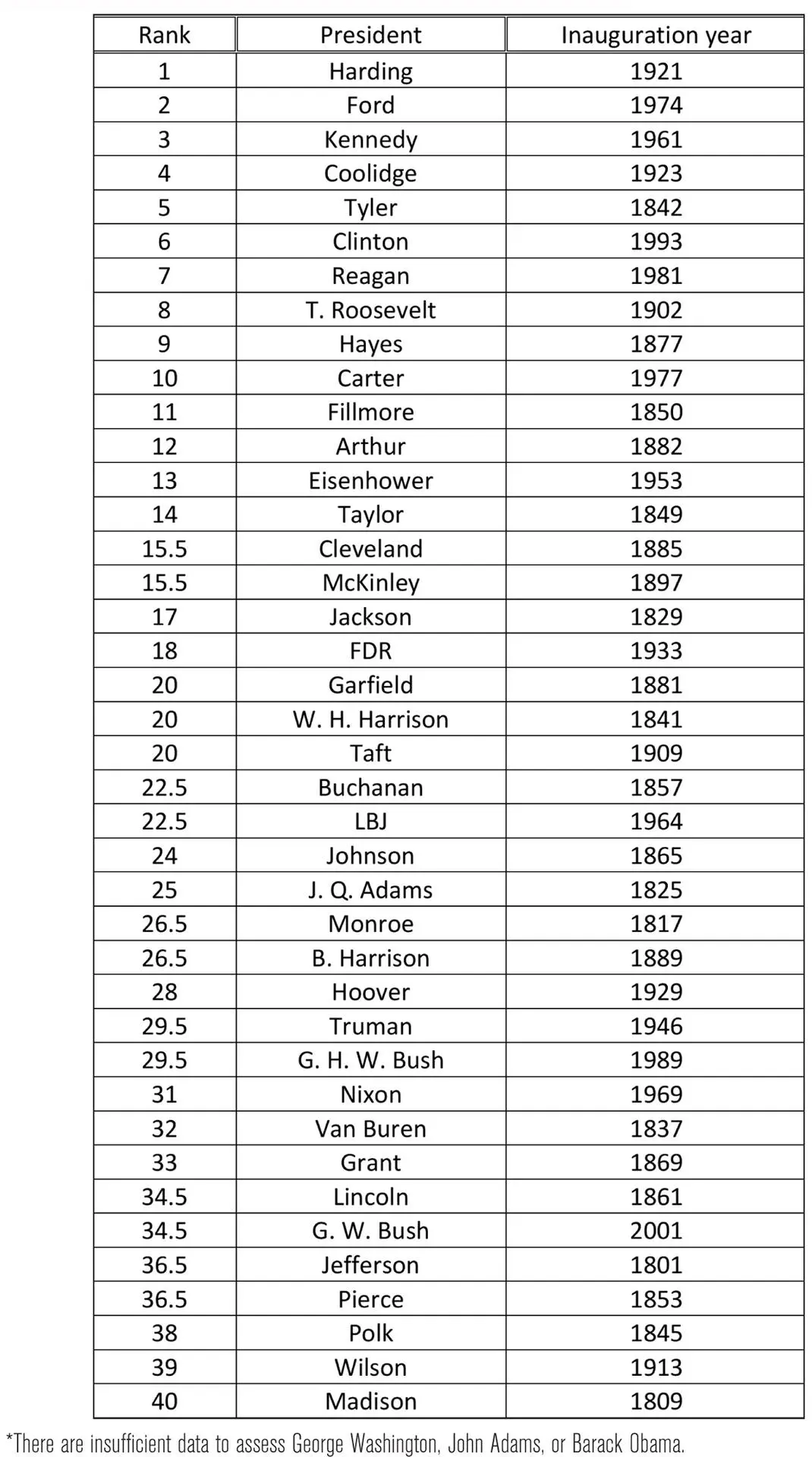

Table C.1 has taken the relevant information on growth rates and absence of US war deaths to rank presidents from best to worst.

One might, of course, tweak this assessment to elevate presidents who, though presiding over many American deaths in war, were responding to attack or inherited a war rather than fomenting it. That might, for instance, improve the rankings of Truman, Nixon, Eisenhower, and Franklin Roosevelt. However we might tweak this, the crucial observation is how little regard we seem to have for presidents credited with a time of peace and prosperity. Maybe, just maybe, that is a failing in “We, the people” that we might wish individually and collectively to reflect upon.

Table C.1. Peace and Prosperity Rankings of US Presidents

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION: E PLURIBUS UNUM

CHAPTER ONE: GEORGE WASHINGTON’S WARS

CHAPTER TWO: CONGRESS’S WAR OF 1812

CHAPTER THREE: ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE PURSUIT OF AMBITION

Robert H. Browne, Abraham Lincoln and the Men of His Time (New York: Katon and Mains, 1901), 285.

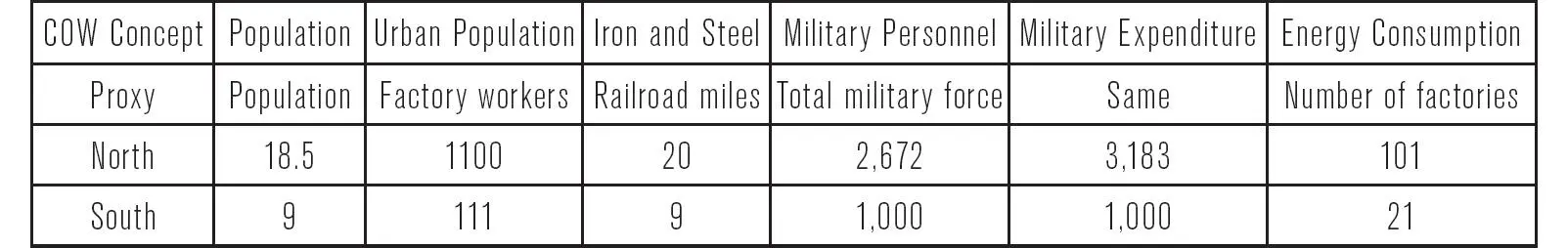

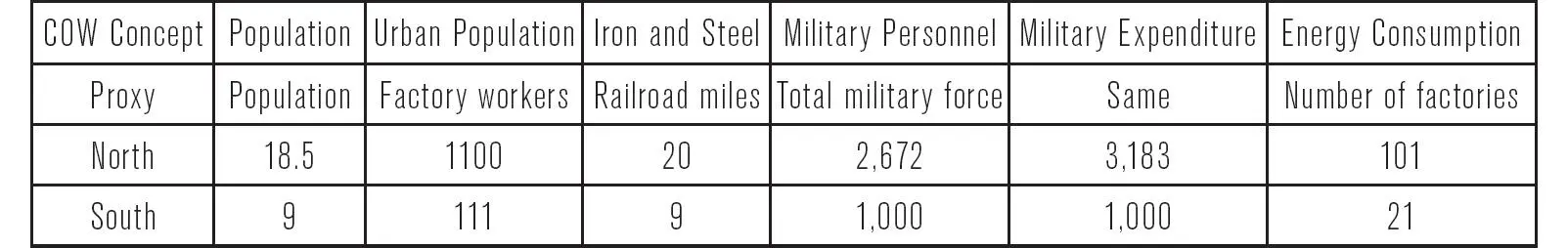

Taking the North’s percentage of the total for North and South on each variable and then finding the average for these variables, the North’s national capability index is equal to approximately 76 percent. Taking the estimated weights for each variable in Bennett and Stam’s method and applying those values to the North and South’s values, we can predict the expected length of the war given their procedure. That yields a median predicted length for the Civil War of 5.89 months.

CHAPTER FOUR: ROOSEVELT’S VANITY

30. John Powell, Encyclopedia of North American Immigration (New York: Facts on File, 2005), 94.

31. See http://www.crf-usa.org/black-history-month/race-and-voting-in-the-segregated-south.

32. Doyle, Inside the Oval Office .

33. A fuller version of the discussion was reported on by the New York Times : “President Orders an Even Break for Minorities in Defense Jobs,” June 26, 1941.

34. Morris J. MacGregor Jr., Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, US Army, 1981), 15.

35. See http://newdeal.feri.org/speeches/1932d.htm.

36. Walter White, A Man Called White (New York: Viking Press, 1948), 191.

37. MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces , 61.

38. Ibid., 63.

39. Ibid., 31–32.

40. James D. Fearon, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49, 3 (Summer 1995): 379–414.

41. Robert Powell, “War as a Commitment Problem,” International Organization 60, 1 (Winter 2006): 169–203.

CHAPTER FIVE: LBJ’S DEFEAT BY DEBIT CARD, W’S VICTORY BY CREDIT CARD

1. When we refer to “Bush,” we generally mean George W. Bush, the forty-third president. When referring to his father, George H. W. Bush, the forty-first president, we will make clear that we are doing so. Whenever the context makes ambiguous which president is being referenced, we will use the full name.

2. http://www.gallup.com/poll/2299/americans-look-back-vietnam-war.aspx. For additional public opinion data, see W. Lunch and P. Sperlich, The Western Political Quarterly 32, no. 1 (1979): 21–44.

3. Pub. L. No. 88–408, 59 Stat. 1031, 6 UST 81 (1964).

Читать дальше