Henry Clay, leader of the War Hawk faction, was a first-term congressman in 1811, but he was not an inexperienced legislator. He had previously served in the United States Senate, his first term having begun in 1806 when he was actually below the constitutionally stipulated age to serve in that body. After five years in the Senate, Clay entered the House, where he was elected as Speaker in his freshman year, a feat that has never been repeated. He used that position to great political advantage by packing congressional committees with fellow War Hawks, thus ensuring committee reports favorable to his prowar position and giving the War Hawks an influence over policy—and leverage with the president—well beyond what their small number in Congress suggested. In explaining his, and implicitly War Hawk, advocacy of war, Clay observed, “No man in the nation desires peace more than I. But I prefer the troubled ocean of war, demanded by the honor and independence of the country, with all its calamities, and desolations, to the tranquil, putrescent pool of ignominious peace.”26 Although Clay was extremely hawkish when it came to arguing for war, he turned out to be much less belligerent when it came to paying for the war.

Support for the war and for the various political factions that made up Congress differed enormously across regions. After John Adams’s single term as president and the death of the Federalist Party’s intellectual leader, Alexander Hamilton, following a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr, the Federalists remained strong only in New England. Hamilton’s policies were for a strong central government with a strong fiscal capacity, internal taxes, a national bank, a strong navy, and a mercantile focus. When Jefferson’s Republican Party came to power, it reversed many of these programs. Expenditures were cut, the army and navy were allowed to dwindle, internal taxes were abolished, the national debt was paid down, and the National Bank’s charter was not renewed when it expired in 1811. The Jeffersonian agenda was popular in the South and in the western, more agrarian states. Indeed, the difference in the popularity of the Federalist and Republican agendas could not have been more starkly demonstrated than in the congressional election of 1812. War, you will recall, was declared in June. The November election five months later produced a surge in Federalist seats in the House of Representatives. The party won 68 seats in 1812, an increase of 32 over the 1810 election. The increase in representation, however, came almost entirely from the Northeast; the Federalists gained almost nothing in the South and exactly nothing in the West where they had zero congressional seats to begin with.

The New England states, Federalist all, were the states in which industry, commerce, fishing, and shipbuilding were especially important. Given these interests, one might expect New Englanders to have had much to gain from the protection of sailors’ rights and from free trade; that is, Madison’s first two grievances. It is likely that he (and Henry Clay), seeking bipartisan support for the war of expansion he contemplated, emphasized maritime grievances in the hope of eliciting Federalist backing. Yet, the New England states, like Federalists elsewhere, stubbornly refused to support the war. New England provided few soldiers or militia units and New England banks generally refused to purchase bonds to help finance the war. Indeed, when Treasury secretary Gallatin could sell only $6 million of an $11 million bond issue, with New Englanders taking very few of the bonds, France’s representative in Washington, Serurier, wrote to the French foreign minister Maret on May 4, 1812, explaining that “they had counted on more national energy on the opening of a first loan for a war so just. This cooling of the national pulse, the resistance which the Northern States seem once more willing to offer the Administration, the defection it meets every day in Congress, all this, joined to its irritation at our measures which make its own system unpopular, adds to its embarrassment and hesitation.”27

The absence of Federalist backing for the war agenda almost certainly resided in two realizations. First, the Federalists likely understood that the War Hawks had little interest in taking actions—such as strengthening the capability of the navy to defend the American coast—that would be beneficial to the Federalist states. Second, seeing how unprepared and unrealistic the War Hawks were with regard to the ease of achieving their territorial goals, the Federalists probably made the correct political assessment by opposing the war, improving their own electoral odds for the 1812 election.

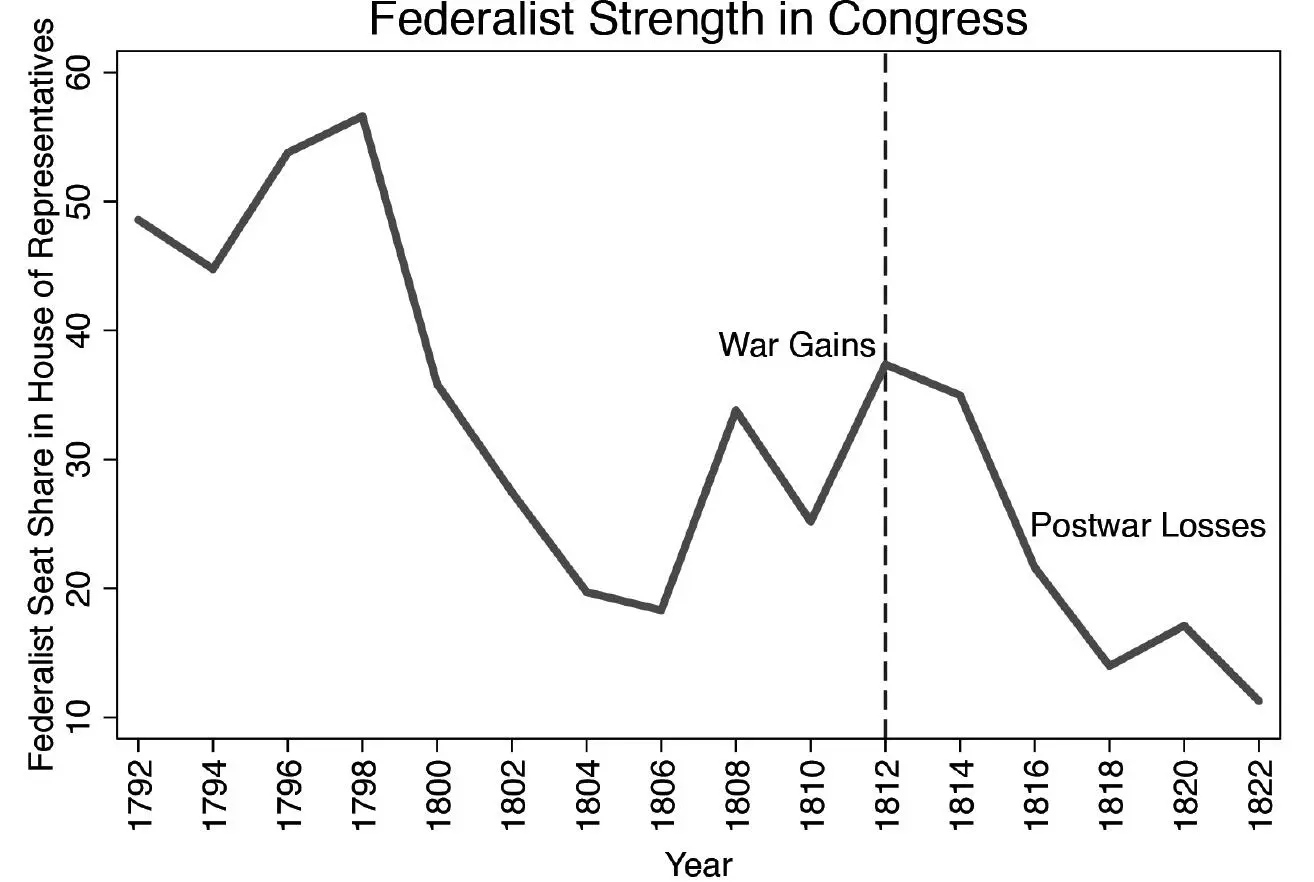

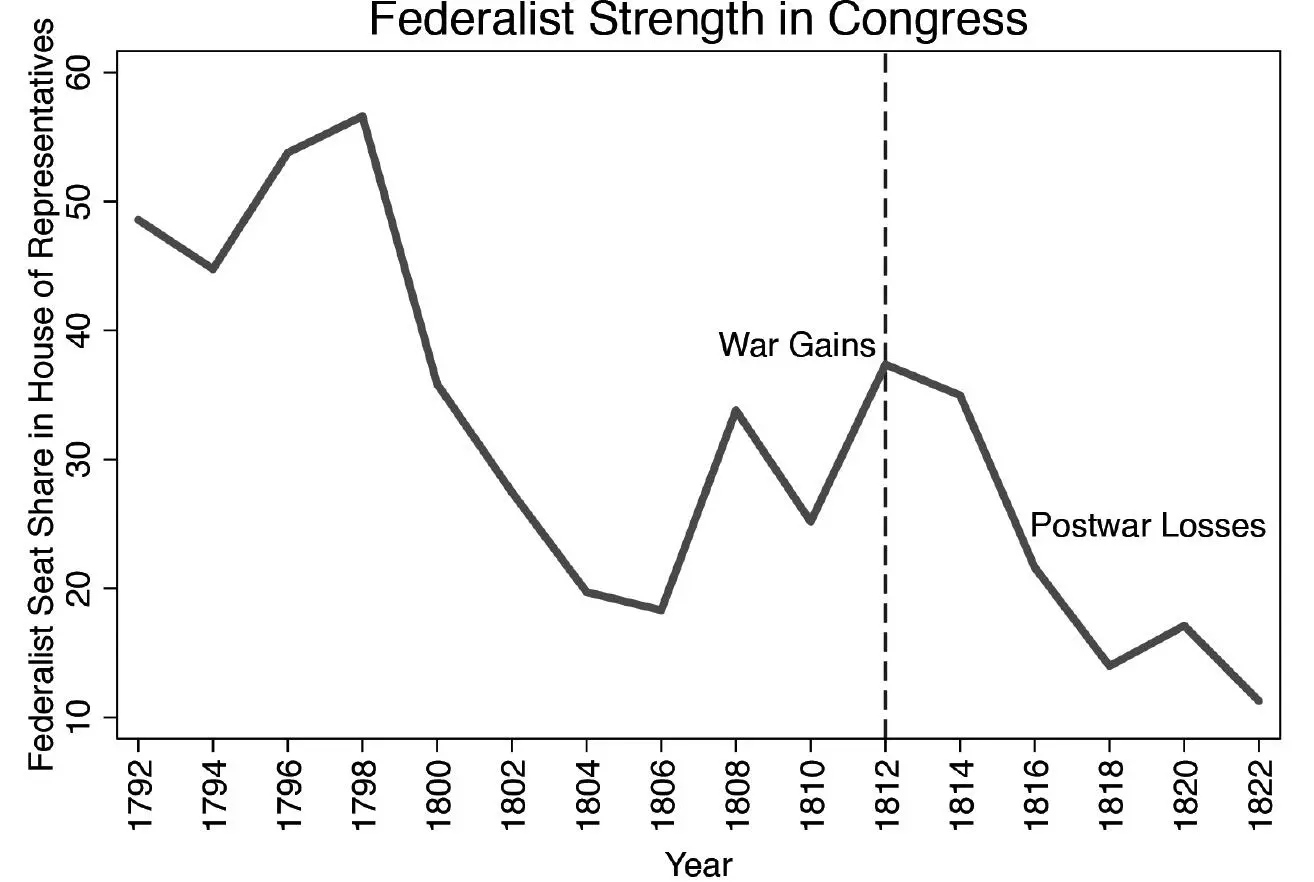

It makes sense for a foreign policy, such as waging war, to garner bipartisan support when it is expected to succeed. Opposing a victorious war effort is unlikely to win many seats for the opposition, as all the kudos go to the party that backed victory. But if the war is expected to fail, then the opposition—the Federalist Party in this case—is more likely to enjoy electoral gains by opposing rather than supporting the war.28 By the November 1812 election, New England voters exposed to the maritime aspects of the war would not have cared about territorial expansion nearly as much as voters in western states did. The upshot was that with the war going badly, as predicted by Federalists, those voters for whom the maritime issues were salient were likely to be anti-Madison, Federalist voters. Only several years later, when the fortunes of war turned, did the voters begin once again to abandon the Federalists. Figure 2.1 shows the rise and decline of Federalist support as a percentage of the Congress to illustrate the partisan swings. Just to the right of the dotted vertical line we see the substantial Federalist gains in the November 1812 election. In 1816, after everyone knows the outcome of the war, the Federalists—having ultimately backed the wrong position—go into a tailspin, ceasing to exist less than a decade later.

The Republican effort to achieve bipartisan support for the declaration of war was a failure. How, then, did the Republicans respond to the lack of Federalist support? They responded by accusing them of being unpatriotic and even of being traitors. In Baltimore such disagreements turned into riots. Federalist newspaper publishers and other prominent Federalists became the objects of mob violence. For their protection, authorities placed Federalists in jail, but the mob broke into the jail and beat, humiliated, and even killed some Federalists.

Figure 2.1. Partisan Swings in Federalist Support

Note: The dotted vertical line denotes the June 1812 declaration of war.

The War Hawks publicly pressed for war on the moral grounds of protecting sailors’ rights and free trade, issues presumably designed to garner support among New Englanders. These issues were less relevant to the War Hawks’ constituents; that is, the people living in the South or on the country’s frontier in such states as Clay’s Kentucky. Having failed to win bipartisan support, the War Hawks turned their emphasis to opportunities for their empowerment that was reminiscent of the motives of the Revolutionary War, namely to rid North America of the British and to remove “savage” Indians from “our frontiers.” Additionally, the War Hawks now had little political incentive to worry about impressment and maritime trade arguments. Speaking in a debate following a Foreign Relations Committee Report on December 9, 1811, War Hawk congressman Felix Grundy of Tennessee set the tone of future argumentation: “This war, if carried successfully, will have its advantages. We shall drive the British from our Continent. . . . I therefore feel anxious not only to add the Floridas to the South, but the Canadas to the North of this empire.”29 Presaging Clay’s arguments for the Missouri Compromise nine years later, Grundy also made an appeal to the need for a balance between North and South. He noted that with the South’s enlargement by acquisition of Louisiana (and, he expected, Florida), the North would be disadvantaged. “I am willing to receive the Canadians as adopted brethren. It will have beneficial political effects; it will preserve the equilibrium of the government. When Louisiana shall be fully peopled, the Northern States will lose their power; they will be at the discretion of others; they can be depressed at pleasure, and then this Union might be endangered.”30 Indeed, he may well have hoped that the appeal to include Canada would be better received by the New England Federalists, who traded with Canada, than the general War Hawk call for war, but he did not emphasize how the war would protect Federalist New England’s maritime concerns!

Читать дальше