A similar suspension of disbelief will be necessary for you to master another case of tricky case, the difference between who and whom . You may be inclined to agree with the writer Calvin Trillin when he wrote, “As far as I’m concerned, whom is a word that was invented to make everyone sound like a butler.” But in chapter 6 we’ll see that this is an overstatement. There are times when even nonbutlers need to know their who from their whom, and that will require you, once again, to brush up on your trees.

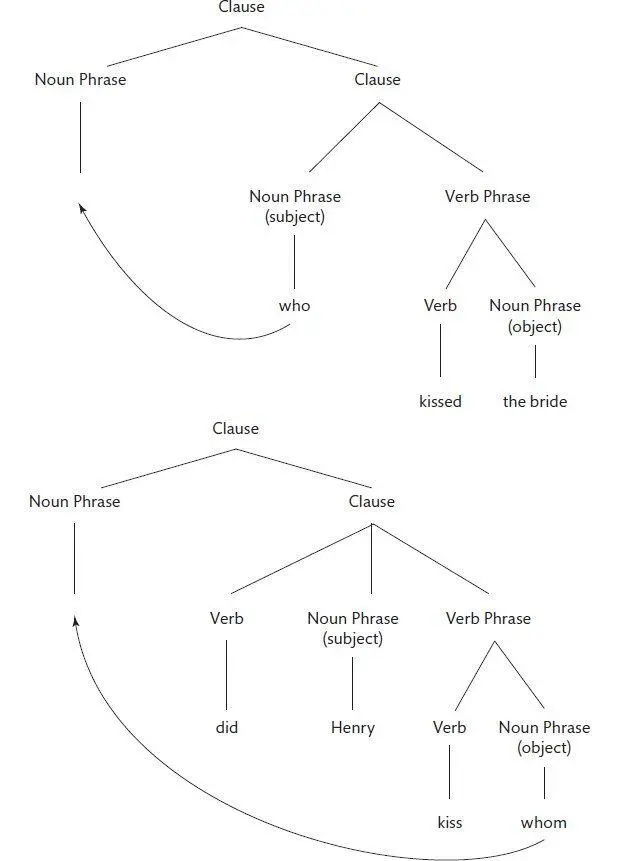

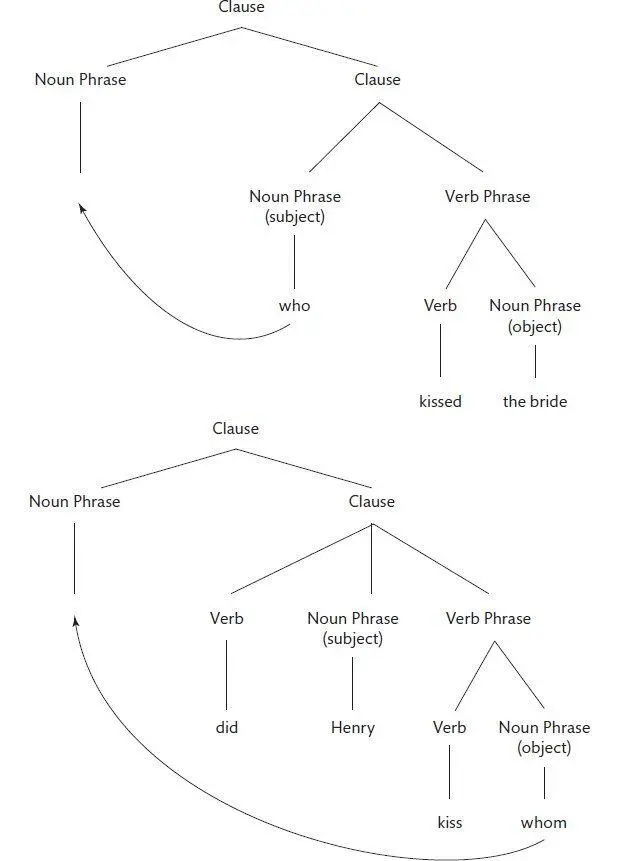

At first glance, the difference is straightforward: who is nominative, like I, she, he, we, and they , and is used for subjects; whom is accusative, like me, her, him, us , and them, and is used for objects. So in theory, anyone who laughs at Cookie Monster when he says Me want cookie should already know when to use who and when to use whom (assuming they have opted to use whom in the first place). We say He kissed the bride, so we ask Who kissed the bride? We say Henry kissed her, so we ask Whom did Henry kiss? The difference can be appreciated by visualizing the wh- words in their deep-structure positions, before they were moved to the front of the sentence, leaving behind a gap. 13

But in practice, our minds can’t take in a whole tree at a glance, so when a sentence gets more complicated, any lapse of attention to the link between the who/whom and the gap can lead to the wrong one being chosen: 14

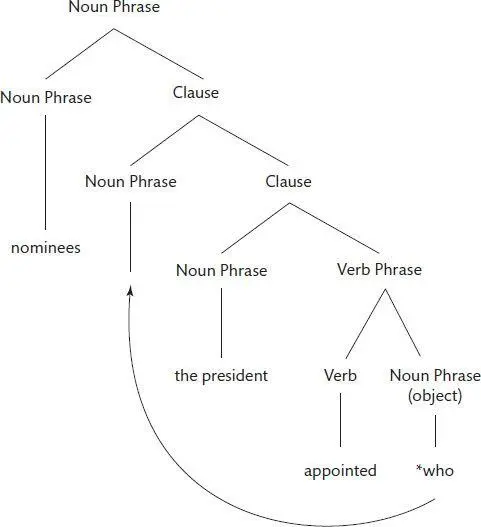

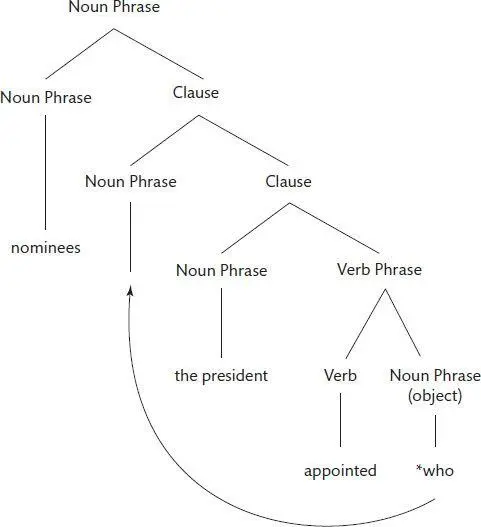

Under the deal, the Senate put aside two nominees for the National Labor Relations Board who the president appointed __ during a Senate recess.

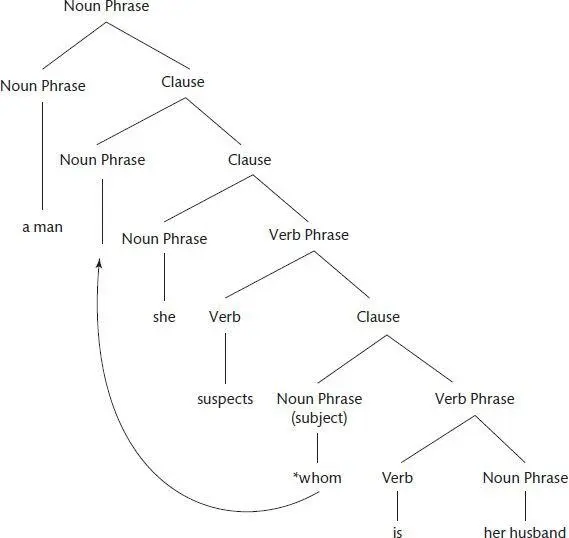

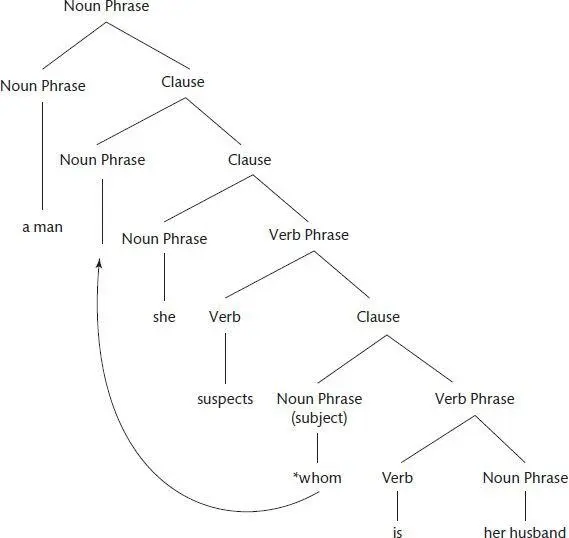

The French actor plays a man whom she suspects __ is her husband, missing since World War II.

The errors could have been avoided by mentally moving the who or whom back into the gap and sounding out the sentence (or, if your intuitions about who and whom are squishy, inserting he or him in the gap instead).

The first replacement yields the president appointed who , which corresponds to the president appointed he , which sounds entirely wrong; therefore it should be whom (corresponding to him ) instead. (I’ve inserted an asterisk to remind you that the who doesn’t belong there.) The second yields whom is her husband (or him is her husband ), which is just as impossible; it should be who. Again, I’m explaining the official rules so that you will know how to satisfy an editor or work as a butler; in chapter 6 I’ll return to the question of whether the official rules are legitimate and thus whether these really should be counted as errors.

Though tree-awareness can help a writer avoid errors (and, as we shall see, help him make life easy for his readers), I am not suggesting that you literally diagram your sentences. No writer does that. Nor am I even suggesting that you form mental images of trees while you write. The diagrams are just a way to draw your attention to the cognitive entities that are active in your mind as you put together a sentence. The conscious experience of “thinking in trees” does not feel like looking at a tree; it’s the more ethereal sensation of apprehending how words are grouped in phrases and zooming in on the heads of those phrases while ignoring the rest of the clutter. For example, the way to avoid the error The impact of the cuts have not been felt is to mentally strip the phrase the impact of the cuts down to its head, the impact, and then imagine it with have: the error the impact have not been felt will leap right out. Tree-thinking also consists in mentally tracing the invisible filament that links a filler in a sentence to the gap that it plugs, which allows you to verify whether the filler would work if it were inserted there. You un-transform the research the scientists have made __ back into the scientists have made the research; you undo whom she suspects __ is her husband and get she suspects whom is her husband . As with any form of mental self-improvement, you must learn to turn your gaze inward, concentrate on processes that usually run automatically, and try to wrest control of them so that you can apply them more mindfully.

Once a writer has ensured that the parts of a sentence fit together in a tree, the next worry is whether the reader can recover that tree, which she needs to do to make sense of the sentence. Unlike computer programming languages, where the braces and parentheses that delimit expressions are actually typed into the string for everyone to see, the branching structure of an English sentence has to be inferred from the ordering and forms of the words alone. That imposes two demands on the long-suffering reader. The first is to find the correct branches, a process called parsing. The second is to hold them in memory long enough to dig out the meaning, at which point the wording of the phrase may be forgotten and the meaning merged with the reader’s web of knowledge in long-term memory. 15

As the reader works through a sentence, plucking off a word at a time, she is not just threading it onto a mental string of beads. She is also growing branches of a tree upward. When she reads the word the, for example, she figures she must be hearing a noun phrase. Then she can anticipate the categories of words that can complete it; in this case, it’s likely to be a noun. When the word does come in (say, cat ), she can attach it to the dangling branch tip.

So every time a writer adds a word to a sentence, he is imposing not one but two cognitive demands on the reader: understanding the word, and fitting it into the tree. This double demand is a major justification for the prime directive “Omit needless words.” I often find that when a ruthless editor forces me to trim an article to fit into a certain number of column-inches, the quality of my prose improves as if by magic. Brevity is the soul of wit, and of many other virtues in writing.

The trick is figuring out which words are “needless.” Often it’s easy. Once you set yourself the task of identifying needless words, it’s surprising how many you can find. A shocking number of phrases that drop easily from the fingers are bloated with words that encumber the reader without conveying any content. Much of my professional life consists of reading sentences like this:

Our study participants show a pronounced tendency to be more variable than the norming samples, although this trend may be due partly to the fact that individuals with higher measured values of cognitive ability are more variable in their responses to personality questionnaires.

a pronounced tendency to be more variable: Is there really a difference between “being more variable” (three words in a three-level, seven-branch tree) and “having a pronounced tendency to be more variable” (eight words, six levels, twenty branches)? Even worse, this trend may be due partly to the fact that burdens an attentive reader with ten words, seven levels, and more than two dozen branches. Total content? Approximately zero. The forty-three-word sentence can easily be reduced to nineteen, which prunes the number of branches even more severely:

Читать дальше