As a child I was taught, for example, that the words soap in soap flakes and that in that boy were adjectives, because they modify nouns. But this confuses the grammatical category “adjective” with the grammatical function “modifier.” There’s no need to wave a magic wand over the noun soap and transmute it into an adjective just because of what it’s doing in this phrase. It’s simpler to say that sometimes a noun can modify another noun. In the case of that in that boy, Miss Thistlebottom got the function wrong, too: it’s determiner, not modifier. How do we know? Because determiners and modifiers are not interchangeable. You can say Look at the boy or Look at that boy (determiners), but not Look at tall boy (a modifier). You can say Look at the tall boy (determiner + modifier), but not Look at the that boy (determiner + determiner).

I was also taught that a “noun” is a word for a person, place, or thing, which confuses a grammatical category with a semantic category. The comedian Jon Stewart was confused, too, because on his show he criticized George W. Bush’s “War on Terror” by protesting, “ Terror isn’t even a noun!” 6What he meant was that terror is not a concrete entity, in particular a group of people organized into an enemy force. Terror, of course, is a noun, together with thousands of other words that don’t refer to people, places, or things, including the nouns word, category, show, war, and noun, to take just some examples from the past few sentences. Though nouns are often the names for people, places, and things, the noun category can only be defined by the role it plays in a family of rules. Just as a “rook” in chess is defined not as the piece that looks like a little tower but as the piece that is allowed to move in certain ways in the game of chess, a grammatical category such as “noun” is defined by the moves it is allowed to make in the game of grammar. These moves include the ability to appear after a determiner ( the king ), the requirement to have an oblique rather than a direct object ( the king of Thebes , not the king Thebes ), and the ability to be marked for plural number ( kings ) and genitive case ( king’s ). By these tests, terror is certainly a noun: the terror, terror of being trapped, the terror’s lasting impact.

Now we can see why the word Sophocles’ shows up in the tree with the category “noun” and the function “determiner” rather than “adjective.” The word belongs to the noun category, just as it always has; Sophocles did not suddenly turn into an adjective just because it is parked in front of another noun. And its function is determiner because it acts in the same way as the words the and that and differently from a clear-cut modifier like famous: you can say In Sophocles’ play or In the play, but not In famous play .

At this point you may be wondering: What’s with “genitive”? Isn’t that just what we were taught is the possessive? Well, “possessive” is a semantic category, and the case indicated by the suffix ’s and by pronouns like his and my needn’t have anything to do with possession. When you think about it, there is no common thread of ownership, or any other meaning, across the phrases Sophocles’ play, Sophocles’ nose, Sophocles’ toga, Sophocles’ mother, Sophocles’ hometown, Sophocles’ era, and Sophocles’ death. All that the Sophocles’ s have in common is that they fill the determiner slot in the tree and help you determine which play, which nose, and so on, the speaker had in mind.

More generally, it’s essential to keep an open mind about how to diagram a sentence rather than assuming that everything you need to know about grammar was figured out before you were born. Categories, functions, and meanings have to be ascertained empirically, by running little experiments such as substituting a phrase whose category you don’t know for one you do know and seeing whether the sentence still works. Based on these mini-experiments, modern grammarians have sorted words into grammatical categories that sometimes differ from the traditional pigeonholes.

There is a reason why the list on page 84, for example, doesn’t have the traditional category called “conjunction,” with the subtypes “coordinating conjunction” (words like and and or ) and “subordinating conjunction” (words like that and if ). It turns out that coordinators and subordinators have nothing in common, and there is no category called “conjunction” that includes them both. For that matter, many of the words that were traditionally called subordinating conjunctions, like before and after, are actually prepositions. 7The after in after the love has gone, for example, is just the after which appears in after the dance, which everyone agrees is a preposition. It was just a failure of the traditional grammarians to distinguish categories from functions that blinded them to the realization that a preposition could take a clause, not just a noun phrase, as its object.

Why does any of this matter? Though you needn’t literally diagram sentences or master a lot of jargon to write well, the rest of this chapter will show you a number of ways in which a bit of syntactic awareness can help you out. First, it can help you avoid some obvious grammatical errors, those that are errors according to your own lights. Second, when an editor or a grammatical stickler claims to find an error in a sentence you wrote, but you don’t see anything wrong with it, you can at least understand the rule in question well enough to decide for yourself whether to follow it. As we shall see in chapter 6, many spurious rules, including some that have made national headlines, are the result of bungled analyses of grammatical categories like adjective, subordinator, and preposition. Finally, an awareness of syntax can help you avoid ambiguous, confusing, and convoluted sentences. All of this awareness depends on a basic grasp of what grammatical categories are, how they differ from functions and meanings, and how they fit into trees.

Trees are what give language its power to communicate the links between ideas rather than just dumping the ideas in the reader’s lap. But they come at a cost, which is the extra load they impose on memory. It takes cognitive effort to build and maintain all those invisible branches, and it’s easy for reader and writer alike to backslide into treating a sentence as just one damn word after another.

Let’s start with the writer. When weariness sets in, a writer’s ability to behold an entire branch of the tree can deteriorate. His field of vision shrinks to a peephole, and he sees just a few adjacent words in the string at a time. Most grammatical rules are defined over trees, not strings, so this momentary tree-blindness can lead to pesky errors.

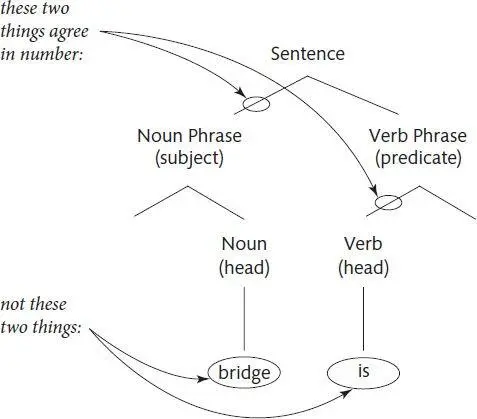

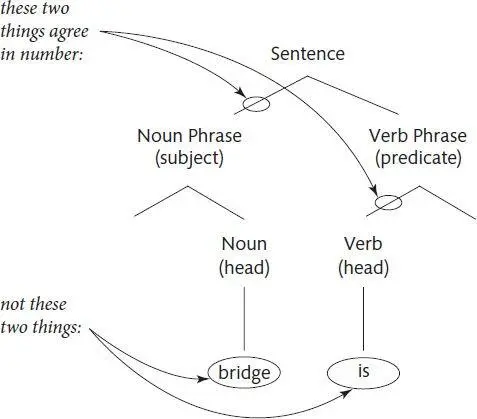

Take agreement between the subject and the verb: we say The bridge is crowded, but The bridges are crowded. It’s not a hard rule to follow. Children pretty much master it by the age of three, and errors such as I can has cheezburger and I are serious cat are so obvious that a popular Internet meme (LOLcats) facetiously attributes them to cats. But the “subject” and “verb” that have to agree are defined by branches in the tree, not words in the string:

Читать дальше