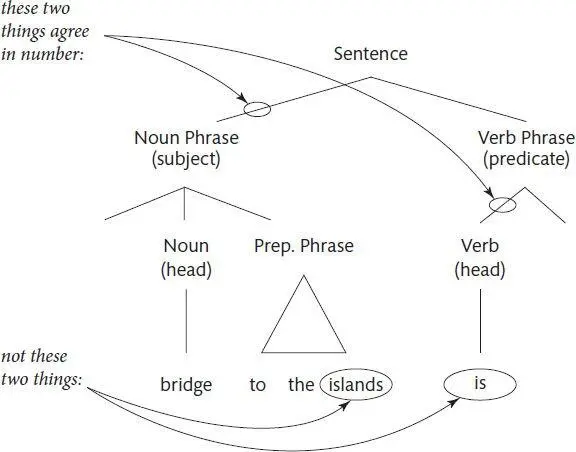

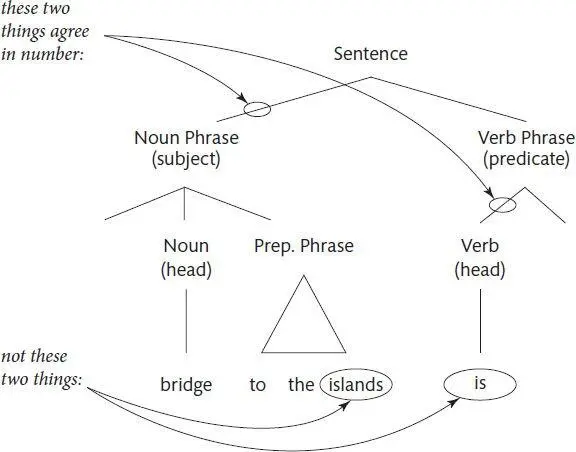

You might be thinking, What difference does it make? Doesn’t the sentence come out the same either way? The answer is that it doesn’t. If you fatten up the subject by stuffing some words at the end, as in the diagram below, so that bridge no longer comes right before the verb, then agreement—defined over the tree—is unaffected. We still say The bridge to the islands is crowded, not The bridge to the islands are crowded.

But thanks to tree-blindness, it’s common to slip up and type The bridge to the islands are crowded . If you haven’t been keeping the tree suspended in memory, the word islands, which is ringing in your mind’s ear just before you type the verb, will contaminate the number you give the verb. Here are a few other agreement errors that have appeared in print: 8

The readiness of our conventional forces are at an all-time low.

At this stage, the accuracy of the quotes have not been disputed.

The popularity of “Family Guy” DVDs were partly credited with the 2005 revival of the once-canceled Fox animated comedy.

The impact of the cuts have not hit yet.

The maneuvering in markets for oil, wheat, cotton, coffee and more have brought billions in profits to investment banks.

They’re easy to miss. As I am writing this chapter, every few pages I see the green wiggly line of Microsoft Word’s grammar checker, and usually it flags an agreement error that slipped under my tree-spotting radar. But even the best software isn’t smart enough to assign trees reliably, so writers cannot offload the task of minding the tree onto their word processors. In the list of agreement errors above, for example, the last two sentences appear on my screen free of incriminating squiggles.

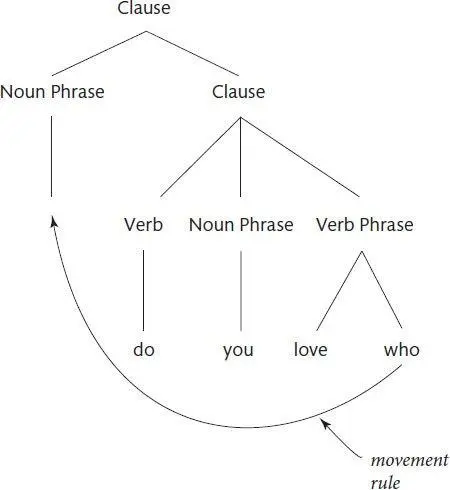

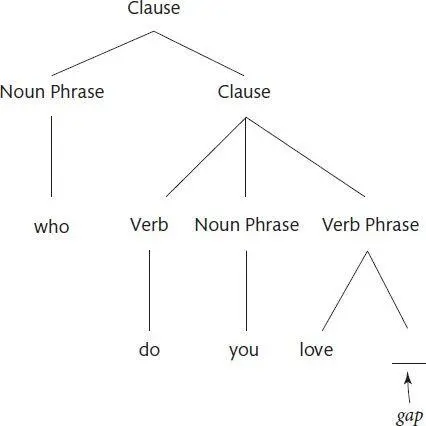

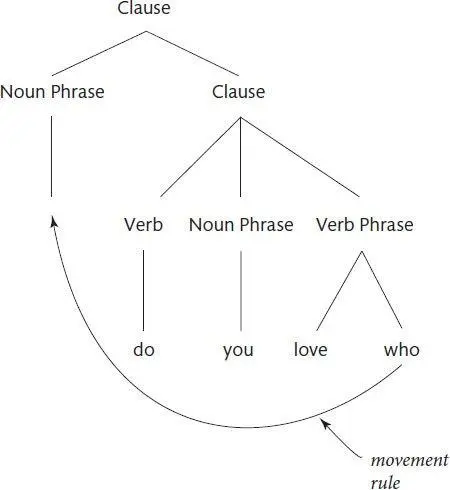

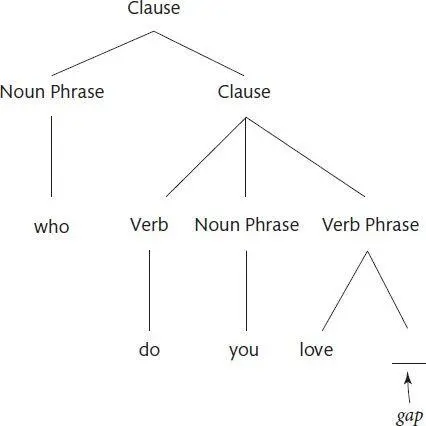

Wedging an extra phrase into a tree is just one of the ways in which a subject can be separated from its verb. Another is the grammatical process that inspired the linguist Noam Chomsky to propose his famous theory in which a sentence’s underlying tree—its deep structure—is transformed by a rule that moves a phrase into a new position, yielding a slightly altered tree called a surface structure. 9This process is responsible, for example, for questions containing wh- words, such as Who do you love? and Which way did he go? (Don’t get hung up on the choice between who and whom just yet—we’ll get to that later.) In the deep structure, the wh- word appears in the position you’d expect for an ordinary sentence, in this case after the verb love, as in I love Lucy. The movement rule then brings it to the front of the sentence, leaving a gap (the underscored blank) in the surface structure. (From here on, I’ll keep the trees uncluttered by omitting unnecessary labels and branches.)

Deep Structure

Surface Structure

We understand the question by mentally filling the gap with the phrase that was moved out of it. Who do you love __ ? means “For which person do you love that person?”

The movement rule also generates a common construction called a relative clause, as in the spy who __ came in from the cold and the woman I love __. A relative clause is a clause with a gap in it ( I love __) which modifies a noun phrase ( the woman ). The position of the gap indicates the role that the modified phrase played in the deep structure; to understand the relative clause, we mentally fill it back in. The first example means “the spy such that the spy came in from the cold.” The second means “the woman such that I love the woman.”

The long distance between a filler and a gap can be hazardous to writer and reader alike. When we’re reading and we come across a filler (like who or the woman ), we have to hold it in memory while we handle all the material that subsequently pours in, until we locate the gap that it is meant to fill. 10Often that is too much for our thimble-sized memories to handle, and we get distracted by the intervening words:

The impact, which theories of economics predict ____ are bound to be felt sooner or later, could be enormous.

Did you even notice the error? Once you plug the filler the impact into the gap after predict, yielding the impact are bound to be felt, you see that the verb must be is, not are; the error is as clear as I are serious cat . But the load on memory can allow the error to slip by.

Agreement is one of several ways in which one branch of a tree can be demanding about what goes into another branch. This demandingness is called government, and it can also be seen in the way that verbs and adjectives are picky about their complements. We make plans but we do research; it would sound odd to say that we do plans or make research. Bad people oppress their victims (an object), rather than oppressing against their victims (an oblique object); at the same time, they may discriminate against their victims, but not discriminate them. Something can be identical to something else, but must coincide with it; the words identical and coincide demand different prepositions. When phrases are rearranged or separated, a writer can lose track of what requires what else, and end up with an annoying error:

Among the reasons for his optimism about SARS is the successful research that Dr. Brian Murphy and other scientists have made at the National Institutes of Health. 11

People who are discriminated based on their race are often resentful of their government and join rebel groups.

The religious holidays to which the exams coincide are observed by many of our students.

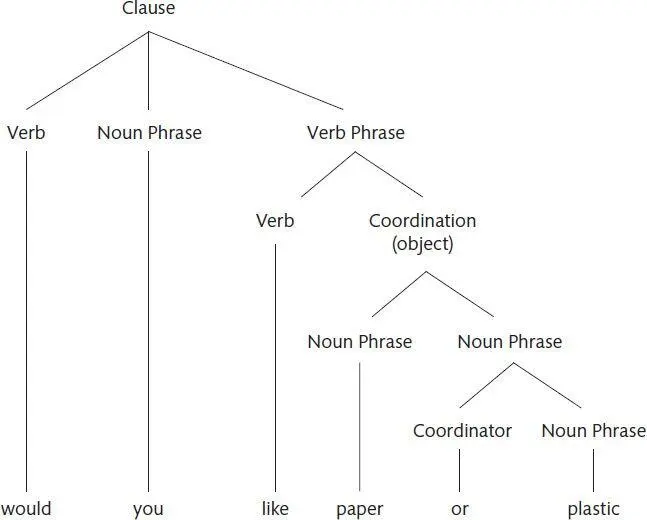

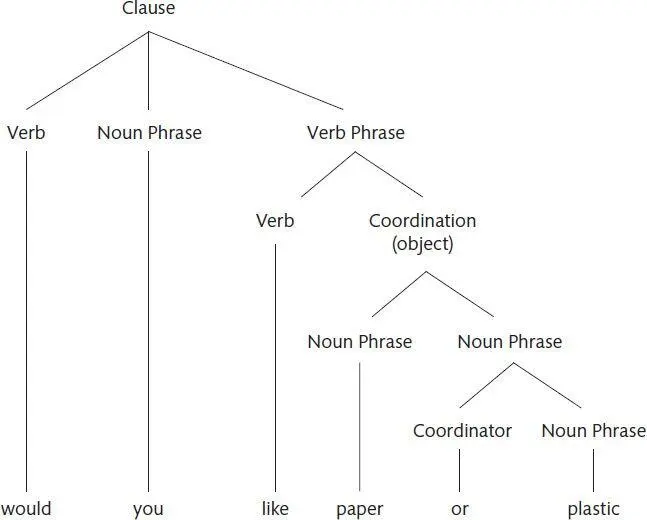

One of the commonest forms of tree-blindness consists of a failure to look carefully at each branch of a coordination. A coordination, traditionally called a conjunction, is a phrase composed of two or more phrases which are linked by a coordinator ( the land of the free and the home of the brave; paper or plastic ) or strung together with commas ( Are you tired, run down, listless? ).

Each of the phrases in a coordination has to work in that position on its own, as if the other phrases weren’t there, and they must have the same function (object, modifier, and so on). Would you like paper or plastic? is a fine sentence because you can say Would you like paper? with paper as the object of like, and you can also say Would you like plastic? with plastic as the object of like. Would you like paper or conveniently? is ungrammatical, because conveniently is a modifier, and it’s a modifier that doesn’t work with like; you would never say Would you like conveniently? No one is tempted to make that error, because like and conveniently are cheek by jowl, which makes the clash obvious. And no one is tempted to say Would you like paper or conveniently? because they can mentally block out the intervening paper and or, whereupon the clash between like and conveniently becomes just as blatant. That’s the basis of the gag title of the comedian Stephen Colbert’s 2007 bestseller, intended to flaunt the illiteracy of his on-screen character: I Am America (And So Can You!).

Читать дальше