Our participants are more variable than the norming samples, perhaps because smarter people respond more variably to personality questionnaires.

Here are a few other morbidly obese phrases, together with leaner alternatives that often mean the same thing: 16

make an appearance with

appear with

is capable of being

can be

is dedicated to providing

provides

in the event that

if

it is imperative that we

we must

brought about the organization of

organized

significantly expedite the process of

speed up

on a daily basis

daily

for the purpose of

to

in the matter of

about

in view of the fact that

since

owing to the fact that

because

relating to the subject of

regarding

have a facilitative impact

help

were in great need of

needed

at such time as

when

It is widely observed that X

X

Several kinds of verbiage are perennial targets for the delete key. Light verbs such as make, do, have, bring, put, and take often do nothing but create a slot for a zombie noun, as in make an appearance and put on a performance. Why not just use the verb that spawned the zombie in the first place, like appear or perform ? A sentence beginning with It is or There is is often a candidate for liposuction: There is competition between groups for resources works just fine as Groups compete for resources. Other globs of verbal fat include the metaconcepts we suctioned out in chapter 2, including matter, view, subject, process, basis, factor, level, and model .

Omitting needless words, however, does not mean cutting out every single word that is redundant in context. As we shall see, many omissible words earn their keep by preventing the reader from making a wrong turn as she navigates her way through the sentence. Others fill out a phrase’s rhythm, which can also make the sentence easier for the reader to parse. Omitting such words is taking the prime directive too far. There is a joke about a peddler who decided to train his horse to get by without eating. “First I fed him every other day, and he did just fine. Then I fed him every third day. Then every fourth day. But just I was getting him down to one meal a week, he died on me!”

The advice to omit needless words should not be confused with the puritanical edict that all writers must pare every sentence down to the shortest, leanest, most abstemious version possible. Even writers who prize clarity don’t do this. That’s because the difficulty of a sentence depends not just on its word count but on its geometry . Good writers often use very long sentences, and they garnish them with words that are, strictly speaking, needless. But they get away with it by arranging the words so that a reader can absorb them a phrase at a time, each phrase conveying a chunk of conceptual structure.

Take this excerpt from a 340-word soliloquy in a novel by Rebecca Goldstein. 17The speaker is a professor who has recently achieved professional and romantic fulfillment and is standing on a bridge on a cold, starry night trying to articulate his wonder at being alive:

Here it is then: the sense that existence is just such a tremendous thing, one comes into it, astonishingly, here one is, formed by biology and history, genes and culture, in the midst of the contingency of the world, here one is, one doesn’t know how, one doesn’t know why, and suddenly one doesn’t know where one is either or who or what one is either, and all that one knows is that one is a part of it, a considered and conscious part of it, generated and sustained in existence in ways one can hardly comprehend, all the time conscious of it, though, of existence, the fullness of it, the reaching expanse and pulsing intricacy of it, and one wants to live in a way that at least begins to do justice to it, one wants to expand one’s reach of it as far as expansion is possible and even beyond that, to live one’s life in a way commensurate with the privilege of being a part of and conscious of the whole reeling glorious infinite sweep, a sweep that includes, so improbably, a psychologist of religion named Cass Seltzer, who, moved by powers beyond himself, did something more improbable than all the improbabilities constituting his improbable existence could have entailed, did something that won him someone else’s life, a better life, a more brilliant life, a life beyond all the ones he had wished for in the pounding obscurity of all his yearnings.

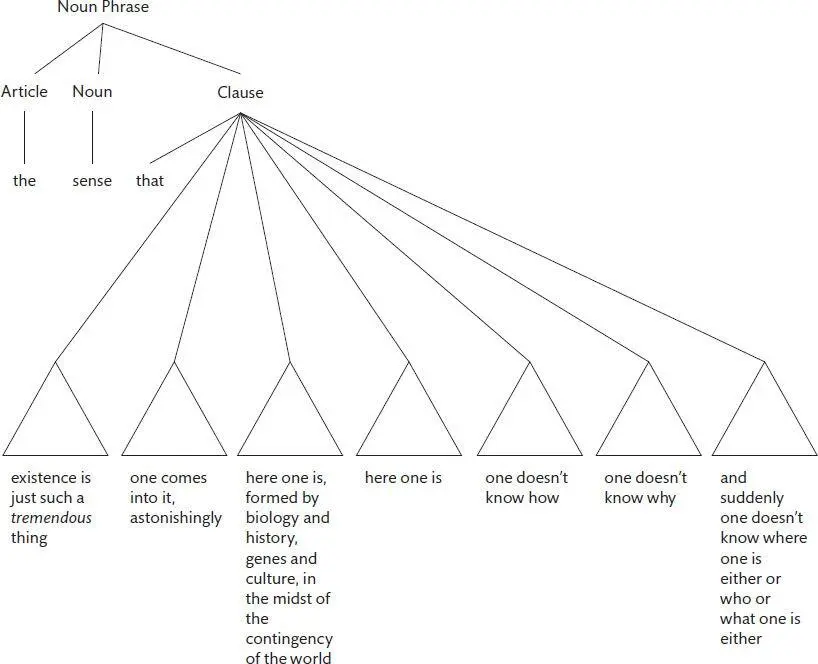

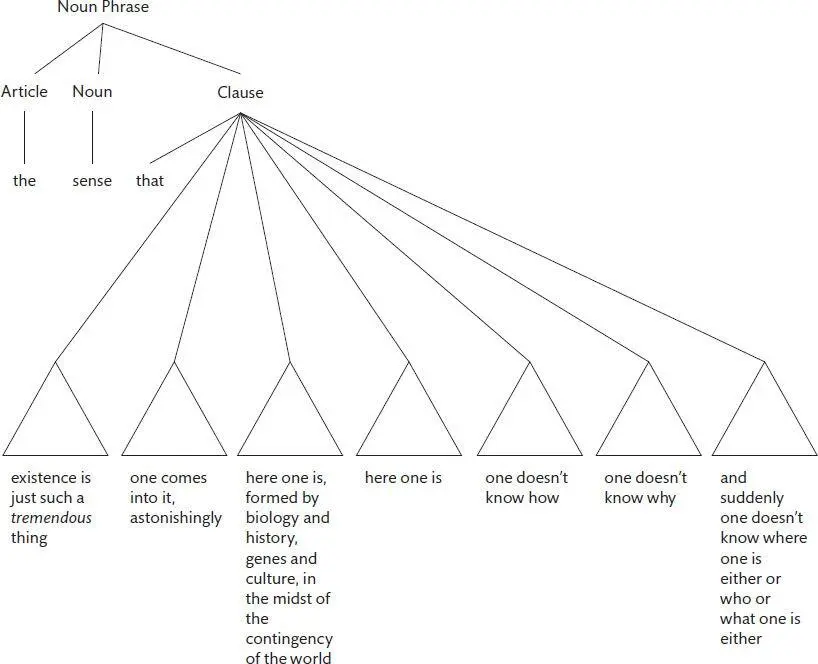

For all its length and lexical exuberance, the sentence is easy to follow, because the reader never has to keep a phrase suspended in memory for long while new words pour in. The tree has been shaped to spread the cognitive load over time with the help of two kinds of topiary. One is a flat branching structure, in which a series of mostly uncomplicated clauses are concatenated side by side with and or with commas. The sixty-two words following the colon, for example, consist mainly of a very long clause which embraces seven self-contained clauses (shown as triangles) ranging from three to twenty words long:

The longest of these embedded clauses, the third and the last, are also flattish trees, each composed of simpler phrases joined side by side with commas or with or .

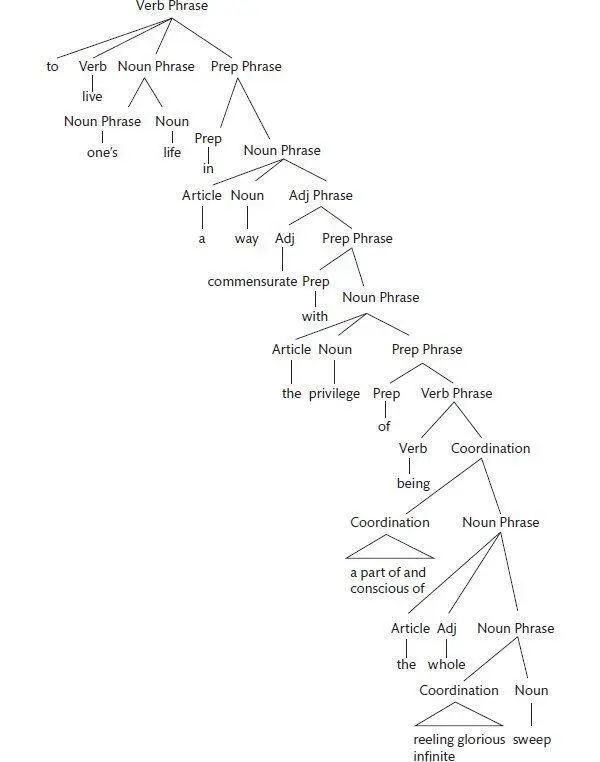

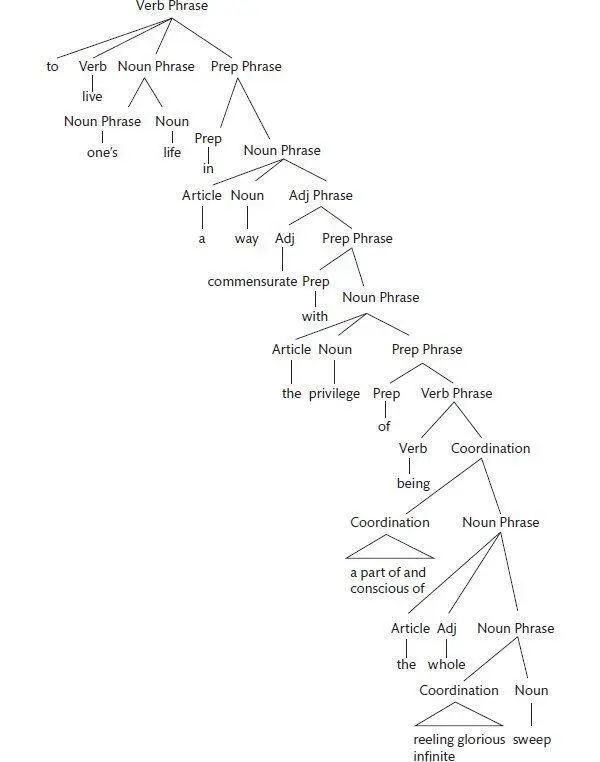

Even when the sentence structure gets more complicated, a reader can handle the tree, because its geometry is mostly right-branching. In a right-branching tree, the most complicated phrase inside a bigger phrase comes at the end of it, that is, hanging from the rightmost branch. That means that when the reader has to handle the complicated phrase, her work in analyzing all the other phrases is done, and she can concentrate her mental energy on that one. The following twenty-five-word phrase is splayed along a diagonal axis, indicating that it is almost entirely right-branching:

The only exceptions, where the reader has to analyze a downstairs phrase before the upstairs phrase is complete, are the two literary flourishes marked by the triangles.

English is predominantly a right-branching language (unlike, say, Japanese or Turkish), so right-branching trees come naturally to its writers. The full English menu, though, offers them a few left-branching options. A modifier phrase can be moved to the beginning, as in the sentence In Sophocles’ play, Oedipus married his mother (the tree on page 82 displays the complicated left branch). These front-loaded modifiers can be useful in qualifying a sentence, in tying it to information mentioned earlier, or simply in avoiding the monotony of having one right-branching sentence after another. As long as the modifier is short, it poses no difficulty for the reader. But if it starts to get longer it can force a reader to entertain a complicated qualification before she has any idea what it is qualifying. In the following sentence, the reader has to parse thirty-four words before she gets to the part that tells her what the sentence is about, namely policymakers : 18

Because most existing studies have examined only a single stage of the supply chain, for example, productivity at the farm, or efficiency of agricultural markets, in isolation from the rest of the supply chain, policymakers have been unable to assess how problems identified at a single stage of the supply chain compare and interact with problems in the rest of the supply chain.

Читать дальше