Another common left-branching construction consists of a noun modified by a complicated phrase that precedes it:

Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Failed password security question answer attempts limit

The US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control

Ann E. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government Michael Sandel

T-fal Ultimate Hard Anodized Nonstick Expert Interior Thermo-Spot Heat Indicator Anti-Warp Base Dishwasher Safe 12-Piece Cookware Set

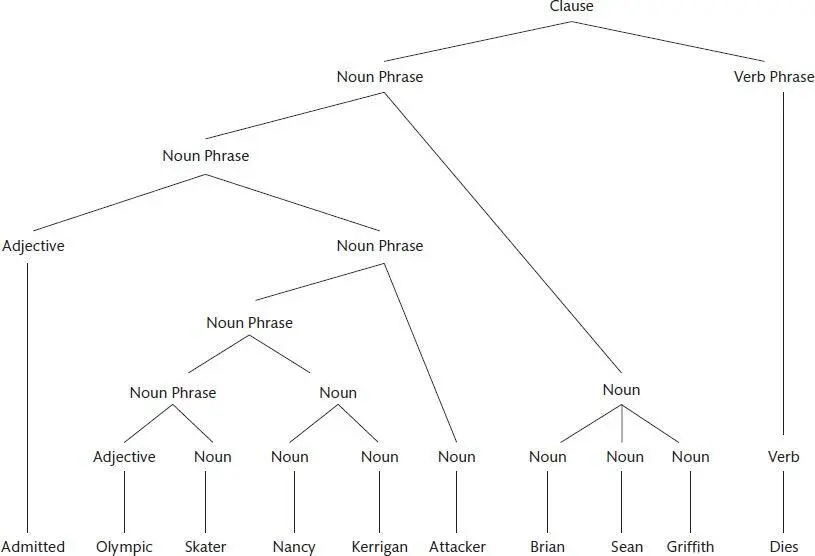

Academics and bureaucrats concoct them all too easily; I once came up with a monstrosity called the relative passive surface structure acceptability index . If the left branch is slender enough, it is generally understandable, albeit top-heavy, with all those words to parse before one arrives at the payoff. But if the branch is bushy, or if one branch is packed inside another, a left-branching structure can give the reader a headache. The most obvious examples are iterated possessives such as my mother’s brother’s wife’s father’s cousin. Left-branching trees are a hazard of headline writing. Here’s one that reported the death of a man who achieved fifteen minutes of fame in 1994 for hatching a plot to get Tonya Harding onto the US Olympic skating team by clubbing her main rival on the knee:

ADMITTED OLYMPIC SKATER NANCY KERRIGAN ATTACKER BRIAN SEAN GRIFFITH DIES

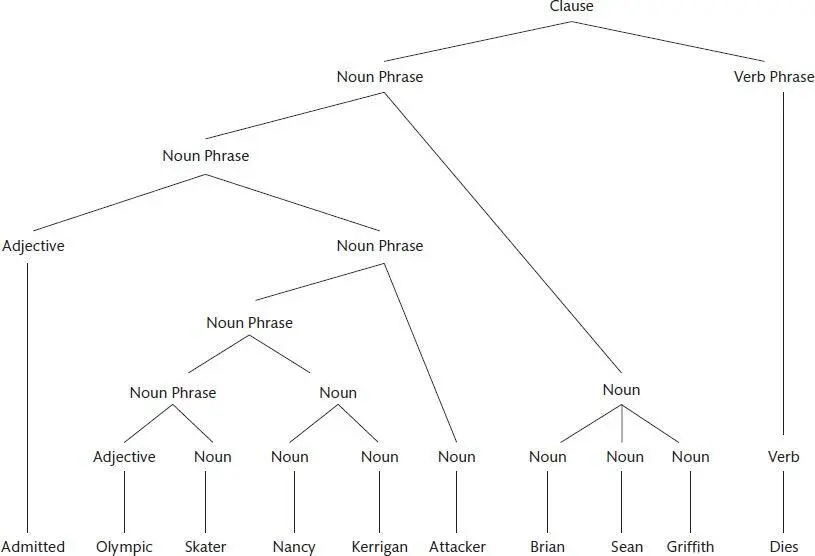

A blogger posted a commentary entitled “Admitted Olympic Skater Nancy Kerrigan Attacker Brian Sean Griffith Web Site Obituary Headline Writer Could Have Been Clearer.” The lack of clarity in the original headline was the result of its left-branching geometry: it has a ramified left branch (all the material before Dies ), which itself contains a ramified left branch (all the material before Brian Sean Griffith ), which in turn contains a ramified left branch (all the material before Attacker ): 19

Linguists call these constructions “noun piles.” Here are few others that have been spotted by contributors to the forum Language Log:

NUDE PIC ROW VICAR RESIGNS

TEXTING DEATH CRASH PEER JAILED

BEN DOUGLAS BAFTA RACE ROW HAIRDRESSER JAMES BROWN “SORRY”

FISH FOOT SPA VIRUS BOMBSHELL

CHINA FERRARI SEX ORGY DEATH CRASH

My favorite explanation of the difference in difficulty between flat, right-branching, and left-branching trees comes from Dr. Seuss’s Fox in Socks, who takes a flat clause with three branches, each containing a short right-branching clause, and recasts it as a single left-branching noun phrase: “When beetles fight these battles in a bottle with their paddles and the bottle’s on a poodle and the poodle’s eating noodles, they call this a muddle puddle tweetle poodle beetle noodle bottle paddle battle.”

As much of a battle as left-branching structures can be, they are nowhere near as muddled as center-embedded trees, those in which a phrase is jammed into the middle of a larger phrase rather than fastened to its left or right edge. In 1950 the linguist Robert A. Hall wrote a book called Leave Your Language Alone. According to linguistic legend, it drew a dismissive review entitled “Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone.” The author was invited to reply, and wrote a rebuttal called—of course—“Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone.”

Unfortunately, it’s only a legend; the recursive title was dreamed up by the linguist Robin Lakoff for a satire of a linguistics journal. 20But it makes a serious point: a multiply center-embedded sentence, though perfectly grammatical, cannot be parsed by mortal humans. 21Though I’m sure you can follow an explanation on why the string Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone has a well-formed tree, you could never recover it from the string. The brain’s sentence parser starts to thrash when faced with the successive leave s at the beginning, and it crashes altogether when it gets to the pile of alone s at the end.

Center-embedded constructions are not just linguistic in-jokes; they are often the diagnosis for what we sense as “convoluted” or “tortuous” syntax. Here is an example from a 1999 editorial on the Kosovo crisis (entitled “Aim Straight at the Target: Indict Milosevic”) by the senator and former presidential candidate Bob Dole: 22

The view that beating a third-rate Serbian military that for the third time in a decade is brutally targeting civilians is hardly worth the effort is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

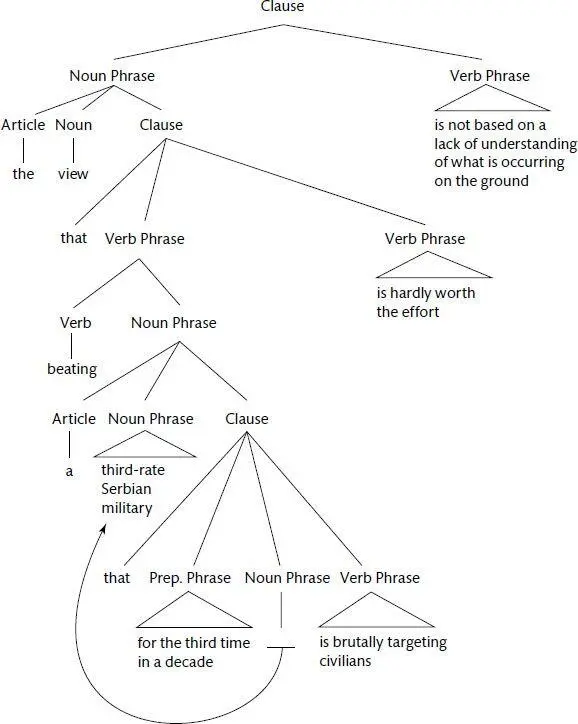

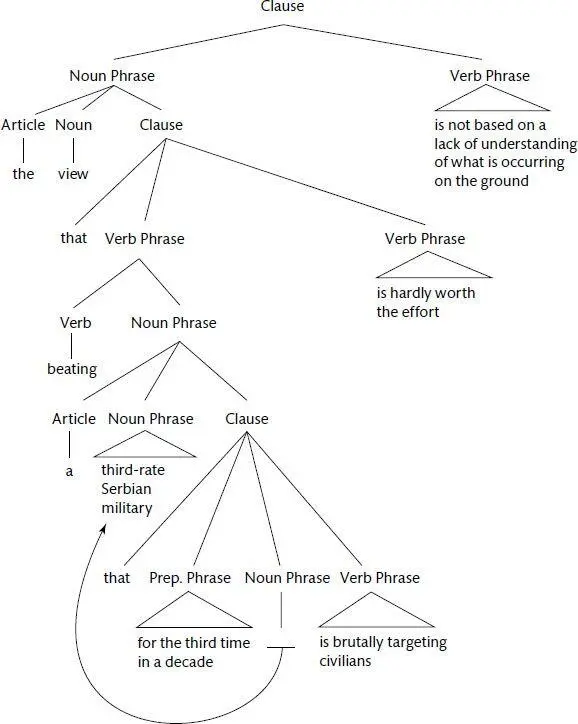

As with Leave Leave Leave Your Language Alone Alone Alone, this sentence ends bafflingly, with three similar phrases in a row: is brutally targeting civilians, is hardly worth the effort, is not based on a lack of understanding. Only with a tree diagram can you figure it out:

The first of the three is- phrases, is brutally targeting civilians, is the most deeply embedded one; it is part of a relative clause that modifies third-rate Serbian military . That entire phrase (the military that is targeting the civilians) is the object of the verb beating. That still bigger phrase (beating the military) is the subject of a sentence whose predicate is the second is- phrase, is hardly worth the effort. That sentence in turn belongs to a clause which spells out the content of the noun view. The noun phrase containing view is the subject of the third is -phrase, is not based on a lack of understanding.

In fact, the reader’s misery begins well before she plows into the pile of is- phrases at the end. Midway through the sentence, while she is parsing the most deeply embedded clause, she has to figure out what the third-rate Serbian military is doing, which she can only do when she gets to the gap before is brutally targeting civilians nine words later (the link between them is shown as a curved arrow). Recall that filling gaps is a chore which arises when a relative clause introduces a filler noun and leaves the reader uncertain about what role it is going to play until she finds a gap for it to fill. As she is waiting to find out, new material keeps pouring in ( for the third time in a decade ), making it easy for her to lose track of how to join them up.

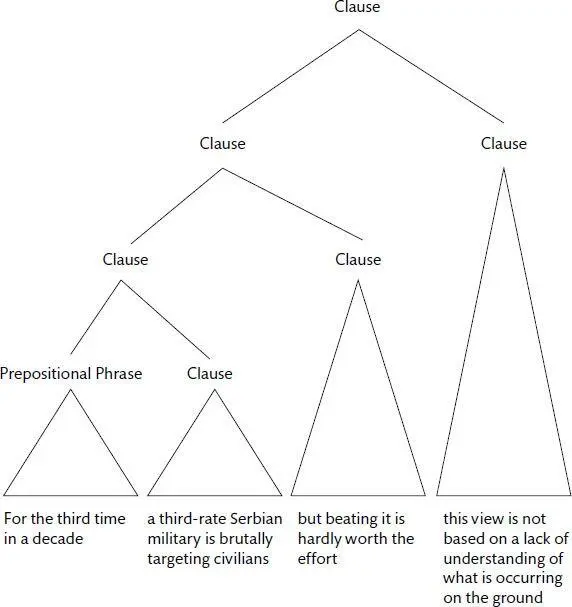

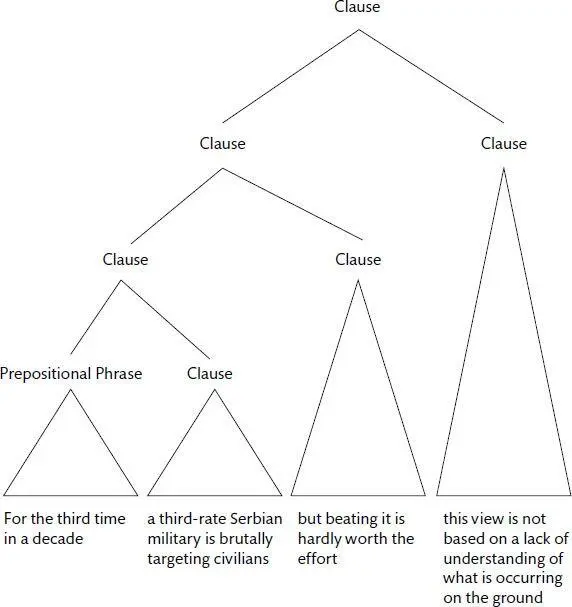

Can this sentence be saved? If you insist on keeping it as a single sentence, a good start is to disinter each embedded clause and place it side by side with the clause that contained it, turning a deeply center-embedded tree into a relatively flat one. This would give us For the third time in a decade, a third-rate Serbian military is brutally targeting civilians, but beating it is hardly worth the effort; this view is not based on a lack of understanding of what is occurring on the ground.

It’s still not a great sentence, but now that the tree is flatter one can see how to lop off entire branches and make them into separate sentences. Splitting in two (or three or four) is often the best way to tame a sentence that has grown unruly. In the following chapter, which is about sequences of sentences rather than individual sentences, we’ll see how to do that.

How does a writer manage to turn out such tortuous syntax? It happens when he shovels phrase after phrase onto the page in the order in which each one occurs to him. The problem is that the order in which thoughts occur to the writer is different from the order in which they are easily recovered by a reader. It’s a syntactic version of the curse of knowledge. The writer can see the links among the concepts in his internal web of knowledge, and has forgotten that a reader needs to build an orderly tree to decipher them from his string of words.

Читать дальше