In chapter 3 I mentioned two ways to improve your prose—showing a draft to someone else, and revisiting it after some time has passed—and both can allow you to catch labyrinthine syntax before inflicting it on your readers. There’s a third time-honored trick: read the sentence aloud. Though the rhythm of speech isn’t the same as the branching of a tree, it’s related to it in a systematic way, so if you stumble as you recite a sentence, it may mean you’re tripping on your own treacherous syntax. Reading a draft, even in a mumble, also forces you to anticipate what your readers will be doing as they understand your prose. Some people are surprised by this advice, because they think of the claim by speed-reading companies that skilled readers go directly from print to thought. Perhaps they also recall the stereotype from popular culture in which unskilled readers move their lips when they read. But laboratory studies have shown that even skilled readers have a little voice running through their heads the whole time. 23The converse is not true—you might zip through a sentence of yours that everyone else finds a hard slog—but prose that’s hard for you to pronounce will almost certainly be hard for someone else to comprehend.

Earlier I mentioned that holding the branches of a tree in memory is one of the two cognitive challenges in parsing a sentence. The other is growing the right branches, that is, inferring how the words are supposed to join up in phrases. Words don’t come with labels like “I’m a noun” or “I’m a verb.” Nor is the boundary where one phrase leaves off and the next one begins marked on the page. The reader has to guess, and it’s up to the writer to ensure that the guesses are correct. They aren’t always. A few years ago a member of a consortium of student groups at Yale put out this press release:

I’m coordinating a huge event for Yale University which is titled “Campus-Wide Sex Week.”

The week involves a faculty lecture series with topics such as transgender issues: where does one gender end and the other begin, the history of romance, and the history of the vibrator. Student talks on the secrets of great sex, hooking up, and how to be a better lover and a student panel on abstainance. … A faculty panel on sex in college with four professors. a movie film festival (sex fest 2002) and a concert with local bands and yale bands. …

The event is going to be huge and all of campus is going to be involved.

One recipient, the writer Ron Rosenbaum, commented, “One of my first thoughts on reading this was that before Yale (my beloved alma mater) had a Sex Week it ought to institute a gala Grammar and Spelling Week. In addition to ‘abstainance’ (unless it was a deliberate mistake in order to imply that ‘Yale puts the stain in abstinence’) there was that intriguing ‘faculty panel on sex in college with four professors,’ whose syntax makes it sound more illicit than it was probably intended to be.” 24

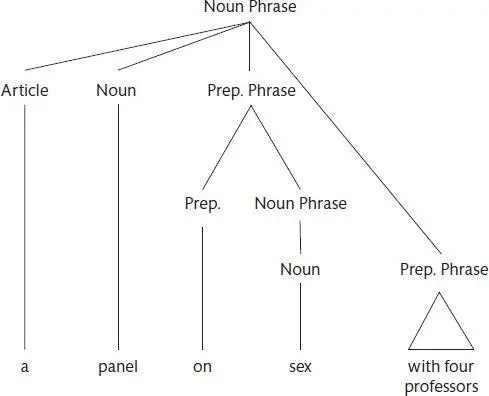

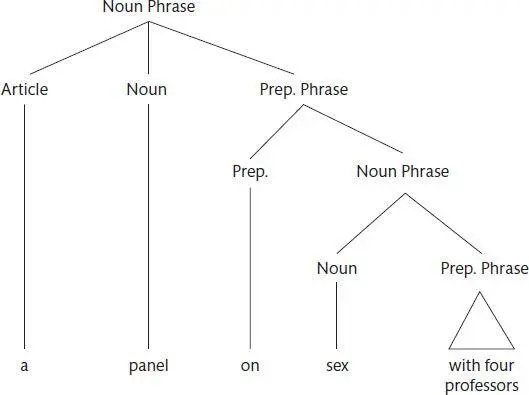

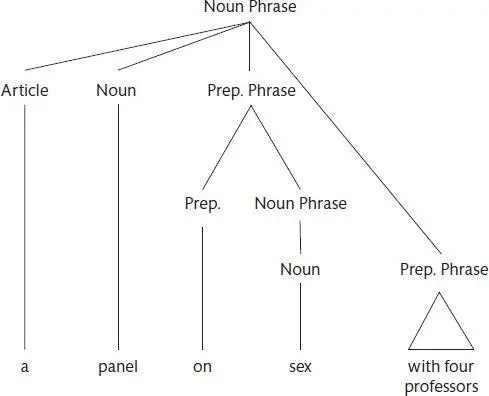

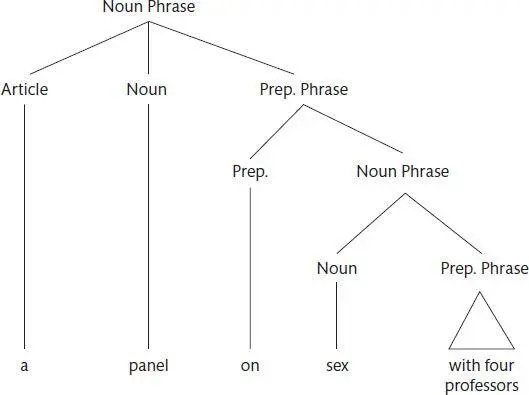

The student coordinator had blundered into the problem of syntactic ambiguity. In the simpler case of lexical ambiguity, an individual word has two meanings, as in the headlines SAFETY EXPERTS SAY SCHOOL BUS PASSENGERS SHOULD BE BELTED and NEW VACCINE MAY CONTAIN RABIES. In syntactic ambiguity, there may be no single word that is ambiguous, but the words can be interconnected into more than one tree. The organizer of Sex Week at Yale intended the first tree, which specifies a panel with four professors: Rosenbaum parsed it with the second tree, which specifies sex with four professors:

Syntactic ambiguities are the source of frequently emailed bloopers in newspaper headlines (LAW TO PROTECT SQUIRRELS HIT BY MAYOR), medical reports ( The young man had involuntary seminal fluid emission when he engaged in foreplay for several weeks ), classified ads ( Wanted: Man to take care of cow that does not smoke or drink ), church bulletins ( This week’s youth discussion will be on teen suicide in the church basement ), and letters of recommendation ( I enthusiastically recommend this candidate with no qualifications whatsoever ). 25 These Internet memes may seem too good to be true, but I’ve come across a few on my own, and colleagues have sent me others:

Prosecutors yesterday confirmed they will appeal the “unduly lenient” sentence of a motorist who escaped prison after being convicted of killing a cyclist for the second time.

THE PUBLIC VALUES FAILURES OF CLIMATE SCIENCE IN THE US

A teen hunter has been convicted of second-degree manslaughter for fatally shooting a hiker on a popular Washington state trail he had mistaken for a bear.

MANUFACTURING DATA HELPS INVIGORATE WALL STREET 26

THE TROUBLE WITH TESTING MANIA

For every ambiguity that is inadvertently funny or ironic, there must be thousands that are simply confusing. The reader has to scan the sentence several times to figure out which of two meanings the writer intended, or worse, she may come away with the wrong meaning without realizing it. Here are three I noticed in just a few days of reading:

The senator plans to introduce legislation next week that fixes a critical flaw in the military’s handling of assault cases. The measure would replace the current system of adjudicating sexual assault by taking the cases outside a victim’s chain of command. [Is it the new measure that takes the cases outside the chain of command, or is it the current system?]

China has closed a dozen websites, penalized two popular social media sites, and detained six people for circulating rumors of a coup that rattled Beijing in the middle of its worst high-level political crisis in years. [Did the coup rattle Beijing, or did rumors?]

Last month, Iran abandoned preconditions for resuming international negotiations over its nuclear programs that the West had considered unacceptable. [Were the preconditions unacceptable, or the negotiations, or the programs?]

And for every ambiguity that yields a coherent (but unintended) interpretation of the whole sentence, there must be thousands which trip up the reader momentarily, forcing her to backtrack and re-parse a few words. Psycholinguists call these local ambiguities “garden paths,” from the expression “to lead someone up the garden path,” that is, to mislead him. They have made an art form out of grammatical yet unparsable sentences: 27

The horse raced past the barn fell. [= “The horse that was raced (say, by a jockey) past the barn was the horse that fell.”]

The man who hunts ducks out on weekends.

Cotton clothing is made from is grown in Egypt.

Fat people eat accumulates.

The prime number few.

When Fred eats food gets thrown.

I convinced her children are noisy.

She told me a little white lie will come back to haunt me.

The old man the boat.

Have the students who failed the exam take the supplementary.

Most garden paths in everyday writing, unlike the ones in textbooks, don’t bring the reader to a complete standstill; they just delay her for a fraction of a second. Here are a few I’ve collected recently, with an explanation of what led me astray in each case:

During the primary season, Mr. Romney opposed the Dream Act, proposed legislation that would have allowed many young illegal immigrants to remain in the country. [Romney opposed the Act and also proposed some legislation? No, the Act is a piece of legislation that had been proposed.]

Those who believe in the necessity of nuclear weapons as a deterrent tool fundamentally rely on the fear of retaliation, whereas those who don’t focus more on the fear of an accidental nuclear launch that might lead to nuclear war. [Those who don’t focus? No, those who don’t believe in the necessity of a nuclear deterrent.]

Читать дальше