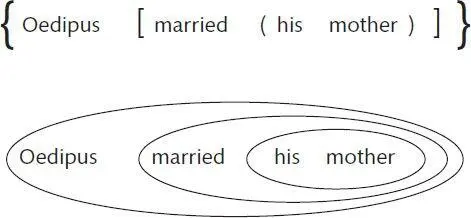

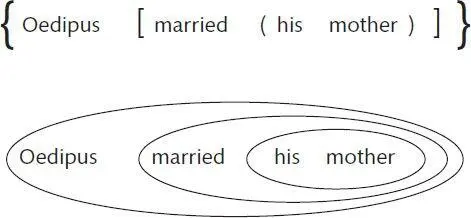

The tree, of course, is only a metaphor. What it captures is that adjacent words are grouped into phrases, that the phrases are embedded inside larger phrases, and that the arrangement of words and phrases may be used to recover the relationships among the characters in the speaker’s mind. A tree is simply an easy way to display that design on a page. The design could just as accurately be shown with a series of braces and brackets, or with a Venn diagram:

Regardless of the notation, appreciating the engineering design behind a sentence—a linear ordering of phrases which conveys a gnarly network of ideas—is the key to understanding what you are trying to accomplish when you compose a sentence. And that, in turn, can help you understand the menu of choices you face and the things that are most likely to go wrong.

The reason that the task is so challenging is that the main resource that English syntax makes available to writers—left-to-right ordering on a page—has to do two things at once. It’s the code that the language uses to convey who did what to whom. But it also determines the sequence of early-to-late processing in the reader’s mind. The human mind can do only a few things at a time, and the order in which information comes in affects how that information is handled. As we’ll see, a writer must constantly reconcile the two sides of word order: a code for information, and a sequence of mental events.

Let’s begin with a closer look at the code of syntax itself, using the tree for the Oedipus sentence as an example. 5Working upward from the words at the bottom, we see that every word is labeled with a grammatical category. These are the “parts of speech” that should be familiar even to people who were educated after the 1960s:

Nouns (including pronouns)

man, play, Sophocles, she, my

Verbs

marry, write, think, see, imply

Prepositions

in, around, underneath, before, until

Adjectives

big, red, wonderful, interesting, demented

Adverbs

merrily, frankly, impressively, very, almost

Articles and other determinatives

the, a, some, this, that, many, one, two, three

Coordinators

and, or, nor, but, yet, so

Subordinators

that, whether, if, to

Each word is slotted into a place in the tree according to its category, because the rules of syntax don’t specify the order of words but rather the order of categories. Once you have learned that in English the article comes before the noun, you don’t have to relearn that order every time you acquire a new noun, such as hashtag, app, or MOOC . If you’ve seen one noun, you’ve pretty much seen them all. There are, to be sure, subcategories of the noun category like proper nouns, common nouns, mass nouns, and pronouns, which indulge in some additional pickiness about where they appear, but the principle is the same: words within a subcategory are interchangeable, so that if you know where the subcategory may appear, you know where every word in that subcategory may appear.

Let’s zoom in on one of the words, married. Together with its grammatical category, verb, we see a label in parentheses for its grammatical function, in this case, head. A grammatical function identifies not what a word is in the language but what it does in that particular sentence: how it combines with the other words to determine the sentence’s meaning.

The “head” of a phrase is the little nugget which stands for the whole phrase. It determines the core of the phrase’s meaning: in this case married his mother is a particular instance of marrying. It also determines the grammatical category of the phrase: in this case it is a verb phrase, a phrase built around a verb. A verb phrase is a string of words of any length which fills a particular slot in a tree. No matter how much stuff is packed into the verb phrase— married his mother; married his mother on Tuesday; married his mother on Tuesday over the objections of his girlfriend —it can be inserted into the same position in the sentence as the phrase consisting solely of the verb married. This is true of the other kinds of phrases as well: the noun phrase the king of Thebes is built around the head noun king, it refers to an example of a king, and it can go wherever the simpler phrase the king can go.

The extra stuff that plumps out a phrase may include additional grammatical functions which distinguish the various roles in the story identified by the head. In the case of marrying, the dramatis personae include the person being married and the person doing the marrying. (Though marrying is really a symmetrical relationship—if Jack married Jill, then Jill married Jack—let’s assume for the sake of the example that the male takes the initiative in marrying the female.) The person being married in this sentence is, tragically, the referent of his mother, and she is identified as the one being married because the phrase has the grammatical function “object,” which in English is the noun phrase following the verb. The person doing the marrying, referred to by the one-word phrase Oedipus, has the function “subject.” Subjects are special: all verbs have one, and it sits outside the verb phrase, occupying one of the two major branches of the clause, the other being the predicate. Still other grammatical functions can be put to work in identifying other roles. In Jocasta handed the baby to the servant, the phrase the servant is an oblique object, that is, the object of a preposition. In Oedipus thought that Polybus was his father, the clause that Polybus was his father is a complement of the verb thought .

Languages also have grammatical functions whose job is not to distinguish the cast of characters but to pipe up with other kinds of information. Modifiers can add comments on the time, place, manner, or quality of a thing or an action. In this sentence we have the phrase In Sophocles’ play as a modifier of the clause Oedipus married his mother. Other examples of modifiers include the underlined words in the phrases walks on four legs, swollen feet, met him on the road to Thebes, and the shepherd whom Oedipus had sent for.

We also find that the nouns play and mother are preceded by the words Sophocles’ and his, which have the function “determiner.” A determiner answers the question “Which one?” or “How many?” Here the determiner role is filled by what is traditionally called a possessive noun (though it is really a noun marked for genitive case, as I will explain). Other common determiners include articles, as in the cat and this boy; quantifiers, as in some nights and all people; and numbers, as in sixteen tons.

If you are over sixty or went to private school, you may have noticed that this syntactic machinery differs in certain ways from what you remember from Miss Thistlebottom’s classroom. Modern grammatical theories (like the one in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, which I use in this book) distinguish grammatical categories like noun and verb from grammatical functions like subject, object, head, and modifier. And they distinguish both of these from semantic categories and roles like action, physical object, possessor, doer, and done-to, which refer to what the referents of the words are doing in the world. Traditional grammars tend to run the three concepts together.

Читать дальше