Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He was, to put it mildly, very good at it. He built bridges and viaducts across impossible defiles, railway concourses of stunning expansiveness, and other grand and challenging structures that continue to impress and inspire, including, in 1884, one of the trickiest of all, the internal supporting skeleton for the Statue of Liberty. Everybody thinks of the Statue of Liberty as the work of the sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi, and it is of course his design. But without ingenious interior engineering to hold it up, the Statue of Liberty is merely a hollow structure of beaten copper barely one-tenth of an inch thick. That’s about the thickness of a chocolate Easter bunny—but an Easter bunny 151 feet high, which must stand up to wind, snow, driving rain, and salt spray; the expansion and contraction of metal in sun and cold; and a thousand other rude, daily physical assaults.

None of these challenges had ever been faced by an engineer before, and Eiffel solved them in the neatest possible way: by creating a skeleton of trusses and springs on which the copper skin is worn like a suit of clothes. Although he wasn’t thinking of what this technique could do for more conventional buildings, it marked the invention of curtain-wall construction, the most important building technique of the twentieth century—the form of construction that made skyscrapers possible. (The builders of Chicago’s early skyscrapers also independently invented curtain-wall construction, but Eiffel got there first.) The ability of the metal skin to twist under pressure neatly anticipated the design of airplane wings long before anyone was seriously thinking about airplanes at all. So the Statue of Liberty is quite a piece of work, but because all that ingenuity is underneath Liberty’s gowns, almost no one appreciates it.

Eiffel was not a vain man, but in his next big project he made sure no one would fail to appreciate his role in its construction by creating something that was nothing but skeleton. The event that brought it into being was the Paris Exposition of 1889.

As is usual with these things, the organizers wanted an iconic centerpiece and invited proposals. A hundred or so were submitted, including a design for a nine-hundred-foot-high guillotine, to commemorate France’s unrivaled contribution to decapitation. For many that was scarcely more preposterous than Eiffel’s winning entry. Large numbers of Parisians could not see the point of placing an enormous functionless derrick in the middle of the city.

The Eiffel Tower wasn’t just the largest thing that anyone had ever proposed to build, it was the largest completely useless thing. It wasn’t a palace or burial chamber or place of worship. It didn’t even commemorate a fallen hero. Eiffel gamely insisted that his tower would have many practical applications—that it would make a terrific military lookout and that one could do useful aeronautical and meteorological experiments from its upper reaches—but eventually even he admitted that mostly he wished to build it simply for the slightly strange pleasure of making something really quite enormous.

Many people loathed it, especially artists and intellectuals. A group of notables that included Alexandre Dumas, Émile Zola, Paul Verlaine, and Guy de Maupassant submitted a long, rather overexcited letter protesting at “the deflowering of Paris” and arguing that “when foreigners come to see our exhibition they will cry out in astonishment, ‘What! This is the atrocity which the French have created to give us an idea of their boasted taste!’ ” The Eiffel Tower, they continued, was “the grotesque, mercenary invention of a machine builder.” Eiffel accepted the insults with cheerful equanimity and merely pointed out that one of the outraged signatories of the petition, the architect Charles Garnier, was in fact a member of the commission that had approved the tower in the first place.

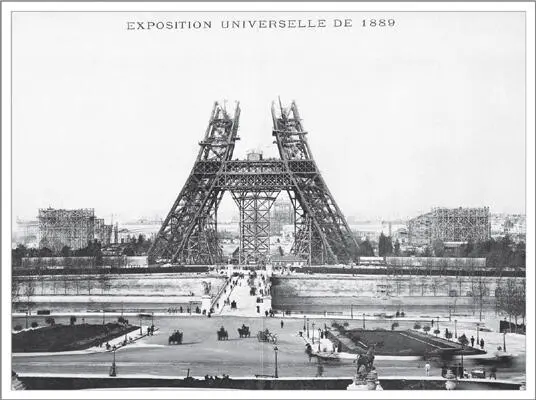

Eiffel’s Tower under construction, Paris, 1888 (photo credit 10.1)

In its finished state, the Eiffel Tower seems so singular and whole, so couldn’t-be-otherwise, that we have to remind ourselves that it is an immensely complex assemblage, a fretwork of eighteen thousand intricately fitted parts, which come together only because of an immense amount of the very cleverest thought. Consider just the first 180 feet of the structure, up to the first platform—already the height of a ten- or twelve-story building. Up to that height the legs lean steeply inward at an angle of 54 degrees. They would clearly fall over if they weren’t braced by the platform. The platform just as clearly couldn’t be up there without the four legs underneath to support it. The parts work flawlessly when brought together, but until they are brought together they cannot work at all. Eiffel’s first challenge, therefore, was to devise some way to brace four immensely tall and heavy legs, each straining to topple inward; then, at the right moment, be able to ease them into position so that all four came together at exactly the right points to support a large and very heavy platform. An incorrect alignment of as little as one-tenth of one degree would have put any leg out by a foot and a half—far more than could be corrected without taking everything down and starting all over again. Eiffel effected the delicate operation by anchoring each leg in a giant container of sand, like a foot in a large boot, which held them securely during construction. Then, when work on them was complete, the legs could be eased into position by letting sand out of the boxes in a carefully controlled manner. The system worked perfectly.

But that was only the start of things. Above the first platform came another eight hundred feet of iron framework made from fifteen thousand mostly large, unwieldy pieces, all of which had to be swung into place at increasingly challenging heights. Tolerances in some places were as little as one-tenth of a millimeter. Some observers were convinced that the tower couldn’t support its own weight. A professor of mathematics filled reams of paper with calculations and concluded that when the tower was two-thirds up, the legs would splay and the whole would collapse in a thunderous fury, crushing the neighborhood below. In fact, the Eiffel Tower is pretty light at just 9,500 tons—it is mostly air, after all—and needed foundations just seven feet deep to support its weight.

More time was spent designing the Eiffel Tower than building it. Erection took under two years and came in well under budget. Just 130 workers were needed on-site, and none died in its construction—a magnificent achievement for a project this large in that age. Until the erection of the Chrysler Building in New York in 1930, it would be the tallest structure in the world. Although by 1889 steel was displacing iron everywhere, Eiffel rejected it because he had always worked in iron and didn’t feel comfortable with steel. So there is a certain irony in the thought that the greatest edifice ever built of iron was also the last.

The Eiffel Tower was the most striking and imaginative large structure in the world in the nineteenth century, and perhaps the greatest structural achievement, too, but it wasn’t the most expensive building of its century or even of its year. At the very moment that the Eiffel Tower was rising in Paris, two thousand miles away, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in North Carolina, an even more expensive structure was going up—a private residence on rather a grand scale. It would take more than twice as long to complete as the Eiffel Tower, employ four times as many workers, cost three times as much to build, and was intended to be lived in for just a few months a year by one man and his mother. Called Biltmore, it was (and remains) the largest private house ever built in North America. Nothing can say more about the shifting economics of the late nineteenth century than that the residents of the New World were now building houses greater than the greatest monuments of the Old.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.