Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Just two materials seemed to be impervious to the insult of corrosive acids. One was a remarkable artificial stone known as Coade stone (named after Eleanor Coade, who owned the factory that made it). Coade stone was immensely popular and was used by every leading architect from about 1760 to 1830. It was practically indestructible and could be shaped into any kind of ornamental object—friezes, arabesques, capitals, modillions, or any other decorative thing that would normally be carved. The best known Coade object is the large lion on Westminster Bridge near the Houses of Parliament, but Coade stone can be found all over—at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, the Tower of London, on the tomb of Captain Bligh in the churchyard of St. Mary-at-Lambeth, London.

Coade stone looks and feels exactly like worked stone, and weathers as hard as the hardest stone, but it isn’t stone at all. It is, surprisingly, a ceramic. Ceramics are baked clay. Depending on the type of clay and how intensely they are fired, they yield one of three different materials: earthenware, stoneware, or porcelain. Coade stone is a type of stoneware, but an especially hard and durable type. Most Coade stone is so resistant to weather and pollution that it looks almost brand-new even after nearly two and a half centuries of exposure to the elements.

Considering its ubiquity and remarkable characteristics, surprisingly little is known about Coade stone and its eponymous maker. Where and when it was invented, how Eleanor Coade became involved with it, and why the firm came to a sudden end sometime in the late 1830s are all matters that have failed to excite much scholarly interest. Coade receives only half a dozen paragraphs in the Dictionary of National Biography , and the only full-scale history of her and her firm was a work self-published by the historian Alison Kelly in 1999.

What can be said for certain is that Eleanor Coade was the daughter of a failed businessman from Exeter, who came to London in about 1760 and ran a successful business selling linens. Toward the end of the decade she met one Daniel Pincot, who was already engaged in the manufacture of artificial stone. They opened a factory on the south side of the Thames about where Waterloo Station stands today and began producing an unusually high-grade material. Coade is often credited as its inventor, but it seems more likely that Pincot had the method and she the money. In any case, Pincot left the firm after just two years and was heard from no more. Eleanor Coade ran the business very successfully for fifty-two years until her death at the age of eighty-eight in 1821—an especially remarkable achievement for a woman in the eighteenth century. She never married. Whether she was sweet and beloved or a raging harridan we have no idea. All that can be said is that the Coade company’s sales dwindled without her. Eventually, the firm went under, but so quietly that no one is sure now when exactly it ceased production.

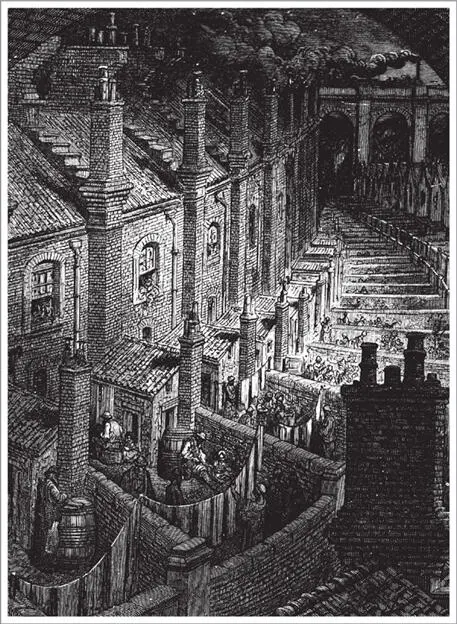

The back streets of Victorian London, as illustrated by Gustave Doré (photo credit 9.1)

There is an enduring myth that the secret of Coade stone died with Eleanor Coade. In fact, the process has been reproduced experimentally on at least two occasions. Nothing is stopping people from making it commercially now. The only reason it isn’t made is that nobody bothers.

Coade stone could only ever be used for incidental decorative purposes. Fortunately, there was one venerable building material that also stood up to pollution very well: brick. Pollution was the making of modern brick, though several other timely factors helped. The development of canals made it economical to ship bricks over considerable distances. The invention of the Hoffmann kiln (named for Friedrich Hoffmann, its German inventor) allowed bricks to be produced continuously, and thus more cheaply, along a sort of production line. The removal of the brick tax in 1850 reduced costs further still. The biggest spur of all was simply Britain’s phenomenal growth in the nineteenth century—the growth of cities, of industry, of people needing housing. In the lifetime of Queen Victoria, London’s population went from one million to nearly seven million, and newly industrialized cities like Manchester, Leeds, and Bradford had growth rates greater still. Overall, the number of houses in Britain quadrupled in the century, and the new housing stock overwhelmingly was of brick, as were most of the mills, chimneys, railway stations, sewers, schools, churches, offices, and other new infrastructure that leaped into being in that frantically busy age. Brick was too versatile and economical to resist. It became the default building material of the Industrial Revolution.

According to one estimate, more bricks were laid in Britain in the Victorian period than in all of previous history together. The growth of London meant the spread of suburbs of more or less identical brick houses—mile after mile of “dreary repetitious mediocrity,” in Disraeli’s bleak description. The Hoffmann kiln had much to answer for here, since it introduced absolute uniformity of size, color, and appearance to bricks. Buildings made of the new-style bricks had much less subtlety and character than buildings of earlier eras, but they were much cheaper, and there has hardly ever been a time in the conduct of human affairs when cheapness didn’t triumph.

There was just one problem with brick that became increasingly apparent as the century wore on and building space grew constrained. Bricks are immensely heavy, and you can’t make really tall buildings with them—not that people didn’t try. The tallest brick building ever built was the sixteen-story Monadnock Building, a general-purpose office building erected in Chicago in 1893 and designed shortly before his death by the architect John Root of the famous firm of Burnham and Root. The Monadnock Building still stands, and is an extraordinary edifice. Such is its weight that the walls at street level are six feet thick, making the ground floor—normally the most welcoming part of a building—into a dark and forbidding vault.

The Monadnock Building would be exceptional anywhere, but it is particularly so in Chicago, where the Earth is essentially a large sponge. Chicago is built on mud flats: anything heavy deposited on Chicago soil wants to sink—and, in the early days, buildings pretty generally did sink. Most architects allowed for a foot or so of settling in Chicago’s soils. Sidewalks were built with a severe slant, running upward from the curb to the building. The hope was that as the building settled, the sidewalk would come down with it into a position of perfect horizontality. In practice, it seldom did.

To ameliorate the sinking problem, nineteenth-century architects developed a technique of constructing a “raft” on which the building could stand, rather as a surfer stands on a surfboard. The raft under the Monadnock Building extends eleven feet beyond the building in every direction, but even with the raft, the building sank almost two feet after construction—something you really don’t want a sixteen-story building to do. It is a testimony to the skills of John Root that the building still stands. Many others weren’t so fortunate. A government office block called the Federal Building, constructed at a staggering cost of $5 million in 1880, took on such a swift and dangerous pitch that it didn’t last two decades. Many other smaller buildings had similarly abbreviated lives.

What architects needed was some kind of lighter and more flexible building material, and for a long time it seemed that that would be the one Joseph Paxton first brought to large-scale fame with the Crystal Palace: iron.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.