Bill Bryson

Shakespeare: The World as Stage

***

Chapter One. In Search of William Shakespeare

BEFORE HE CAME INTO a lot of money in 1839, Richard Plantagenet Temple Nugent Brydges Chandos Grenville, second Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, led a largely uneventful life.

He sired an illegitimate child in Italy, spoke occasionally in the Houses of Parliament against the repeal of the Corn Laws, and developed an early interest in plumbing (his house at Stowe, in Buckinghamshire, had nine of the first flush toilets in England), but otherwise was distinguished by nothing more than his glorious prospects and many names. But after inheriting his titles and one of England ’s great estates, he astonished his associates, and no doubt himself, by managing to lose every penny of his inheritance in just nine years through a series of spectacularly unsound investments.

Bankrupt and humiliated, in the summer of 1848 he fled to France, leaving Stowe and its contents to his creditors. The auction that followed became one of the great social events of the age. Such was the richness of Stowe’s furnishings that it took a team of auctioneers from the London firm of Christie and Manson forty days to get through it all.

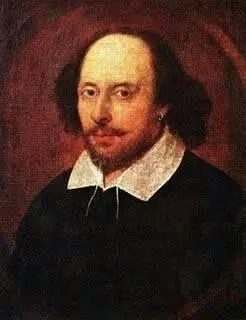

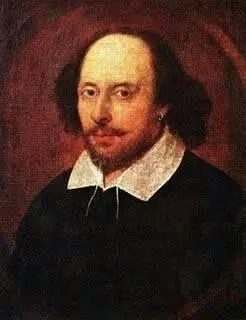

Among the lesser-noted disposals was a dark oval portrait, twenty-two inches high by eighteen wide, purchased by the Earl of Ellesmere for 355 guineas and known ever since as the Chandos portrait. The painting had been much retouched and was so blackened with time that a great deal of detail was (and still is) lost. It shows a balding but not unhandsome man of about forty who sports a trim beard. In his left ear he wears a gold earring. His expression is confident, serenely rakish. This is not a man, you sense, to whom you would lightly entrust a wife or grown daughter.

Although nothing is known about the origin of the painting or where it was for much of the time before it came into the Chandos family in 1747, it has been said for a long time to be of William Shakespeare. Certainly it looks like William Shakespeare-but then really it ought to, since it is one of the three likenesses of Shakespeare from which all other such likenesses are taken.

In 1856, shortly before his death, Lord Ellesmere gave the painting to the new National Portrait Gallery in London as its founding work. As the gallery’s first acquisition, it has a certain sentimental prestige, but almost at once its authenticity was doubted. Many critics at the time thought the subject was too dark-skinned and foreign looking-too Italian or Jewish-to be an English poet, much less a very great one. Some, to quote the late Samuel Schoenbaum, were disturbed by his “wanton” air and “lubricious” lips. (One suggested, perhaps a touch hopefully, that he was portrayed in stage makeup, probably in the role of Shylock.)

“Well, the painting is from the right period-we can certainly say that much,” Dr. Tarnya Cooper, curator of sixteenth-century portraits at the gallery, told me one day when I set off to find out what we could know and reasonably assume about the most venerated figure of the English language. “The collar is of a type that was popular between about 1590 and 1610, just when Shakespeare was having his greatest success and thus most likely to sit for a portrait. We can also tell that the subject was a bit bohemian, which would seem consistent with a theatrical career, and that he was at least fairly well to do, as Shakespeare would have been in this period.”

I asked how she could tell these things.

“Well, the earring tells us he was bohemian,” she explained. “An earring on a man meant the same then as it does now-that the wearer was a little more fashionably racy than the average person. Drake and Raleigh were both painted with earrings. It was their way of announcing that they were of an adventurous disposition. Men who could afford to wore a lot of jewelry back then, mostly sewn into their clothes. So the subject here is either fairly discreet, or not hugely wealthy. I would guess probably the latter. On the other hand, we can tell that he was prosperous-or wished us to think he was prosperous-because he is dressed all in black.”

She smiled at my look of puzzlement. “It takes a lot of dye to make a fabric really black. Much cheaper to produce clothes that were fawn or beige or some other lighter color. So black clothes in the sixteenth century were nearly always a sign of prosperity.”

She considered the painting appraisingly. “It’s not a bad painting, but not a terribly good one either,” she went on. “It was painted by someone who knew how to prime a canvas, so he’d had some training, but it is quite workaday and not well lighted. The main thing is that if it is Shakespeare, it is the only portrait known that might have been done from life, so this would be what William Shakespeare really looked like-if it is William Shakespeare.”

And what are the chances that it is?

“Without documentation of its provenance we’ll never know, and it’s unlikely now, after such a passage of time, that such documentation will ever turn up.”

And if not Shakespeare, who is it?

She smiled. “We’ve no idea.”

If the Chandos portrait is not genuine, then we are left with two other possible likenesses to help us decide what William Shakespeare looked like. The first is the copperplate engraving that appeared as the frontispiece of the collected works of Shakespeare in 1623-the famous First Folio.

The Droeshout engraving, as it is known (after its artist, Martin Droeshout), is an arrestingly-we might almost say magnificently-mediocre piece of work. Nearly everything about it is flawed. One eye is bigger than the other. The mouth is curiously mispositioned. The hair is longer on one side of the subject’s head than the other, and the head itself is out of proportion to the body and seems to float off the shoulders, like a balloon. Worst of all, the subject looks diffident, apologetic, almost frightened-nothing like the gallant and confident figure that speaks to us from the plays.

Droeshout (or Drossaert or Drussoit, as he was sometimes known in his own time) is nearly always described as being from a family of Flemish artists, though in fact the Droeshouts had been in England for sixty years and three generations by the time Martin came along. Peter W. M. Blayney, the leading authority on the First Folio, has suggested that Droeshout, who was in his early twenties and not very experienced when he executed the work, may have won the commission not because he was an accomplished artist but because he owned the right piece of equipment: a rolling press of the type needed for copperplate engravings. Few artists had such a device in the 1620s.

Despite its many shortcomings, the engraving comes with a poetic endorsement from Ben Jonson, who says of it in his memorial to Shakespeare in the First Folio:

O, could he but have drawne his wit

As well in brasse, as he hath hit

His face, the Print would then surpasse

All that was ever writ in brasse.

It has been suggested, with some plausibility, that Jonson may not actually have seen the Droeshout engraving before penning his generous lines. What is certain is that the Droeshout portrait was not done from life: Shakespeare had been dead for seven years by the time of the First Folio.

That leaves us with just one other possible likeness: the painted, life-size statue that forms the centerpiece of a wall monument to Shakespeare at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, where he is buried. Like the Droeshout, it is an indifferent piece of work artistically, but it does have the merit of having been seen and presumably passed as satisfactory by people who knew Shakespeare. It was executed by a mason named Gheerart Janssen, and installed in the chancel of the church by 1623-the same year as Droeshout’s portrait. Janssen lived and worked near the Globe Theatre in Southwark in London and thus may well have seen Shakespeare in life-though one rather hopes not, as the Shakespeare he portrays is a puffy-faced, self-satisfied figure, with (as Mark Twain memorably put it) the “deep, deep, subtle, subtle expression of a bladder.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу