Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Fortunately, matters soon calmed down and a little illumination was allowed into people’s lives—just enough to stop most of the carnage—but it was a salutary reminder of how used to abundant illumination the world had grown.

We forget just how painfully dim the world was before electricity. A candle—a good candle—provides barely a hundredth of the illumination of a single 100-watt lightbulb.* Open your refrigerator door and you summon forth more light than the total amount enjoyed by most households in the eighteenth century. The world at night for much of history was a very dark place indeed.

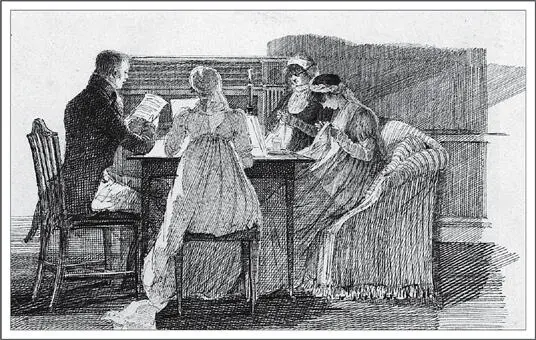

Occasionally we can see into the dimness, as it were, when we find descriptions of what was considered sumptuous, as when a guest at a Virginia plantation, Nomini Hall, marveled in his diary how “luminous and splendid” the dining room was during a banquet because seven candles were burning—four on the table and three elsewhere in the room. To him this was a blaze of light. At about the same time, across the ocean in England, a gifted amateur artist named John Harden left a charming set of drawings showing family life at his home, Brathay Hall in Westmorland. What is striking is how little illumination the family expected or required. A typical drawing shows four members sitting companionably at a table sewing or reading by the light of a single candle, and there is no sense of hardship or deprivation, and certainly no sign of the desperate postures of people trying to get a tiny bit of light to fall more productively on a page or piece of embroidery. A Rembrandt drawing, Student at a Table by Candlelight , is actually much closer to the reality. It shows a youth sitting at a table, all but lost in a depth of shadow and gloom that a single candle on the wall beside him cannot begin to penetrate. Yet he has a newspaper. The fact is that people put up with dim evenings because they knew no other kind.

Reading by candlelight, by John Harden (photo credit 6.1)

The widespread belief that people in the pre-electric world went to bed at nightfall seems to be based entirely on the presumption that anyone deprived of robust illumination would be driven by frustration to retire. In fact, it appears that most people didn’t retire terribly early—nine or ten o’clock seems to have been standard for most people in the days before electricity, and for some, particularly in cities, it was even later. For those who could control their working hours, bedtimes and rising times were at least as variable then as now and appear to have had little to do with the amount of light available. In one of his diary entries, Samuel Pepys records rising at four in the morning, but in another he records going to bed at four in the morning. The writer and lexicographer Samuel Johnson famously stayed abed till noon if he could; generally he could. The writer Joseph Addison routinely rose at three on summer mornings (and sometimes even earlier), but not till eleven in winter. There certainly seems to have been no rush to bring the day to a close. Visitors to eighteenth-century London often noted that the shops were open till ten at night, and clearly there would be no shops without shoppers. When guests were present, it was usual to serve supper at ten and for company to stay till midnight or so. Including conversation beforehand and music after, a dinner gathering could last for seven hours or more. Balls often went on until two or three in the morning, at which time a supper would be served. People were so keen to go out and stay up that they didn’t let much get in their way. In 1785 a Louisa Stewart wrote to her sister that the French ambassador suffered “a stroke of the palsy yesterday,” yet guests turned up at his house that night anyway “and played at faro, etc., as if he had not been dying in the next room. We are a curious people.”

Getting around outside after dark was hard. On the darkest nights it was not uncommon for the stumbling pedestrian to “run his Head against a Post” or suffer some other painful surprise. People had to grope their way through the darkness, although in some cases they simply groped: lighting in London was still so poor in 1763 that James Boswell was able to have sex with a prostitute on Westminster Bridge—hardly the most private of trysting places. Darkness also meant danger. Thieves were at large everywhere, and as one London authority noted in 1718, people were often reluctant to go out at night for fear that “they may be blinded, knocked down, cut or stabbed.” To avoid smacking into the unyielding, or being waylaid by brigands, people often secured the services of linkboys—so called because they carried torches known as links made from stout lengths of rope soaked in resin or some other combustible material—to see them home. Unfortunately, the linkboys themselves couldn’t always be trusted and sometimes led their customers into back alleys where they or their confederates relieved the hapless customers of money and silken items.

Even after gaslights became widely available for city streets in the mid-nineteenth century, by modern standards it was still a pretty murky world after nightfall. The very brightest gas streetlamps provided less light than a modern 25-watt bulb. Moreover they were distantly spaced. Generally, at least thirty yards of darkness lay between each, but on some roads—the King’s Road through London’s Chelsea, for instance—they were seventy yards apart; thus, they didn’t so much light the way as provide distant points of brightness to aim for. Yet gas lamps held out for a surprisingly long time in some quarters. As late as the 1930s, almost half of London streets were still lit by gas.

If anything drove people to bed early in the pre-electric world, it was not boredom but exhaustion. Many people worked immensely long hours. The Statute of Artificers of 1563 laid down that all artificers (craftsmen) and laborers “must be and continue at their work, at or before five of the clock in the morning, and continue at work, and not depart, until between seven and eight of the clock at night”—giving an eighty-four-hour workweek. At the same time, it is worth bearing in mind that a typical London theater like Shakespeare’s Globe could hold two thousand people (about 1 percent of London’s population), of whom a great part were working people, and that there were, moreover, several theaters in operation at any time, as well as alternative entertainments like bearbaiting and cockfighting. So, whatever the statutes may have decreed, it is apparent that on any given day several thousand working Londoners patently were not at their workbenches but were out having a good time.

What unquestionably consolidated long working hours was the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the factory system. In factories, workers were expected to be at their places from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. on weekdays and from 7:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. on Saturdays, but during the busiest periods of the year—what were known as “brisk times”—they could be kept at their machines from 3:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m.—a nineteen-hour day. Until the Factory Act of 1833, children as young as seven were required to work as long as adults. In such circumstances, not surprisingly, people ate and slept when they could.

The rich kept gentler hours. Writing of country life in 1768, Fanny Burney noted: “We breakfast always at ten, and rise as much before as we please; we dine precisely at two, drink tea about six and sup exactly at nine.” Her routine is echoed in countless diaries and letters from others of her class. “I will give an account of one day and then you will see every day,” a young correspondent wrote to Edward Gibbon in about 1780. Her day, she wrote, began at nine, and breakfast was at ten. “And then about 11 I play on the harpsichord, or I draw; at 1 I translate and 2 walk out again, 3 I generally read, and 4 we go to dine, after dinner we play at backgammon, we drink tea at 7, and I work or play on the piano till 10, when we have our little bit of supper and 11, we go to bed.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.