Bill Bryson - At Home

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - At Home» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:At Home

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

At Home: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «At Home»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

At Home — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «At Home», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He died in 1881. His written histories barely outlived him, but his personal history goes on and on, thanks in very large part to the exceptionally voluminous correspondence that he and his wife left behind—enough to fill thirty volumes of close-printed text. Thomas Carlyle would no doubt be astonished and dismayed today to learn that his histories are largely unread, but that he is known now for the minutiae of his daily life, including decades of petty moans about servants. The irony, of course, is that employing a succession of thankless servants is what gave him and his wife the leisure to write all those letters.

Much of this had always been thus. Like the Carlyles, but nearly two centuries earlier, Samuel Pepys and his wife, Elizabeth, had a seemingly endless string of servants during the nine and a half years in which Pepys wrote his famous diary, and perhaps little wonder since he spent a good deal of his time pawing the females and beating the boys—though, come to that, he beat the girls quite a lot, too. Once he took a broom to a servant named Jane “and basted her till she cried extremely.” Her crime was that she was untidy. Pepys kept a boy whose principal function seems to have been to give him something convenient to hit—“with a cane or a birch or a whip or a rope’s end, or even a salted eel,” as the historian Liza Picard puts it.

Pepys was also a great one for dismissing servants. One was sacked for uttering “some sawcy words,” another for being a gossip. One was given new clothes upon arrival, but ran off that night; when she was caught, Pepys retrieved the clothes and insisted that she be severely whipped. Others were dismissed for drinking or pilfering food. Some almost certainly went because they spurned his amorous fumblings. An amazing number, however, submitted. Pepys’s diary reveals that he had intercourse with at least ten women other than his wife and sexual encounters with forty more. Many were servants. Of one maid, Mary Mercer, the Dictionary of National Biography serenely notes: “Samuel seems to have made a habit of fondling Mercer’s breasts while she dressed him in the morning.” (It is interesting that it is “Samuel” for our rakish hero and “Mercer” for the drudge.) When they weren’t dressing him, absorbing his blows, or providing roosts for his gropes, Pepys’s servants were expected to comb his hair and wash his ears. This was on top of a normal day’s cooking, cleaning, fetching, carrying, and all the rest. Not altogether surprisingly, the Pepyses had great difficulty finding and keeping servants.

Pepys’s experience also demonstrated that servants could betray. In 1679, Pepys dismissed his butler for sleeping with the housekeeper (who, interestingly, remained in his employ). The butler sought revenge by claiming to Pepys’s political enemies that Pepys was a papist. As this happened during a period of religious hysteria, Pepys was imprisoned in the Tower of London. It was only because the butler was seized by conscience and admitted that he had made the whole thing up that Pepys was allowed to go free, but it was a painfully vivid reminder that masters could be as much at the mercy of servants as servants were of masters.

As for the servants themselves, we generally don’t know much about them because their existences went mostly unrecorded. One interesting exception was Hannah Cullwick, who kept an unusually thorough diary for nearly forty years. Cullwick was born in 1833 in Shropshire and entered household service full-time as a pot girl—a kitchen skivvy—at the age of eight. In the course of a long career she was an undermaid, kitchen maid, cook, scullion, and general housekeeper. In all capacities, the work was hard and the hours long. She began her diary in 1859 at the age of twenty-five and kept it up until just shy of her sixty-fifth birthday. Thanks to its span, it constitutes the most complete record of the daily life of an underservant during the great age of servitude. Like most house servants, Cullwick worked from before seven in the morning till nine or ten at night, sometimes later. The diaries are an endless, largely emotionless catalog of tasks performed. Here is a typical entry, for July 14, 1860:

Opened the shutters & lighted the kitchen fire. Shook my sooty thing in the dusthole & emptied the soot there. Swept & dusted the rooms & the hall. Laid the hearth & got breakfast up. Clean’d 2 pairs of boots. Made the beds & emptied the slops. Clean’d & washed the breakfast things up. Clean’d the plate; clean’d the knives & got dinner up. Clean’d away. Clean’d the kitchen up; unpack’d a hamper. Took two chickens to Mrs Brewer’s & brought the message back. Made a tart & pick’d & gutted two ducks & roasted them. Clean’d the steps & flags on my knees. Blackleaded the scraper in front of the house; clean’d the street flags too on my knees. Wash’d up in the scullery. Clean’d the pantry on my knees & scour’d the tables. Scrubbed the flags around the house & clean’d the window sills. Got tea for the Master & Mrs Warwick.… Clean’d the privy & passage & scullery floor on my knees. Wash’d the dog & clean’d the sinks down. Put the supper ready for Ann to take up, for I was too dirty & tired to go upstairs. Wash’d in a bath & to bed.

This is a numbingly typical day. All that is unusual here is that she managed a bath. On most days she concludes her entries with a weary, fatalistic: “Slept in my dirt.”

Beyond her spare account of duties, there was something even more extraordinary about Hannah Cullwick’s life, for she spent thirty-six years of it, from 1873 to her death in 1909, secretly married to her employer, a civil servant and minor poet named Arthur Munby, who never disclosed the relationship to family or friends. When alone, they lived as man and wife; when a visitor called, however, Cullwick stepped back into the role of maid. If overnight guests were present, Cullwick withdrew from the marital bed and slept in the kitchen. Munby was a man of some standing. He numbered among his friends Ruskin, Rossetti, and Browning, and they were frequent visitors to his home, but none had any idea that the woman who called him “Sir” was actually his wife. Even in private, their relationship was a touch unorthodox, to say the least. At his bidding, she called him “massa” and blacked her skin to make herself look like a slave. The diaries, it transpires, were kept largely so that he could read about her getting dirty.

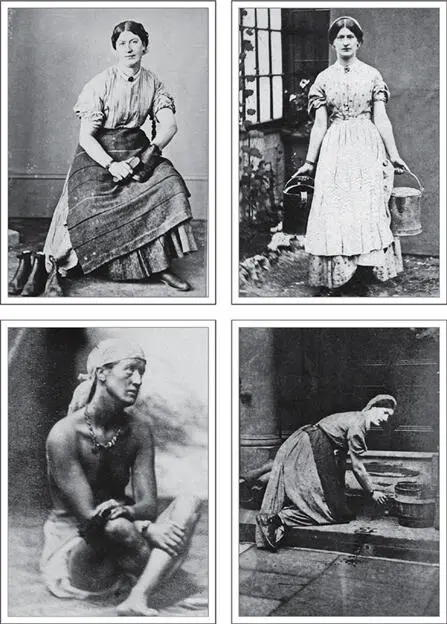

Hannah Cullwick photographed by her husband at various servants’ tasks, and dressed as a chimney sweep (bottom left). Note the locked chain around her neck . (photo credit 5.1)

It was only in 1910, after Munby died and his will was made public, that the news came out, causing a minor sensation. It was her odd marriage rather than her poignant diaries that made Hannah Cullwick famous.

At the bottom of the servant heap were laundrymaids, who were so lowly that often they were kept almost entirely out of sight: others took washing to them so that they would not be seen collecting it. Laundry duty was so despised that in larger households servants were sometimes sent to the laundry as a punishment. It was an exhausting job. In a good-sized country house laundry staff could easily deal with six or seven hundred separate items of clothing, towels, and bed linens every week. Because there were no detergents before the 1850s, most laundry loads had to be soaked in soapy water or lye for hours, then pounded and scrubbed with vigor, boiled for an hour or more, rinsed repeatedly, wrung out by hand or (after about 1850) fed through a roller, and carried outside to be draped over a hedge or spread on a lawn to dry. (One of the commonest of crimes in the countryside was the theft of drying clothes, so someone often had to stay with the laundry until it was dry.) Altogether, according to Judith Flanders in The Victorian House , a straightforward load—one involving sheets and other household linens, say—was likely to incorporate at least eight separate processes. But many loads were far from straightforward. Difficult or delicate fabrics had to be treated with the greatest care, and items of clothing made of different types of fabric—of velvet and lace, say—often had to be carefully taken apart, washed separately, and then sewn back together.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «At Home»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «At Home» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «At Home» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.