Even when confronted by loss and sadness, Frankl’s optimism, his constant affrmation of and exuberance about life, led him to insist that hope and positive energy can turn challenges into triumphs. In Man’s Search for Meaning , he hastens to add that suffering is not necessary to find meaning, only that “meaning is possible in spite of suffering.” Indeed, he goes on to say that “to suffer unnecessarily is masochistic rather than heroic.”

I first read Man’s Search for Meaning as a philosophy professor in the mid-1960s. The book was brought to my attention by a Norwegian philosopher who had himself been incarcerated in a Nazi concentration camp. My colleague remarked how strongly he agreed with Frankl about the importance of nourishing one’s inner freedom, embracing the value of beauty in nature, art, poetry, and literature, and feeling love for family and friends. But other personal choices, activities, relationships, hobbies, and even simple pleasures can also give meaning to life. Why, then, do some people find themselves feeling so empty? Frankl’s wisdom here is worth emphasizing: it is a question of the attitude one takes toward life’s challenges and opportunities, both large and small. A positive attitude enables a person to endure suffering and disappointment as well as enhance enjoyment and satisfaction. A negative attitude intensifies pain and deepens disappointments; it undermines and diminishes pleasure, happiness, and satisfaction; it may even lead to depression or physical illness.

My friend and former colleague Norman Cousins was a tireless advocate for the value of positive emotions in promoting health, and he warned of the danger that negative emotions may jeopardize it. Although some critics attacked Cousins’s views as simplistic, subsequent research in psychoneuroimmunology has supported the ways in which positive emotions, expectations, and attitudes enhance our immune system. This research also reinforces Frankl’s belief that one’s approach to everything from life-threatening challenges to everyday situations helps to shape the meaning of our lives. The simple truth that Frankl so ardently promoted has profound significance for anyone who listens.

The choices humans make should be active rather than passive. In making personal choices we affrm our autonomy. “A human being is not one thing among others; things determine each other,” Frankl writes, “but man is ultimately self determining. What he becomes—within the limits of endowment and environment—he has made out of himself.” For example, the darkness of despair threatened to overwhelm a young Israeli soldier who had lost both his legs in the Yom Kippur War. He was drowning in depression and contemplating suicide. One day a friend noticed that his outlook had changed to hopeful serenity. The soldier attributed his transformation to reading Man’s Search for Meaning . When he was told about the soldier, Frankl wondered whether “there may be such a thing as autobibliotherapy—healing through reading.”

Frankl’s comment hints at the reasons why Man’s Search for Meaning has such a powerful impact on many readers. Persons facing existential challenges or crises may seek advice or guidance from family, friends, therapists, or religious counselors. Sometimes such advice is helpful; sometimes it is not. Persons facing diffcult choices may not fully appreciate how much their own attitude interferes with the decision they need to make or the action they need to take. Frankl offers readers who are searching for answers to life’s dilemmas a critical mandate: he does not tell people what to do, but why they must do it.

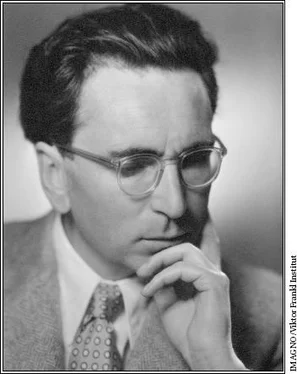

After his liberation in 1945 from the Türkheim camp, where he had nearly died of typhus, Frankl discovered that he was utterly alone. On the first day of his return to Vienna in August 1945, Frankl learned that his pregnant wife, Tilly, had died of sickness or starvation in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Sadly, his parents and brother had all died in the camps. Overcoming his losses and inevitable depression, he remained in Vienna to resume his career as a psychiatrist—an unusual choice when so many others, especially Jewish psychoanalysts and psychiatrists, had emigrated to other countries. Several factors may have contributed to this decision: Frankl felt an intense connection to Vienna, especially to psychiatric patients who needed his help in the postwar period. He also believed strongly in reconciliation rather than revenge; he once remarked, “I do not forget any good deed done to me, and I do not carry a grudge for a bad one.” Notably, he renounced the idea of collective guilt. Frankl was able to accept that his Viennese colleagues and neighbors may have known about or even participated in his persecution, and he did not condemn them for failing to join the resistance or die heroic deaths. Instead, he was deeply committed to the idea that even a vile Nazi criminal or a seemingly hopeless madman has the potential to transcend evil or insanity by making responsible choices.

He threw himself passionately into his work. In 1946 he reconstructed and revised the book that was destroyed when he was first deported (The Doctor and the Soul), and that same year—in only nine days—he wrote Man’s Search for Meaning . He hoped to cure through his writings the personal alienation and cultural malaise that plagued many individuals who felt an “inner emptiness” or a “void within themselves.” Perhaps this flurry of professional activity helped Frankl to restore meaning to his own life.

Two years later he married Eleanore Schwindt, who, like his first wife, was a nurse. Unlike Tilly, who was Jewish, Elly was Catholic. Although this may have been mere coincidence, it was characteristic of Viktor Frankl to accept individuals regardless of their religious beliefs or secular convictions. His deep commitment to the uniqueness and dignity of each individual was illustrated by his admiration for Freud and Adler even though he disagreed with their philosophical and psychological theories. He also valued his personal relationships with philosophers as radically different as Martin Heidegger, a reformed Nazi sympathizer, Karl Jaspers, an advocate of collective guilt, and Gabriel Marcel, a Catholic philosopher and writer. As a psychiatrist, Frankl avoided direct reference to his personal religious beliefs. He was fond of saying that the aim of psychiatry was the healing of the soul, leaving to religion the salvation of the soul.

He remained head of the neurology department at the Vienna Policlinic Hospital for twenty-five years and wrote more than thirty books for both professionals and general readers. He lectured widely in Europe, the Americas, Australia, Asia, and Africa; held professorships at Harvard, Stanford, and the University of Pittsburgh; and was Distinguished Professor of Logotherapy at the U.S. International University in San Diego. He met with politicians, world leaders such as Pope Paul VI, philosophers, students, teachers, and numerous individuals who had read and been inspired by his books. Even in his nineties, Frankl continued to engage in dialogue with visitors from all over the world and to respond personally to some of the hundreds of letters he received every week. Twenty-nine universities awarded him honorary degrees, and the American Psychiatric Association honored him with the Oskar Pfister Award.

Frankl is credited with establishing logotherapy as a psychiatric technique that uses existential analysis to help patients resolve their emotional conflicts. He stimulated many therapists to look beyond patients’ past or present problems to help them choose productive futures by making personal choices and taking responsibility for them. Several generations of therapists were inspired by his humanistic insights, which gained influence as a result of Frankl’s prolific writing, provocative lectures, and engaging personality. He encouraged others to use existential analysis creatively rather than to establish an offcial doctrine. He argued that therapists should focus on the specific needs of individual patients rather than extrapolate from abstract theories.

Читать дальше