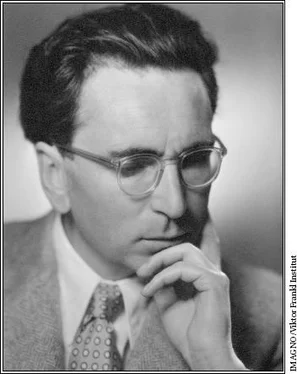

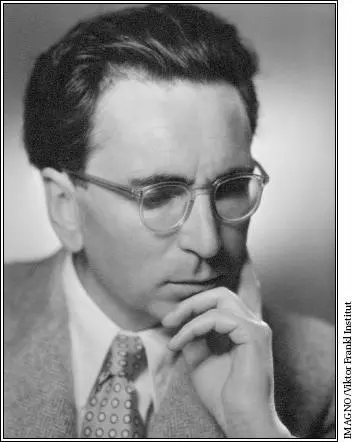

Viktor E. Frankl, c. 1949

To the

memory of

my mother

CONTENTS

FOREWORD • HAROLD S. KUSHNER

PREFACE TO THE 1992 EDITION

I

EXPERIENCES IN A CONCENTRATION CAMP

II

LOGOTHERAPY IN A NUTSHELL

POSTSCRIPT 1984

THE CASE FOR A TRAGIC OPTIMISM

AFTERWORD • WILLIAM J. WINSLADE

FOREWORD

VIKTOR FRANKL’S Man’s Search for Meaning is one of the great books of our time. Typically, if a book has one passage, one idea with the power to change a person’s life, that alone justifies reading it, rereading it, and finding room for it on one’s shelves. This book has several such passages.

It is first of all a book about survival. Like so many German and East European Jews who thought themselves secure in the 1930s, Frankl was cast into the Nazi network of concentration and extermination camps. Miraculously, he survived, in the biblical phrase “a brand plucked from the fire.” But his account in this book is less about his travails, what he suffered and lost, than it is about the sources of his strength to survive. Several times in the course of the book, Frankl approvingly quotes the words of Nietzsche: “He who has a Why to live for can bear almost any How.” He describes poignantly those prisoners who gave up on life, who had lost all hope for a future and were inevitably the first to die. They died less from lack of food or medicine than from lack of hope, lack of something to live for. By contrast, Frankl kept himself alive and kept hope alive by summoning up thoughts of his wife and the prospect of seeing her again, and by dreaming at one point of lecturing after the war about the psychological lessons to be learned from the Auschwitz experience. Clearly, many prisoners who desperately wanted to live did die, some from disease, some in the crematoria. But Frankl’s concern is less with the question of why most died than it is with the question of why anyone at all survived.

Terrible as it was, his experience in Auschwitz reinforced what was already one of his key ideas: Life is not primarily a quest for pleasure, as Freud believed, or a quest for power, as Alfred Adler taught, but a quest for meaning. The greatest task for any person is to find meaning in his or her life. Frankl saw three possible sources for meaning: in work (doing something significant), in love (caring for another person), and in courage during diffcult times. Suffering in and of itself is meaningless; we give our suffering meaning by the way in which we respond to it. At one point, Frankl writes that a person “may remain brave, dignified and unselfish, or in the bitter fight for self-preservation he may forget his human dignity and become no more than an animal.” He concedes that only a few prisoners of the Nazis were able to do the former, “but even one such example is suffcient proof that man’s inner strength may raise him above his outward fate.”

Finally, Frankl’s most enduring insight, one that I have called on often in my own life and in countless counseling situations: Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you.

There is a scene in Arthur Miller’s play Incident at Vichy in which an upper-middle-class professional man appears before the Nazi authority that has occupied his town and shows his credentials: his university degrees, his letters of reference from prominent citizens, and so on. The Nazi asks him, “Is that everything you have?” The man nods. The Nazi throws it all in the wastebasket and tells him: “Good, now you have nothing.” The man, whose self-esteem had always depended on the respect of others, is emotionally destroyed. Frankl would have argued that we are never left with nothing as long as we retain the freedom to choose how we will respond.

My own congregational experience has shown me the truth of Frankl’s insights. I have known successful businessmen who, upon retirement, lost all zest for life. Their work had given their lives meaning. Often it was the only thing that had given their lives meaning and, without it, they spent day after day sitting at home, depressed, “with nothing to do.” I have known people who rose to the challenge of enduring the most terrible afflictions and situations as long as they believed there was a point to their suffering. Whether it was a family milestone they wanted to live long enough to share or the prospect of doctors finding a cure by studying their illness, having a Why to live for enabled them to bear the How.

And my own experience echoes Frankl’s in another way. Just as the ideas in my book When Bad Things Happen to Good People gained power and credibility because they were offered in the context of my struggle to understand the illness and death of our son, Frankl’s doctrine of logotherapy, curing the soul by leading it to find meaning in life, gains credibility against the background of his anguish in Auschwitz. The last half of the book without the first would be far less effective.

I find it significant that the Foreword to the 1962 edition of Man’s Search for Meaning was written by a prominent psychologist, Dr. Gordon Allport, and the Foreword to this new edition is written by a clergyman. We have come to recognize that this is a profoundly religious book. It insists that life is meaningful and that we must learn to see life as meaningful despite our circumstances. It emphasizes that there is an ultimate purpose to life. And in its original version, before a postscript was added, it concluded with one of the most religious sentences written in the twentieth century:

We have come to know Man as he really is. After all, man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the

Shema Yisrael

on his lips.

H

AROLD

S. K

USHNER

Harold S. Kushner is rabbi emeritus at Temple Israel in Natick, Massachusetts, and the author of several best-selling books, including When Bad Things Happen to Good People, Living a Life That Matters, and When All You’ve Ever Wanted Isn’t Enough.

PREFACE TO

THE 1992 EDITION

THIS BOOK HAS NOW LIVED TO SEE nearly one hundred printings in English—in addition to having been published in twenty-one other languages. And the English editions alone have sold more than three million copies.

These are the dry facts, and they may well be the reason why reporters of American newspapers and particularly of American TV stations more often than not start their interviews, after listing these facts, by exclaiming: “Dr. Frankl, your book has become a true bestseller—how do you feel about such a success?” Whereupon I react by reporting that in the first place I do not at all see in the bestseller status of my book an achievement and accomplishment on my part but rather an expression of the misery of our time: if hundreds of thousands of people reach out for a book whose very title promises to deal with the question of a meaning to life, it must be a question that burns under their fingernails.

To be sure, something else may have contributed to the impact of the book: its second, theoretical part (“Logother- apy in a Nutshell”) boils down, as it were, to the lesson one may distill from the first part, the autobiographical account (“Experiences in a Concentration Camp”), whereas Part One serves as the existential validation of my theories. Thus, both parts mutually support their credibility.

Читать дальше