Our generation is realistic, for we have come to know man as he really is. After all, man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips.

This part, which has been revised and updated, first appeared as “Basic Concepts of Logotherapy” in the 1962 edition of Man’s Search for Meaning .

1. It was the first version of my first book, the English translation of which was published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York, in 1955, under the title The Doctor and the Soul: An Introduction to Logotherapy .

2. Magda B. Arnold and John A. Gasson, The Human Person , Ronald Press, New York, 1954, p. 618.

3. A phenomenon that occurs as the result of a primary phenomenon.

4. “Some Comments on a Viennese School of Psychiatry,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 51 (1955), pp. 701–3.

5. “Logotherapy and Existential Analysis,” Acta Psychotherapeutica , 6 (1958), pp. 193–204.

6. A prayer for the dead.

7. L’kiddush basbem , i.e., for the sanctification of God’s name.

8. “Thou hast kept count of my tossings; put thou my tears in thy bottle! Are they not in thy book?” (Ps. 56, 8.)

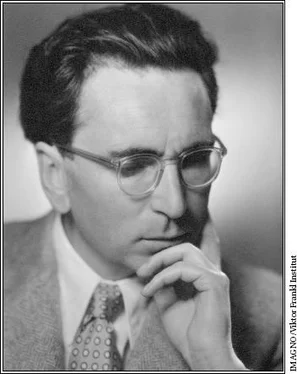

9. In order to treat cases of sexual impotence, a specific logotherapeutic technique has been developed, based on the theory of hyper-intention and hyper-reflection as sketched above (Viktor E. Frankl, “The Pleasure Principle and Sexual Neurosis,” The International Journal of Sexology , Vol. 5, No. 3 [1952], pp. 128–30). Of course, this cannot be dealt with in this brief presentation of the principles of logotherapy.

10. Viktor E. Frankl, “Zur medikamentösen Unterstützung der Psychotherapie bei Neurosen,” Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie , Vol. 43, pp. 26–31.

11. New York, The Macmillan Co., 1956, p. 92.

12. The fear of sleeplessness is, in the majority of cases, due to the patient’s ignorance of the fact that the organism provides itself by itself with the minimum amount of sleep really needed.

13. American Journal of Psychotherapy , 10 (1956), p. 134.

14. “Some Comments on a Viennese School of Psychiatry,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 51 (1955), pp. 701–3.

15. This is often motivated by the patient’s fear that his obsessions indicate an imminent or even actual psychosis; the patient is not aware of the empirical fact that an obsessive-compulsive neurosis is immunizing him against a formal psychosis rather than endangering him in this direction.

16. This conviction is supported by Allport who once said, “As the focus of striving shifts from the conflict to selfless goals, the life as a whole becomes sounder even though the neurosis may never completely disappear” (op. cit., p. 95).

17. “Value Dimensions in Teaching,” a color television film produced by Hollywood Animators, Inc., for the California Junior College Association.

POSTSCRIPT

1984

Dedicated to the memory of

Edith Weisskopf-Joelson, whose

pioneering efforts in logotherapy

in the United States began as early

as 1955 and whose contributions

to the field have been invaluable.

THE CASE FOR A

TRAGIC OPTIMISM

LET US FIRST ASK OURSELVES WHAT SHOULD BE understood by “a tragic optimism.” In brief it means that one is, and remains, optimistic in spite of the “tragic triad,” as it is called in logotherapy, a triad which consists of those aspects of human existence which may be circumscribed by: (1) pain; (2) guilt; and (3) death. This chapter, in fact, raises the question, How is it possible to say yes to life in spite of all that? How, to pose the question differently, can life retain its potential meaning in spite of its tragic aspects? After all, “saying yes to life in spite of everything,” to use the phrase in which the title of a German book of mine is couched, presupposes that life is potentially meaningful under any conditions, even those which are most miserable. And this in turn presupposes the human capacity to creatively turn life’s negative aspects into something positive or constructive. In other words, what matters is to make the best of any given situation. “The best,” however, is that which in Latin is called optimum —hence the reason I speak of a tragic optimism, that is, an optimism in the face of tragedy and in view of the human potential which at its best always allows for: (1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life’s transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action.

This chapter is based on a lecture I presented at the Third World Congress of Logotherapy, Regensburg University, West Germany, June 1983.

It must be kept in mind, however, that optimism is not anything to be commanded or ordered. One cannot even force oneself to be optimistic indiscriminately, against all odds, against all hope. And what is true for hope is also true for the other two components of the triad inasmuch as faith and love cannot be commanded or ordered either.

To the European, it is a characteristic of the American culture that, again and again, one is commanded and ordered to “be happy.” But happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue. One must have a reason to “be happy.” Once the reason is found, however, one becomes happy automatically. As we see, a human being is not one in pursuit of happiness but rather in search of a reason to become happy, last but not least, through actualizing the potential meaning inherent and dormant in a given situation.

This need for a reason is similar in another specifically human phenomenon—laughter. If you want anyone to laugh you have to provide him with a reason, e.g., you have to tell him a joke. In no way is it possible to evoke real laughter by urging him, or having him urge himself, to laugh. Doing so would be the same as urging people posed in front of a camera to say “cheese,” only to find that in the finished photographs their faces are frozen in artificial smiles.

In logotherapy, such a behavior pattern is called “hyper-intention.” It plays an important role in the causation of sexual neurosis, be it frigidity or impotence. The more a patient, instead of forgetting himself through giving himself, directly strives for orgasm, i.e., sexual pleasure, the more this pur- suit of sexual pleasure becomes self-defeating. Indeed, what is called “the pleasure principle” is, rather, a fun-spoiler.

Once an individual’s search for a meaning is successful, it not only renders him happy but also gives him the capabil- ity to cope with suffering. And what happens if one’s groping for a meaning has been in vain? This may well result in a fa- tal condition. Let us recall, for instance, what sometimes happened in extreme situations such as prisoner-of-war camps or concentration camps. In the first, as I was told by Amer- ican soldiers, a behavior pattern crystallized to which they referred as “give-up-itis.” In the concentration camps, this behavior was paralleled by those who one morning, at five, refused to get up and go to work and instead stayed in the hut, on the straw wet with urine and feces. Nothing—neither warnings nor threats—could induce them to change their minds. And then something typical occurred: they took out a cigarette from deep down in a pocket where they had hidden it and started smoking. At that moment we knew that for the next forty-eight hours or so we would watch them dying. Meaning orientation had subsided, and consequently the seeking of immediate pleasure had taken over.

Читать дальше