5. “Basic Theoretical Concepts of Humanistic Psychology,” American Psychologist , XXVI (April 1971), p. 378.

6. “The Place of Logotherapy in the World Today,” The International Forum for Logotherapy , Vol. 1, No. 3 (1980), pp. 3–7.

7. W. H. Sledge, J. A. Boydstun and A. J. Rabe, “Self-Concept Changes Related to War Captivity,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry , 37 (1980), pp. 430–443.

8. “The Defiant Power of the Human Spirit” was in fact the title of a paper presented by Long at the Third World Congress of Logotherapy in June 1983.

9. I won’t forget an interview I once heard on Austrian TV, given by a Polish cardiologist who, during World War II, had helped organize the War- saw ghetto upheaval. “What a heroic deed,” exclaimed the reporter. “Listen,” calmly replied the doctor, “to take a gun and shoot is no great thing; but if the SS leads you to a gas chamber or to a mass grave to execute you on the spot, and you can’t do anything about it—except for going your way with dignity—you see, this is what I would call heroism.” Attitudinal heroism, so to speak.

10. See also Joseph B. Fabry, The Pursuit of Meaning , New York, Harper and Row, 1980.

11. Cf. Viktor E. Frankl, The Unheard Cry for Meaning , New York, Simon and Schuster, 1978, pp. 42–43.

12. See also Viktor E. Frankl, Psychotherapy and Existentialism , New York, Simon and Schuster, 1967.

13. “Transference and Countertransference in Logotherapy,” The International Forum for Logotherapy , Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 1982), pp. 115–18.

14. Logotherapy is not imposed on those who are interested in psychotherapy. It is not comparable to an Oriental bazaar but rather to a supermarket. In the former, the customer is talked into buying something. In the latter, he is shown, and offered, various things from which he may pick what he deems usable and valuable.

AFTERWORD

ON JANUARY 27, 2006, the sixty-first anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp, where 1.5 million people died, nations around the world observed the first International Holocaust Remembrance Day. A few months later, they might well have celebrated the anniversary of one of the most abiding pieces of writing from that horrendous time. First published in German in 1946 as A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp and later called Say Yes to Life in Spite of Everything, subsequent editions were supplemented by an introduction to logotherapy and a postscript on tragic optimism, or how to remain optimistic in the face of pain, guilt, and death. The English translation, first published in 1959, was called Man’s Search for Meaning .

Viktor Frankl’s book has now sold more than 12 million copies in a total of twenty-four languages. A 1991 Library of Congress/Book-of-the-Month-Club survey asking readers to name a “book that made a difference in your life” found Man’s Search for Meaning among the ten most influential books in America. It has inspired religious and philosophical thinkers, mental-health professionals, teachers, students, and general readers from all walks of life. It is routinely assigned to college, graduate, and high school students in psychology, philosophy, history, literature, Holocaust studies, religion, and theology. What accounts for its pervasive influence and enduring value?

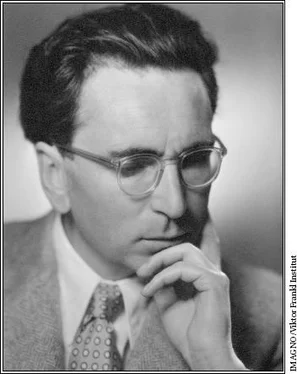

Viktor Frankl’s life spanned nearly all of the twentieth century, from his birth in 1905 to his death in 1997. At the age of three he decided to become a physician. In his autobiographical reflections, he recalls that as a youth he would “think for some minutes about the meaning of life. Particularly about the meaning of the coming day and its meaning for me .”

As a teenager Frankl was fascinated by philosophy, experimental psychology, and psychoanalysis. To supplement his high school classes, he attended adult-education classes and began a correspondence with Sigmund Freud that led Freud to submit a manuscript of Frankl’s to the International Journal of Psychoanalysis . The article was accepted and later published. That same year, at age sixteen, Frankl attended an adult-education workshop on philosophy. The instructor, recognizing Frankl’s precocious intellect, invited him to give a lecture on the meaning of life. Frankl told the audience that “It is we ourselves who must answer the questions that life asks of us, and to these questions we can respond only by being responsible for our existence.” This belief became the cornerstone of Frankl’s personal life and professional identity.

Under the influence of Freud’s ideas, Frankl decided while he was still in high school to become a psychiatrist. Inspired in part by a fellow student who told him he had a gift for helping others, Frankl had begun to realize that he had a talent not only for diagnosing psychological problems, but also for discovering what motivates people.

Frankl’s first counseling job was entirely his own—he founded Vienna’s first private youth counseling program and worked with troubled youths. From 1930 to 1937 he worked as a psychiatrist at the University Clinic in Vienna, caring for suicidal patients. He sought to help his patients find a way to make their lives meaningful even in the face of depression or mental illness. By 1939 he was head of the department of neurology at Rothschild Hospital, the only Jewish hospital in Vienna.

In the early years of the war, Frankl’s work at Rothschild gave him and his family some degree of protection from the threat of deportation. When the hospital was closed down by the National Socialist government, however, Frankl realized that they were at grave risk of being sent to a concentration camp. In 1942 the American consulate in Vienna informed him that he was eligible for a U.S. immigration visa. Although an escape from Austria would have enabled him to complete his book on logotherapy, he decided to let his visa lapse: he felt he should stay in Vienna for the sake of his aging parents. In September 1942, Frankl and his family were arrested and deported. Frankl spent the next three years at four different concentration camps—Theresienstadt, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Kaufering, and Türkheim, part of the Dachau complex.

It is important to note that Frankl’s imprisonment was not the only impetus for Man’s Search for Meaning . Before his deportation, he had already begun to formulate an argument that the quest for meaning is the key to mental health and human flourishing. As a prisoner, he was suddenly forced to assess whether his own life still had any meaning. His sur- vival was a combined result of his will to live, his instinct for self-preservation, some generous acts of human decency, and shrewdness; of course, it also depended on blind luck, such as where he happened to be imprisoned, the whims of the guards, and arbitrary decisions about where to line up and who to trust or believe. However, something more was needed to overcome the deprivations and degradations of the camps. Frankl drew constantly upon uniquely human capacities such as inborn optimism, humor, psychological detachment, brief moments of solitude, inner freedom, and a steely resolve not to give up or commit suicide. He realized that he must try to live for the future, and he drew strength from loving thoughts of his wife and his deep desire to finish his book on logotherapy. He also found meaning in glimpses of beauty in nature and art. Most important, he realized that, no matter what happened, he retained the freedom to choose how to respond to his suffering. He saw this not merely as an option but as his and every person’s responsibility to choose “the way in which he bears his burden.”

Sometimes Frankl’s ideas are inspirational, as when he explains how dying patients and quadriplegics come to terms with their fate. Others are aspirational, as when he asserts that a person finds meaning by “striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a freely chosen task.” He shows how existential frustration provoked and motivated an unhappy diplomat to seek a new, more satisfying career. Frankl also uses moral exhortation, however, to call attention to “the gap between what one is and what one should become” and the idea that “man is responsible and must actualize the potential meaning of his life.” He sees freedom and responsibility as two sides of the same coin. When he spoke to American audiences, Frankl was fond of saying, “I recommend that the Statue of Liberty on the East Coast be supplemented by a Statue of Responsibility on the West Coast.” To achieve personal meaning, he says, one must transcend subjective pleasures by doing something that “points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself … by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love.” Frankl himself chose to focus on his parents by staying in Vienna when he could have had safe passage to America. While he was in the same concentration camp as his father, Frankl managed to obtain morphine to ease his father’s pain and stayed by his side during his dying days.

Читать дальше