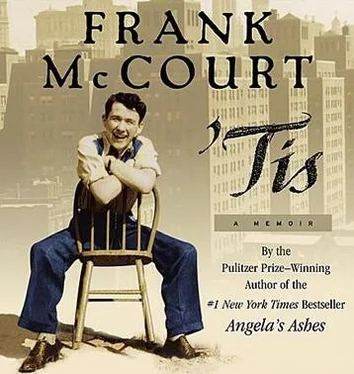

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They meet me on the streets and tell me I look grand, that I look more like a Yank all the time. Alice Egan argues, Frankie McCourt hasn’t changed one hour, not one hour. Isn’t that right, Frankie?

I don’t know, Alice.

You don’t have the slightest bit of an American accent.

Whatever friends I had in Limerick are gone, dead or emigrated, and I don’t know what to do with myself. I could read all day in my mother’s house but why did I come all the way from New York to sit on my arse and read? I could sit in pubs all night and drink but I could have done that in New York, too.

I walk from one end of the city to the other and out into the country where my father walked endlessly. People are polite but they’re working and they have families and I’m a visitor, a returned Yank.

Is that yourself, Frankie McCourt?

’Tis.

When did you come?

Last week.

And when are you going back?

Next week.

That’s grand. I’m sure your poor mother is glad to have you at home and I hope the weather keeps fine for you.

They say, I suppose you notice all kinds of changes in Limerick?

Oh, yes. More cars, fewer snotty noses and scabby knees. No barefoot children. No women in shawls.

Jesus, Frankie McCourt, them’s peculiar things to be noticing.

They’ll watch to see if I put on airs and they’ll cut me down but I have none to put on. When I tell them I’m a teacher they seem disappointed.

Only a teacher. Lord above, Frankie McCourt, we thought you’d be a millionaire by now. Sure wasn’t your brother Malachy here with his glamorous model of a wife and isn’t he an actor and everything.

The plane lifts into a western sun which touches the Shannon with gold and even though I’m happy to be returning to New York I hardly know where I belong anymore.

43

Malachy’s bar is so successful he provides passage for my mother and my brother Alphie, on the SS Sylvania which arrives in New York on December 21, 1959.

When they emerge from the customs shed there’s a piece of broken leather flapping from Mam’s right shoe so that you can see the small toe of a foot that was always swollen. Does it ever end? Is this the family of the broken shoe? We embrace and Alphie smiles with broken blackened teeth.

The family of broken shoes and teeth destroyed. Will this be our coat of arms?

Mam looks past me to the street beyond. Where’s Malachy?

I don’t know. He should be here in a minute.

She tells me I look fine, that it didn’t do me any harm to put on a bit of weight though I should do something about my eyes they’re that red. That irritates me because I know that if I even think of my eyes or anyone mentions them I can feel them flush red and of course she notices.

See, she says. You’re a bit old to be having bad eyes.

I want to snap at her that I’m twenty-nine and I don’t know the proper age for not having bad eyes and is this what she wants to talk about the minute she arrives in New York? but Malachy arrives in a taxi with his wife, Linda. More smiles and embraces. Malachy keeps the taxi while we retrieve the suitcases.

Alphie says, Will we put these in the boot?

Linda smiles. Oh, no, we put them in the trunk.

Trunk? We didn’t bring a trunk.

No, no, she says, we put your bags in the trunk of the taxi.

Isn’t there a boot in the taxi?

No, that’s the trunk.

Alphie scratches his head and smiles again, a young man understanding lesson number one in American English.

In the taxi Mam says, Lord above, look at all those motor cars. The roads are packed. I tell her it’s not so bad now. An hour earlier it was the height of the rush hour and traffic was even worse. She says she doesn’t see how it could ever be worse. I tell her it’s always worse earlier and she says, I don’t see how it could be worse than this the way the motor cars are crawling along this minute.

I am trying to be patient and I speak slowly. I am telling you, Mam, this is how the traffic is in New York. I live here.

Malachy says, Oh, it doesn’t matter. It’s a lovely morning, and she says, I lived here, too, in case you’ve forgotten.

You did, I tell her. Twenty-five years ago and you lived in Brooklyn, not Manhattan.

Well, it’s still New York.

She won’t give up and I won’t though I’m looking at the pettiness of the two of us and wondering why I’m arguing instead of celebrating the arrival of my mother and my youngest brother in the city all of us dreamed of all our lives. Why does she pick on my eyes and why do I have to contradict her over the traffic?

Linda tries to ease the moment. Well, as Malachy says, it is a beautiful day.

Mam gives a little begrudging nod. ’Tis.

And how was the weather when you left Ireland, Mam?

A begrudging word, Raining.

Oh, it’s always raining in Ireland, isn’t it, Mam?

No, it’s not, and she folds her arms and stares straight ahead at the traffic that was much busier an hour earlier.

At the apartment Linda makes breakfast while Mam dandles the new baby, Siobhan, and croons to her the way she crooned to seven of us. Linda says, Mam, would you like tea or coffee?

Tea, please.

When the breakfast is ready Mam puts the baby down, comes to the table and wants to know what is that thing floating around in her cup. Linda tells her it’s a tea bag and Mam puts her nose in the air. Oh, I wouldn’t drink that. Sure, that’s not proper tea at all.

Malachy’s face tightens and he tells her through his teeth, That’s the tea we have. That’s the way we make it. We don’t have a pound of Lyons’ tea and a teapot for you.

Well, then, I won’t have anything. I’ll just eat my egg. I don’t know what kind of country this is where you can’t get a decent cup of tea.

Malachy is ready to say something but the baby cries and he goes to lift her from her crib while Linda flutters around Mam, smiling, trying to please. We could get a teapot, Mam, and we could get loose tea, couldn’t we, Malachy?

But he’s parading the living room with the baby whimpering on his shoulder and you can see that in the matter of tea bags he won’t yield, not this morning anyway. Like anyone who has ever had a decent cup of tea in Ireland he despises tea bags but he has an American wife who knows nothing but tea bags, he has a baby and things on his mind and little patience with this mother with her nose in the air over tea bags her first day in the United States of America and he doesn’t know why, after all his expense and trouble, he has to tolerate her picky ways for the next three weeks in this small apartment.

Mam pushes away from the table. Lavatory? she asks Linda. Where’s the lavatory?

What?

Lavatory. WC.

Linda looks at Malachy. The toilet, he says. The bathroom.

Oh, says Linda. In there.

While Mam is in the bathroom Alphie tells Linda the tea bag wasn’t that bad after all. If you didn’t see it floating in the cup you’d think it was all right, and Linda smiles again. She tells him that’s why the Chinese don’t serve great chunks of meat. They don’t like looking at the animal they’re eating. If they cook chicken they chop it into little pieces and mix it with other things so you barely know it’s chicken. That’s why you never see a chicken leg or breast in a Chinese restaurant.

Is that right? Alphie says.

The baby is still whimpering on Malachy’s shoulder but all is sweet at the table with Alphie and Linda discussing tea bags and the delicacy of Chinese cooking. Then Mam comes from the bathroom and tells Malachy, That child is full of wind, so she is. I’ll take her.

Malachy hands over Siobhan and sits at the table with his tea. Mam walks the floor with the piece of leather flapping from her broken shoe and I know I’ll have to take her down Third Avenue to a shoe shop. She pats the baby and there’s a powerful burp that makes us all laugh. She puts the baby back in the crib and leans over her. There, there, leanv, there, there, and the baby gurgles. She returns to the table, rests her hands in her lap and tells us, I’d give me two eyes for a decent cup of tea, and Linda tells her she’ll go out today and get a teapot and loose tea, right, Malachy?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.