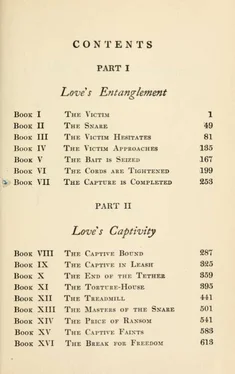

Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"It wouldn't be ugliness," replied he. "It would be Nature ! 'Blessings on thee, little man !'

"That's all very well. But I want Cedric to have curls '

"Curls!" he cried. "And then a Fauntleroy suit, I suppose!"

"No—at least not while we're poor. But I want him to look decent '

"If you have curls, then you'll want a nurse-maid to brush them!"

"Nonsense, Thyrsis! Can't a mother take care of her child's own hair?"

"Some mothers can—they have nothing better to do. But if you were going in for the hair-dresser's art, why did you cut off your own?"

And so would come yet new discussions. "You'll be wanting me to maintain an establishment!" Thyrsis would cry, whenever these aesthetic impulses manifested themselves. He seemed to be haunted by that image of an establishment. All married men came to it in the end —there seemed to be something in matrimony that predisposed to it; and far better adopt at once the ideals and habits of the gypsies, than to settle into respectability with a nurse-maid and a cook!

Thyrsis was under the necessity of sweeping clean his soul, because of all the luxury and wantonness he saw in this metropolis, and the madness to which it goaded his soul. Some day fame would come to him, he knew—wealth also,, perhaps; and oh, there must be one man in all the city who was not corrupted, who did not learn extravagance and self-indulgence, who prac-

ticed as well as preached the life of faith! And so, again and again, he and Corydon would renew the pledges of their courtship-days—pledges to a discipline of Spartan sternness.

Poor as he was, Thyrsis still found time to figure over the things he meant to do when he got money: the publishing-house that was to bring out his books at cost, and the free reading-rooms and the circulating libraries. Also, he wanted to edit a magazine; for there was a great truth which he wished to teach the world. "We must make these things that we have suffered count for something!" he would say to Corydon, again and again. "We must use them to open people's eyes!" He was thinking how, when at last he had escaped from the pit, he would be in a position to speak for those others who were left behind. Men would heed him then, and he could show them how impossible it was for the creative artist to do his work, and at the same time carry on the struggle for bread. He would induce some rich man to set aside a fund for the endowment of young writers; and so the man who had a real message might no longer have to starve.

Thyrsis had by this time tried all the world, and he knew that there was no one to understand. Just about now he was utterly stranded, and had to borrow money for even his next day's food. And oh, the humiliations and insults that came with these loans! And worse yet, the humiliations and insults that came without any loans! There was one rich man who advanced him ten dollars; Thyrsis, when he returned it, sent a check he had received from some out-of-town magazine—and in return was rebuked by the rich man for failing to include the "exchange" on the check. Thyrsis wrote humbly to inquire what manner of thing the "exchange"

on a check might be; and learned that he was still in the rich man's debt to the sum of ten cents!

His case was the more hopeless, he found, because he was a married man. The world might have pardoned a young free-Jance who was willing to "rough it" and take his chances for a while; but a man who had a wife and child—and was still prating about poetry! To the world the possession of a wife and child meant self-indulgence; and when a man had fallen into that trap, he simply had to settle down and take the consequence. How could Thyrsis explain that his marriage had not been as other men's? How could he hint at such a thing, without proving himself a cad?

§ 10. THE work of "contemporary biography" had come to an end; there followed weeks of seeking, and then another opening appeared—Mr. Ardsley offered him a chance to do some manuscript-reading. This was really a splendid opportunity, for the work would not be difficult, and the payment would be five dollars for each manuscript. Thyrsis accepted joyfully, and forthwith carried off a couple of embryo books to his room.

It was a new and curious occupation, which opened up to him whole worlds whose existence he had not previously suspected. Through his review-writing he had become acquainted with the books that had seen the light of day; now he made the startling discovery that for every one that was born, there were hundreds, perhaps thousands, that died in the womb. He could see how it went—the hordes of half-educated people who read books and were moved to write something like them. Each manuscript was a separate tragedy; and often there would be a letter or a preface to make

certain that one did not miss the.sense of it. Here would be a settlement-worker, burning with a message, but unable to draw a character or to write dialogue; here would be a business-man, who had studied up the dialect of the region where he spent his summer vacations, and whose style was so crude that one winced as he turned the pages; here would be a poor bookkeeper, or a typewriter, or other cog in the business machine, who had read of the fortunes made by writers of fiction, and had spent all his hours of leisure for a year in composing a tale of the grand monde, or some feeble imitation of the sugar-coated "historical romance" of the hour.

Sometimes as he read these manuscripts, a shudder would come over Thyrsis; how they made him realize the odds in the game of life! These thousands and tens of thousands panting and striving for success; and he lost in the throng of them! What madness it seemed to imagine that he might climb over their heads -that he had been chosen to scale the heights of fame! Their letters and prefaces sounded like a satire upon his own attitude, a reductio ad absurdum of his claims to "genius". Here, for instance, was a man who wrote to introduce himself as America's first epic poet —stating incidentally that he was an inspector of gas-meters, and had a wife and six children. His poem occupied some six hundred foolscap sheets, finely bound up by hand; it set forth the soul-states of a Byron from Alabama—an aristocratic hero who was refused by the lady of his heart, and voiced his anger and perplexity in a long speech, two lines of which stamped themselves forever upon the mind of the reader

"But I! he cried. My limbs are straight, My purse well-filled, my veins all F. F. V. !"

LOVE'S PILGRIMAGE

As a method of earning one's living, this was almost too good to be true. The worse the manuscripts were, the easier was his task; in fact, when he came upon one which showed traces of real power and interest he cursed his fate, for then it might take several days to earn his five dollars. But for the most part the manuscripts were bad enough, and he could have earned a year's income in a week, if only there had been enough of them. So he made a great effort to succeed at the work, and filled his reports with epigrams and keen observations, carefully adapted to what he knew was Mr. Ardsley's point of view. He allowed time for these devices to be effective, and then paid a visit to find out about the prospects.

"Mr. Ardsley," he began, "I am going to try to meet you half way with a book."

"Ah!" said the other.

"I want to write a novel that you can publish. I believe that I can do it."

Mr. Ardsley warmed immediately. "I have always been certain that you could," said he. He went on to expound to Thyrsis the ethics of opportunism—how it would not be necessary to be false to his convictions, to write anything that he did not believe—but simply to put his convictions into a popular form, and to impart no more than the public could swallow at the first mouthful.

Thyrsis told him the outline of a plot. He would write a story of the struggles of a young author in the metropolis—not such a young author as himself, a rebel and a frenzied egotist, but a plain, everyday young author whom other people could care about. He had the "local color" for such a tale, and he could do

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.