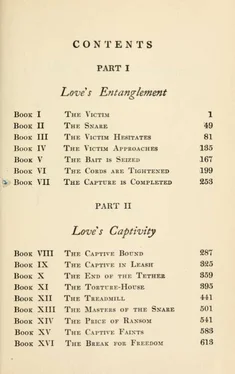

Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

blazed with jewels and silver and gold. Here were the masters of the metropolis, the masters of life; the dispensers of patronage—that "public" which he had to please. He would bring his vision and lay it at their feet, and they would give him or deny him opportunity! And what was it that they wanted? Was it worship and consecration and love? One could read the answer in their purse-proud glances; in the barriers of steel and bronze with which they protected the gates of their palaces; in the aspects of their flunkeys, whose casual glances were like blows in the face. One could read the answer in the pitiful features of the little errand-girl who went past, carrying some bit of their splendor to them; or of the ragged beggar, who hovered in the shelter of a side-street, fearing their displeasure. No, they were not lovers of life, and protectors; they were parasites and destroyers, devourers of the hopes of humanity! Their splendors were the distilled essence of the tears and agonies of millions of defeated people —their jewels were drops of blood from the heart of the human race!

§ 5. So, with rage and bitterness, Thyrsis was gnawing out his soul in the night-time; distilling those fierce poisons which he was to pour into the next of his works —the most terrible of them all, and the one which the world would never forgive him.

There came another episode, to bring matters to a crisis. In the far Northwest lived another branch of Thyrsis' family, the head of which had become what the papers called a "lumber-king". One of this great man's radiant daughters was to be married, and the family made the selecting of her trousseau the occasion for a flying visit to the metropolis. So there were

family reunions, and Thyrsis was invited to bring his wife and call.

Corydon voiced her perplexity.

"What do they want to see us for?" she asked.

"I belong to their line," he said.

"But—you are poor!" she exclaimed.

"I know," he said, "but the family's the family, and they are too proud to be snobbish."

"But—why do they ask me?"

Thyrsis pondered. "They know we have published a book," he said. "It must be their tribute to literature."

"Are they people of culture?" she asked.

"Not unless they've tried very hard," he answered. "But they have old traditions—and they want to be aristocratic."

"I won't go," said Corydon. "I couldn't stand them."

And so Thyrsis went alone—to that same temple of luxury where he had called upon the college-professor. And there he met the lumber-king, who was tall and imposing of aspect; and the lumber-queen, who was verging on stoutness; and the three lumber-princesses, who were disturbing creatures for a poet to gaze upon. It seemed to Thyrsis that he had been dwelling in the slums all his life—so sharp was the shock which came to him at the meeting with these young girls. They were exquisite beyond telling: the graceful lines of their figures, the perfect features, the radiant complexions; the soft, filmy gowns they wore, the faint, intoxicating perfumes that clung to them, the atmosphere of serenity which they radiated. There was that in Thyrsis which thrilled at their presence—he had been born into such a world, and might have had such a woman for his mate.

But he put such thoughts from him—he had made his

gns

choice long ago, and it was not the primrose-path. Perhaps he was over-sensitive, acutely aware of himself as a strange creature with no cuffs, and with hardly any soles to his shoes. And all the time of these women was taken up by the arrival of packages of gowns and millinery; their conversation was of diamonds and automobiles, and the forthcoming honeymoon upon the Riviera. So it was hard for him not to feel bitterness; hard for him to keep his thoughts from going back to the lonely child-wife wandering about in the park—to all her deprivations, her blasted hopes and dying glories of soul.

The family was going to the matinee; as there w T as room in their car, they asked Thyrsis to go with them. So he watched the lumber-king (who had refused to lend him money, but had offered him a "position") draw out a bank-note from a large roll, and pay for a box in one of Broadway's great palaces of art. And now— having been advised so often to study what the public wanted—now Thyrsis had a chance to recline at his ease and follow the advice.

"The Princess of Prague", it was called; it was a "musical comedy"; and evidently exactly what the public wanted, for the house was crowded to the doors. The leading comedian was said by the papers to be receiving a salary of a thousand dollars a week. He held the center of the stage, clad in the costume of a lieutenant of marines, and winked and grinned, and performed antics, and sang songs of no doubtful significance, and emitted a fusillade of cynical jests. He was supposed to be half-drunk, and making love to a runaway princess—who would at one moment accept his caresses, and then spurn him coquettishly, and then execute an unlovely dance with him. In between these di-

verting procedures a chorus would come on, a score or so of highly-painted women, hopping and gliding about, each time clad in new costumes more cunningly indecent than the last.

From beginning to end of this piece there was not a single line of real humor, a spark of human sentiment, a gleam of intelligence; it was a kind of delirium tremens of the drama. To Thyrsis it seemed as if a whole civilization, with all its resources of science and art—its music and painting and costumes, its poets and composers, its actors, singers, orchestra, and audience—had all at once fallen victims to an attack of St. Vitus' dance. He sat and listened, while the theatre full of people roared and howled its applause; while the family beside him—mother and father and daughters— laughed over jokes that made him ashamed to turn and look at them. In the end the realization of what this scene meant—not only the break-down of a civilization, but the trap in which his own spirit was caught—made him sick and faint all over. He had to ask to be excused, and went out and sat in the lobby until the "show" was done.

The family found him there, and the bride-to-be inquired if he "felt better"; then, looking at his pale face, an idea occurred to her, and after a. bit of hesitation, she asked him if he would not stay to dinner. In her mind was the conflict between pity for this poor boy, and doubt as to the fitness of his costume; and Thyrsis, having read her mind in a flash, was divided between his humiliation, and his desire for some food. In the end the baser motive won; he buried his pride, and went to dinner. —And so, as the fates had planned it, the impulse to his next book was born.

§ 6. THERE came another guest to the meal—the rector of the fashionable church which the family attended at home. He was a young man, renowned for the charm of his oratory; smooth-shaven, pink-and-white-cheeked, exquisite in his manners, gracious and insinuating. His ideas and his language and his morals were all as perfectly polished as his finger-nails; and never before in his life had Thyrsis had such a red rag waved in his face. But he had come there for the dinner, and he attended to that, and let Dr. Holland provide the flow of soul; until at the very end, when the doctor was sipping his demi-tasse.

The conversation had come, by some devious route, to Vegetarianism; and the clergyman was disapproving of it. That made no difference to Thyrsis, who was not a vegetarian, and knew nothing about it; but how he hated the arguments the man advanced! For that which made the doctor an anti-vegetarian was an attitude to life, which had also made him a Republican and an Imperialist, a graduate of Harvard and a beneficiary of the Apostolic Succession. Because life was a survival of the fittest, and because God had intended the less fit to take the doctor's word as their sentence of extermination.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.