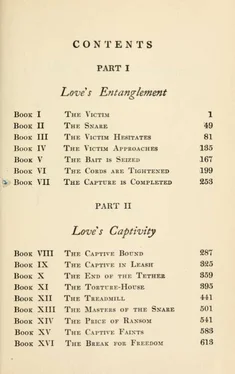

Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

§ 8. THYRSIS paid a week's living expenses to have this manuscript copied; and then he took it about to the publishers. First came his friend Mr. Ardsley, who had become his chief adviser. When Thyrsis went to see him, Mr. Ardsley drew out an envelope from his desk, and took from it the opinion of his reader. "'What in the world is the matter with this boy?'' he read. "That's the opening sentence."

And then he fixed his eyes upon the boy. "What in the world is the matter?" he asked.

Thyrsis sat silent; there was no reply he could make. He was strongly tempted to say to the man, "The matter is that I am not getting enough to eat!"

But already Thyrsis himself had judged "The Higher Cannibalism" and repudiated it. It was born of his pain and weakness, and it was not the work he had come into the world to do. So at the end he had placed

LOVE'S PILGRIMAGE

a poem, which told of a visit from his muse, after the fashion of Musset's "Nuits"; the muse had been sad and silent, and in the end the poet had torn up the product of his hours of despair, and had renewed his faith with the gracious one.

Meantime the long winter months dragged by, and still there was no gleam of hope. For Corydon it was even harder than for her husband. He at least was expressing his feelings, while she could only pine and chafe, without any sort of vent. Her life was a matter of colorless routine, in which each day was like the last, except in increased monotony. She tried hard not to let him see how she suffered; but sometimes the tears would come. And her unhappiness was bad for the child, which in the beginning had been robust and mag^ nificent, but now was not growing properly. Thyrsis would have ridiculed the idea that nervousness could affect her milk; but the time came when, in later life, he saw the poisons of fatigue and fear in test-tubes, and so he understood why the child had not been able to lift its head until it was a year old, and had then been well on the way to having "rickets."

All their life was so different from the way they had dreamed it! The dream still lured them; but its voice grew fainter and more remote. How were they to keep it real to themselves, how were they to hold it? Their existence was made up of endless sordidness, of dreary commonplace, that opposed them with its passive inertia where it did not actively attack them. "Ah, Thyrsis!" Corydon would cry to him, "this will kill us if it lasts too long!"

For one thing, they no longer heard any music at all. She was not strong enough to practice the piano; and his violin was gone. Here in the great city an end-

less stream of concerts and operas and recitals flowed past; and here were they, like starving children who press their faces against a pastry-cook's window and devour the sweets with their eyes. Thyrsis kept up with musical and dramatic progress by reading the accounts in the papers and magazines; but this was a good deal like slaking one's thirst with a mirage. He used to wonder sometimes if he were to write to these great artists—would they invite him to hear them, or would they too despise him ? He never had the courage to try.

Once in the course of the long winter some one presented Corydon with two tickets to the opera, and they went together, in a state of utter bliss. It was an unusual experience for Thyrsis, for their seats were in the orchestra, and hitherto he had always heard his operas from the upper rows in the fifth balcony, where the air was hot and stifling, and the singers appeared as a pair of tiny arms that waved, and a head (frequently a bald head) that emitted a thin, far-distant voice. This had become to him one of the conventions of the opera; and now to discover the singers as full-sized human beings, with faces and legs and loud voices, was very disturbing to his sense of illusion.

Also, alas, they had not been free to select the opera. It was "La Traviata"; and there was not much food for their hungry souls in this farrago of artificiality and sham sentiment. They shut their eyes and tried to enjoy the music, forgetting the gallant young men of fashion and their fascinating mistresses. But even the music, it seemed, was tainted; or could it be, Thyrsis wondered, that he could no longer lose himself in the pure joy of melody? Many kinds of corruption he had by this time learned about; the corruption of men,

and of women, and of children; the corruption of painting and sculpture, of poetry and the drama. But the corruption of music was something which even yet he could not face; for music was the very voice of the soul—the well-spring from which life itself was derived. Thyrsis thought, as he and Corydon wandered about in the foyers of this palatial opera-house, was there anywhere on earth a place in which heaven and hell came so close together. A place where the lust and pride of the flesh displayed themselves in all their glory; and in contrast with the purest ecstasies the human spirit had attained! He pointed out one rich dowager who swept past them; her breasts all but jostling out of her corsage as she walked, her stomach squeezed into a sort of armor-plate of jewels, her cheeks powdered and painted, her head weighted with false hair and a tiara of diamonds, her face like a mask of pride and scorn. And then, in juxtaposition with that, the Waldweben and the Feuerzauber, or the grim and awful tragedy of the Siegfried funeral-march! There were people in this opera-house who knew what such music meant; Thyrsis had read it in their faces, in that suffocating top-gallery. He wondered if some day the demons that were evoked by the music might not call to them and lead them in revolt, to drive the moneychangers from the temple once again!

§ 9. ANOTHER editor was reading "The Hearer of

O

Truth," and a publisher was hovering on the brink of venturing "The Higher Cannibalism"; and so the two had new hopes to lure them on. When the spring-time had come, they would once more escape from the city, and would put up their tent on the lake-shore! They spent long afternoons picturing just how they would

live—what they would eat, and what they would wear, and what they would study. As for Cedric—so they had called the baby—they saw him playing beneath the big tree in front of the tent. And what fun they would have giving him his bath on the little beach inside the point!

"I'll fix up a clothes-basket for him to sleep in!" declared Thyrsis.

"Nonsense, dear!" said Corydon. "I've told you many times before—we'll have to have a crib for him!"

"But why?" cried he; and there would follow an argument which gave pain to his economical soul.

Corydon declared herself willing to do her share in the matter of saving money; but it seemed to him that whenever he suggested a concrete idea, there would be objections. "We can get up at dawn," he would say, "and save the cost of oil."

"Yes," she would answer.

"And we can do our own laundry," he would continue. But immediately another argument would begin; it was impossible to persuade Corydon that diapers could be washed in cold water, even when one had the whole of the Great Lakes for a washtub.

They would go on to contemplate the glorious time when they would have money enough to build a home of their own, that could be inhabited in winter as well as in summer; Corydon always referred to it with the line from "Caradrion"—"the little cot, fringed round with tender green." It would be fine for the baby, they agreed—he should never have to go back to the city again. Thyrsis had a vision of him as he would be in that home: a brown and freckled country boy, with what were known, in the dialect of "dam-fool talk", as "yagged panties and bare feets".

But Corydon would protest at that picture. "It's all right," she said, "to put up with ugliness if you have to. But what's the use of making a fetish of it?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.