Elisa has just gone off to swap coats with her pal — something suede for something leather, always on the lookout for clothes that will kill her. I feel the same about music. I want to be killed by music; I don’t want music to relax to, I want it to match the grief inside me, the years of weeping in overheated children’s homes as a boy. Beethoven can get there sometimes. But enough of all this, something is going to happen. I want the world to know that I am going to prune the small bay tree in the garden and marry Elisa. We will throw a summer party in our garden and plant a lawn, lush and green from the April city rain.

‘Elisa?’

‘Yes, Joe?’

‘Do you think there is a better way to live than this?’

‘Oh yes. There must be.’

I used to ask the same question of the fat, cross-eyed carers who looked after me in the institutions that became my home after Mom died. They stuffed their mouths all day with stale pink sponge cakes that a local bakery donated to the ‘orphans’, and hit us when we wet our beds or asked questions that were beyond the limits of their minds. Every time they beat me, I chanted a phrase over and over in my head — beautiful breath beautiful breath beautiful breath — and as my mother had predicted, it made things better. Beautiful breath was Elisa, the teenage girl in the dorm across the corridor. Elisa had a secret. At night she crept out of bed and stuck the coloured feathers she had plucked from a duster onto her grey-soled shoes with flour and water.

From the very first moment I saw Elisa, I knew we were destined to marry. The clips she put in her hair made my heart roar. Two green plastic butterflies. They told me she wanted a better way to live, long before she stuck feathers on her shoes.

We dug the soil to sow the grass and now our three cats have paws soaked with mud and everywhere inside the house, on carpets and chairs, are cat-paw prints like fossils you find on rocky beaches. Elisa and I have lived through our own personal ecstasies and catastrophes. When we laze on the old kilim rug my mother bought from somewhere in Persia, our bodies are hesitant and love soaked. The moon is oily, the trees swollen with black blossom against the chemical sky. Although our interior worlds are volcanic, exotic, troubled, the everyday is beautifully predictable. We eat pancakes on Sundays — something I like to cook for Elisa, who secretly prefers toast and Marmite — we read the world press on our screens and Skype our friends. After breakfast we get dressed and browse in flea markets or walk by the river near the luxury flats that used to be warehouses or sit in city parks on benches that dead people have donated to the public. Our favourite inscription reads, ‘I love you Joan from tiny George.’

We made the date for our wedding and carved it into the bark of our bay tree. Elisa whitewashed the wall at the back of the yard and her best friend, Rona, said it looked like a postcard she once saw of a fisherman’s cottage in Greece. Rona rolled up her sleeves and made a soup with one hundred potatoes, sixty cloves of garlic and forty-seven leeks. Rona is very precise about everything. When Elisa asks Rona if there is a better way to live than this, Rona replies, You will have to be more specific about what you regard as ‘this’ and what you regard as ‘that’. While Rona chopped her eighty-third potato into six slices, I made ten tall jugs of margarita and Elisa barbecued plenty of chicken drumsticks over an old oil drum sawed in half. Then we went off to dress for our Big Day.

As I soaked in the bath, I saw a starling through the window, swaying to and fro on the bay tree. Once again, the sad grey childhood shoes my bride decorated with feathers flashed before my eyes, as they have done so often in my adult life. And then I dragged in a vision for a wedding outfit. Yes, while men and women argue on the moon, I will go for the exuberant and baroque. I will swank around my Victorian house with its boarded-up fireplaces and nineteenth-century plumbing in a suit made from tartan and silk. I will comb my black hair already threaded with silver and scent it with rose water from the orchards of Istanbul.

My first glimpse of Elisa was through a haze of smoke from the barbecue. My orphan bride wore a silver mesh dress, lime sandals and yards of eyelashes. Beautiful breath beautiful breath beautiful breath. I loved every part of her. The registrar from Orpington looked us in the eye and said words like Honour and Cherish without blinking. Gnats hovered above the sizzling chicken. Pete and Mike exchanged a lustful look. A car alarm went off.

Elisa said Yes and I said Yes.

We said Yes in all the European languages. Yes. We said yes we said yes, yes to vague but powerful things, we said yes to hope which has to be vague, we said yes to love which is always blind, we smiled and said yes without blinking. I wished my mother could hear us say yes and I thought about the stories she told me when I was a child and walked on garden walls that seemed so high but she always said yes, yes climb up and walk on that wall, I will hold your hand and tell you about the skyscrapers of Chicago.

Elisa and I exchanged rings. The best man and best woman threw rice over our heads. We kissed. We felt each other panic under our wedding clothes as the rice fell to the ground. Perhaps it frightened the starling because it flew away. It had some feathers missing from its neck and one of its eyes had closed up. We were pleased the bird had spotted somewhere better to live but we secretly wanted it to stay. And then we saw that our three cats were hiding in the bay tree and realised it had found a safer place to live.

Elisa and I, the last two smokers on earth, sit under the bay tree, listening to our cats purr while they sharpen their claws and lick each other clean. My new wife plays with my fingers and the sun, which is setting, prints colour into the concrete towerblocks.

Elisa says, ‘Now that we are married, your mother is my mother too.’ Yes, we are orphans groping for things we are connected to, vague and blind things like the cold bright wedding rings on our fingers. While I sit smoking with Elisa, a halo of midges circling her head as she crosses and uncrosses her long legs, I recall for her my mother’s stories which sometimes sound like dreams: Benito Mussolini smiling in a hat with an eagle on it, the Wall Street Crash, a woman staring at a boat in Hiroshima, the Minghetti cigars my father smoked, Elise Davis walking on a fifty-foot high wire holding an umbrella, Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus in the USA the day the buses were no longer segregated, Algerians eating honey cake after they won independence from France, a teenage boy climbing over the Berlin Wall that separated capitalism from communism, a line from a play called Ubu Roi : ‘WELL PERE UBU, ARE YOU CONTENT WITH YOUR LOT?’, Mahatma Gandhi, the Black Panthers, Tom and Jerry, powdered eggs, miners digging deep in the earth for coal.

I press my lips against Elisa’s eyelids and lead her to the honeymoon chamber where I have dimmed the lights and washed the linen. Although my body is stuffed with the gauze of information and the soul has gone out of fashion, I still use plants to heal my wounds and pains. I put calendula ointments on my shins when I fall over and sip chamomile tea when I’m in shock, a flower the Egyptians dedicated to their gods. One day, when Elisa and I are long buried and have turned to dust, I hope a robot boy will find this document and correct my spelling mistakes with his silver fingers. Although he will look nothing like me, he too will be a son without a mother, his eyes open all night long.

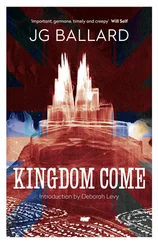

Deborah Levy writes fiction, plays, and poetry. Her work has been staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company and widely broadcast on the BBC, including her dramatizations of two of Freud’s most iconic case histories, Dora and The Wolfman .

Читать дальше