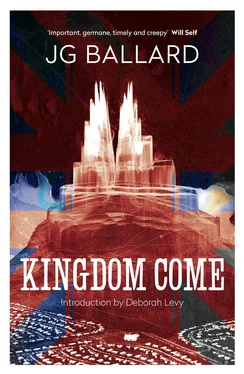

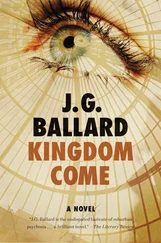

J. G. BALLARD

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

4thestate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2006

Copyright © J. G. Ballard 2006

The right of J. G. Ballard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Introduction copyright © Deborah Levy 2014

Interview copyright © Sarah O’Reilly 2007

‘Remaking the World’ copyright © J. G. Ballard 2007

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover by Stanley Donwood, from a photographic copperplate etching.

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2006 ISBN: 9780007290109

Version: 2014-07-11

Cover Title Page Copyright Introduction by Deborah Levy Part I Chapter One: The St George’s Cross Chapter Two: The Homecoming Chapter Three: The Riot Chapter Four: The Resistance Movement Chapter Five: The Metro-Centre Chapter Six: Going Home Chapter Seven: Snakes And Ladders Chapter Eight: Accidents And Emergencies Chapter Nine: The Beach At The Holiday Inn Chapter Ten: Street People Chapter Eleven: A Hard Night Chapter Twelve: Neon Palaces Chapter Thirteen: Duncan Christie Chapter Fourteen: Towards A Willed Madness Chapter Fifteen: The Prisoner In The Tower Chapter Sixteen: The Bomb Attack Chapter Seventeen: The Geometry Of The Crowd Chapter Eighteen: A Failed Revolution Chapter Nineteen: The Need To Understand Chapter Twenty: The Racing Circuit Chapter Twenty One: A New Politics Part II Chapter Twenty Two: The Trenchcoat Hero Chapter Twenty Three: The Women’s Refuge Chapter Twenty Four: A Fascist State Chapter Twenty Five: Lonely, Lost, Angry Chapter Twenty Six: A Bullet In The Hand Chapter Twenty Seven: An Anxious Intermission Chapter Twenty Eight: The Old Man’s Quest Chapter Twenty Nine: The Stricken City Chapter Thirty: Assassination Chapter Thirty One: ‘Defend The Dome!’ Chapter Thirty Two: The Republic Of The Metro-Centre Part III Chapter Thirty Three: The Consumer Life Chapter Thirty Four: Work Makes You Free Chapter Thirty Five: Normality Chapter Thirty Six: Shrines And Altars Chapter Thirty Seven: Prayers And Wool-Wash Cycles Chapter Thirty Eight: Tell Him Chapter Thirty Nine: The Last Stand Chapter Forty: Exit Strategies Chapter Forty One: A Solar Cult PAPERING OVER THE CRACKS: J. G. Ballard talks to Sarah O’ Reilly REMAKING THE WORLD by J. G. Ballard About the author By the same author About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION BY DEBORAH LEVY

Consumerism rules, but people are bored. They’re out on the edge, waiting for something big and strange to come along … They want to be frightened. They want to know fear. And maybe they want to go a little mad.

J. G. Ballard, Kingdom Come

J. G. BALLARD, our greatest literary futurist, changed the coordinates of reality in British fiction and took his faithful readers on a wild, intellectual ride. He never restored moral order to the proceedings in his fiction because he did not believe we really wanted it. Whatever it was that Ballard next imagined for us, however unfamiliar, we knew we were in safe hands because he understood ‘the need to construct a dramatically coherent narrative space’.

When I was a young writer in the 1980s, Ballard first came to my attention after I read his luminous, erotic story collection, The Day of Forever . It was so formally inventive that I would not have guessed it had been published in 1967. Nor did I know that the baffled conservative literary establishment of his generation had tried to see off his early work as science fiction. Ballard always insisted he was more interested in inner space than outer space.

When it came to anything by Ballard, genre really did not matter to me; his fiction could have been filed under Tales of Alien Abduction or Marsh Plants and I would have hunted it down. Despite our difference in generation, gender and literary purpose, it was clear to me that he and I were both working with some of the same aesthetic influences: film, Surrealist art and poetry, Freud’s avant-garde theories of the unconscious. I was just starting to write but Ballard made me feel less lonely. Perhaps more significantly we shared the dislocation of not being born in Britain. Home was the imagination. I too was attracted to the paintings of de Chirico and Delvaux, with their dreamplaces – empty, melancholy cities, abandoned temples, broken statues, shadows, exaggerated perspectives. Ballard was going to make worlds we had not seen before in British fiction. When asked, after the success of Empire of the Sun , why it took him so long to write in a less disguised way about his childhood experience at the internment camp in Lunghau, his beautiful answer was that is took him ‘twenty years to forget and twenty years to remember’. Of course, images from Shanghai and the war were laid forever inside him. I have always thought that his books, with the exception of Crash , which seems to me an abstract attempt to grieve for his dead wife, were already written in that one room he shared with his parents between 1943 and 1945. The reach of his imagination was never going to fit with the realist literary mainstream but I was always encouraged by his insistence that he was an imaginative writer.

I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend death, to charm motorways, to ingratiate ourselves with birds, to enlist the confidences of madmen.

Good on you Jim.

There is a great deal of rather strained legend-making when it comes to Ballard, but it is the witty, deadpan, open-minded American journalist and pianist, V. Vale, founder of the tremendous RE/Search Publications and champion of Ballard since 1973, who in my view tracked his thought drifts most sensitively in various interviews. I have never regarded Ballard as a kind of psychogeographer of postmodernity; his most enjoyable fiction is more Dada than Debord.

I believe in the impossibility of existence, in the humour of mountains, in the absurdity of electromagnetism, in the farce of geometry, in the cruelty of arithmetic, in the murderous intent of logic.

His highly imagined landscapes and abandoned aircraft and stopped clocks and desert sand were located in his head – and anyway he preferred driving fast cars to walking. He once sent me a photograph of the Heathrow Hilton and told me it was his spiritual home.

What was it that Ballard offered to me as a young female writer? It is more to do with what he did not offer. He preferred social theory to social realism. I was not going to run to Ballard’s books to learn how to write a ‘well rounded’ character, for God’s sake. His characters are more like tannoys to broadcast his arguments and ideas. But I did love his gloomy, unbelievable male psychiatrists, cinematically lit, groomed, suave and perverse, sipping a stiff gin and tonic in towelling robes while they observe (and possibly medicate) everyone else freaking out around them. The well-mannered narrators in the later novels ( Cocaine Nights , Super-Cannes , Millennium People , Kingdom Come ) are mostly mild, middle-class, manly men. Their destiny is to become inflamed Nietzschean men, excited to finally understand that they too would like to punch their fists through the boredom of the empty, greedy, good life with its fragile veneer of civilisation. Yet I have always regarded Ballard as quite a humane writer, a paternal writer, steering us through the ruins of his dystopias via the mindset of his apparently rational avatars – always endearingly baffled to discover their own suppressed urges.

Читать дальше