“Are you asking me a personal question?” he inquired with explicit annoyance.

“Let’s call it a personal question,” replied Firmino bravely.

“And why do you ask this question?” insisted the lawyer.

“Because you don’t believe in anything,” Firmino burst out, “I get the impression that you don’t believe in anything.”

The lawyer smiled. Firmino felt that he was ill at ease.

“I might, for example, believe in something that to you seems insignificant,” he answered.

“Give me a convincing example,” said Firmino. He had got himself into this and wanted to keep up his role.

“For example a poem,” replied the lawyer, “just a few lines, it might seem a mere trifle, or it might also be a thing of the essence. For example:

Everything that I have known

You’ll write to me to remind

Me of, and likewise I shall do ,

The whole past I’ll recount to you .

The lawyer fell silent. He had shoved away his plate and sat fumbling with his napkin.

“Hölderlin,” he went on, “it’s a poem called Wenn aus der Ferne , which means ‘If From the Distance,’ it’s one of his last. Let us say that there might be people who are waiting for letters from the past, do you think that a plausible thing to believe in?”

“Perhaps,” replied Firmino, “it might be plausible, though really I’d like to understand it a bit more.”

“Nothing to it,” murmured the lawyer, “letters from the past which give us an explanation of a time in our life which we have never understood, an explanation whatever it might be that enables us to grasp the meaning of the years gone by, a meaning that eluded us then, you are young, you are waiting for letters from the future, but just suppose that there are people waiting for letters from the past, and maybe I am one of these, and maybe I go so far as to imagine that one day I shall receive them.”

He paused, lit one of his cigars, and asked: “And do you know how I imagine they will arrive? Come on, try and think.”

“I haven’t the faintest idea,” said Firmino.

“Well,” said the lawyer, “they will arrive in a little parcel done up with a pink bow, just like that, and, scented with violets, as in the most trashy romantic novels. And on that day I shall lower my horrible old snout to the package, undo the pink bow, open the letters, and with the clarity of noonday I shall understand a story I never understood before, a story unique and fundamental, I repeat, unique and fundamental, such a thing as can happen but once in our lives, that the gods grant only once in our lives, and to which at the time we did not pay enough attention, for the simple reason that we were conceited fools.”

Another pause, longer this time. Firmino watched him in silence, taking stock of his fat old droopy cheeks, his almost repulsively fleshy lips, and the expression of one lost in memories.

“Because,” the lawyer went on in a low voice,“ que faites-vous faites-vous des anciennes amours? . It’s a line from a poem by Louise Colet, and goes on like this: les chassez-vous comme des ombres vaines? Ils ont été, ces fantômes glacés, coeur contre coeur, unepart de vous même* There’s no doubt the lines were addressed to Flaubert. I should add that Louise Colet wrote very bad poems, poor dear, even if she thought of herself as a great poetess and wanted to make a hit in all the literary salons in Paris, really mediocre stuff, no doubt about it. But these few lines really get to one, it seems to me, because what in fact do we do with our past loves? Push them away in a drawer along with our socks full of holes?”

He looked at Firmino as if expecting confirmation, but Firmino said not a word.

“Do you know what I say,” continued the lawyer, “that if Flaubert didn’t understand her then he was really a fool, in which case we have to agree with that smarty-pants Sartre, but maybe Flaubert did understand, what do you think, did Flaubert understand or not?”

“Maybe he understood,” replied Firmino, “I couldn’t say offhand, maybe he did understand but I’m not in a position to swear to it.”

“I beg your pardon, young man,” said the lawyer, “but you claim to be studying literature, indeed that you intend to write a paper on literature, and you here own up to me that you can’t say anything for sure on the fundamental question, whether Flaubert did or did not understand Louise Colet’s coded message.”

“But I’m studying Portuguese literature in the 1950s,” Firmino defended himself, “and what has Flaubert to do with Portuguese literature in the 1950s?”

“Apparently nothing,” said the lawyer, “but only apparently, because in literature everything has to do with everything else. Look, young man, it’s like a spider’s web, you know what a spider’s web is like? Well think of all those complicated threads woven together by the spider, all of which lead to the center, looking at those at the outer edge you wouldn’t think it, but everything leads to the center, I’ll give you an example, how could you understand L’éducation sentimentale , a novel so terribly pessimistic and at the same time so reactionary, because according to the criteria of your friend Lukács it is terribly reactionary, if you don’t know the tasteless novelettes of that period of appalling bad taste that was the Second Empire? And along with this, making the proper connections, what if you were to be unaware of Flaubert’s state of mental depression? Because, you know, when Flaubert was shut up there in his house at Croisset, peering out at the world through a window, he was fearfully depressed, and all this, even though it seems not so to you, forms a spider’s web, a system of underground connections, of astral conjunctions, of elusive correspondences. If you want to study literature at least learn that you must study correspondences.”

Firmino gave him a look and tried to come up with an answer. Strangely enough he was seized with that same absurd sense of guilt the owner had caused him when he had told him what was on the menu.

“I try in all humility to concern myself with Portuguese literature in the 1950s,” he replied, “without getting all swollen-headed about it.”

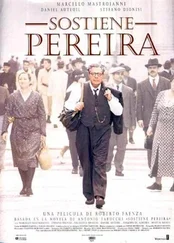

“Right,” said the lawyer, “without getting swollen-headed you have to plumb the depths of that particular period. And to do so perhaps you ought to know the weather reports published in the Portuguese papers during those years, as you may learn from a magnificent novel by one of our own authors who succeeded in describing the censorship imposed by the political police by referring to the weather reports in the papers, do you know the book I mean?”

Firmino didn’t answer but moved his head in a noncommittal fashion.

“Well then,” said the lawyer, “I give you that as a clue to a possible line of research, so remember, even weather reports can come in handy as long as they are taken as metaphors, as clues, without falling into the sociology of literature, do I make myself clear?”

“I think so,” said Firmino.

“Sociology of literature my foot!” repeated the lawyer with an air of disgust, “We live in barbarous times.”

He made to rise to his feet and Firmino leapt to his so as to get there first.

“Put it all on my bill, Manuel,” called out the lawyer, “our guest enjoyed his lunch.”

They wended their way out, but the lawyer stopped in the doorway.

“This evening I’ll let you know something about what position Torres adopts,” he said, “I’ll send you a message at Dona Rosa’s. But it is essential for you to interview him tomorrow and for your paper to bring out another special edition, since you are running so many special editions about this severed head, have you got me?”

Читать дальше