“Why not tell Uncle Sarazin what’s on your mind? Do you think I want to shoot you?”

“That’s for you to know.”

“You’re wrong. Not yet. A pity they didn’t enrol you in our youth organization. You’d have learnt to fire a gun, or how to use a hand grenade. These things shouldn’t be put off. Were you in some youth association — when you were still at home?”

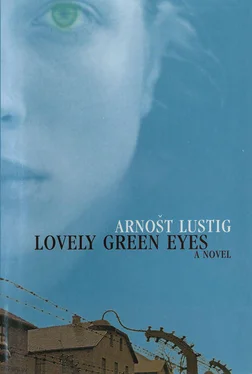

She could not say that she didn’t remember. But she didn’t want to trap herself. Surely he had asked her this question already? How was he testing her and what did he hope to discover?

“I used to go on school outings.”

From the age of ten she had been in the Jewish Girl Guides. They went on outings along the banks of the Vltava, to the Davie reservoir. For a second she saw the rock face under which they had erected their tents and made their camp fire. They would sing Czech and Zionist songs. None of them had been to the Promised Land. In the evenings they were taught to recognize the stars, during the day they went out into the woods and read signs or learnt to orient themselves with a compass. They had swimming and running races. Once she came first in the 400 metres. They shared anything they had brought along; they called it a commune. Everything was still ahead of them. Life was comprehensible then, the future was far away and good. She remembered every minute of it.

“Our young people know from earliest childhood what a dagger is, or a pistol, or a hand grenade. It’s the responsibility of the parents. At eighteen the boys put on a uniform and join the Waffen-SS or the Volunteer SS. They learn to operate anti-aircraft guns. Some as young as sixteen. They disdain death — that is the test. They do sentry duty at air-raid shelters, they guard factories and sewers to prevent saboteurs from damaging them. They disdain death because they love Germany. Killing is part of basic education, of basic morality. You’d better hurry and catch up with what you’ve missed. I know what I’m talking about.”

She remained silent.

“Two things are all you need — fire and a pistol,” he added. “The third is loyalty. Suppose you had to defend yourself? Or defend me?”

“We have guards here, watchtowers with machine guns, guard dogs,” she said carefully. “We’re protected by a wall. We’re here on your territory.”

He looked into her green eyes.

“I’m just like all the rest,” she said weakly.

He looked at his Luger with admiration and gratitude, with what he would call love and loyalty; something she didn’t understand and could explain to herself only by the power that the weapon lent him, the superiority it gave him. It frightened her, as did everything in which she could not orientate herself and against which she had no defence. She sensed the danger in her whole being. She watched him looking at his pistol. She was waiting for what he was going to say or do next.

Did she lack something the others had? Could she catch up or put it right if she didn’t know what it was?

She thought of Big Leopolda Kulikowa’s advice to accept everything as normal, even the most unexpected and the most eccentric. Hadn’t the Madam told them that people satisfied themselves in any way they could, even with ducks, sheep and bitches? She must hold on to what she could.

She fixed her gaze on his eyes. She didn’t know what would happen next. He was lying on his side, supported by his elbow, holding the gun with his finger on the trigger. Before her eyes was the whiteness that comes to those sentenced to death. Did it matter whether he shot her as a Jewess or as a whore with whom he had failed, or both? In her mind she wrestled with that invisible difference.

At the same time, she felt like that little girl she had seen on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, under the arc-lamps, which were swinging in the wind. The girl had been separated from her parents and her brother. Crowds of people walked past her. Then a woman invited her to join her. The little girl didn’t move. The woman took her by the hand and included her with her own family. All four of them came up before the doctor in the middle of the ramp. With a jerk of his thumb he sent them to the gas chamber.

What was going to happen now did not depend upon her. In her mind she backed away, into some kind of tunnel, where she might hide, where she might escape. The whiteness before her spread out like a fog, white blossoms on unfamiliar shrubs, a kind of warming light snow. The Obersturmführer confused her. She didn’t understand what he’d meant by a test of cowardice. She was as bewildered as the people on the ramp after arriving in sealed wagons at Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was holding his gun — his finger on the trigger, aimed at her chest. If he was trying to scare her, he had succeeded.

“Head up,” the Obersturmführer instructed her. “Sit straight. Lean against the bed. Don’t slouch. Pull your legs up, so you keep them to yourself and not near my toes. I want you to see the whole of me.”

She did as he told her.

“That’s better.”

They were now like pictures on a playing card, one at the top and the other at the bottom. She tried to lower her head so she wouldn’t seem taller than him. She was looking at his chest, not his face. Was he going to shoot her now? She could see the cubicle window out of the corner of her eye.

“Do you see me?”

“I see you.”

“Why are you lowering your eyes?”

She raised them.

He held the pistol out to her.

“Take it.”

“Why?”

“Do what I’m telling you. It’s only a piece of metal. It won’t bite.”

“I don’t know how to handle it.”

“Not kennt kein Gebot.” Needs must when the devil drives.

What need was he talking about? Why did he want her to take his pistol? So he could accuse her of something she hadn’t done?

“Do I have to beg you? Do as I say!”

She was afraid. If she extended her hand would the Obersturmführer change his grip on the pistol, slip his finger through the trigger guard and pull the trigger? Did she have to do what he demanded so he could shoot her when she reached out as if she had wanted to seize the pistol? Was it to be like in the camp when Rottenführer Schratz snatched the caps off prisoners, tossed them to the fence, and shot the prisoners when, on his orders, they ran to retrieve them? Did Obersturmführer Sarazin know which camp she had come from? He could have found out from The Frog.

He leant forward with the pistol. She knew it was a trap, that she would not live to play the scene out to its end. The livid scar on the Obersturmführer’s forehead had turned the colour of blood. He was concentrating on something that must be important to him, something that accelerated his pulse. They would know just as little about her as they did about Krikri. Just as nobody knew who Big-Belly was. Suddenly she felt close to both of them. She thought of Captain Hentschel’s green pullover. Of his — now her, though not for long — 30 marks. Those who might mourn her were no longer alive. Above all she felt weary now.

“We are both cold-blooded,” he said. “We are all cold-blooded animals.”

Had he changed his mind about his game with the gun or was he merely prolonging it?

“Do you hear me? Take the pistol.”

Her back was pressed against the wood of the bed. Were his eyes getting moist?

“Do as I’m telling you!”

“I’m doing what you say.”

“I’m not used to being argued with. Take it!”

He spoke as if he were giving orders to a dog after throwing it a bone. She half shut her eyes. She pressed her hands to her chest. Perhaps he would shoot her in the head and not between her legs. She felt the fatigue of her father. She felt something going numb inside her.

Читать дальше

![Корнелл Вулрич - Eyes That Watch You [= The Case of the Talking Eyes]](/books/32103/kornell-vulrich-eyes-that-watch-you-the-case-of-thumb.webp)