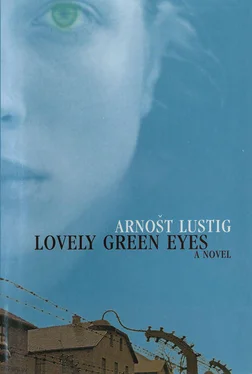

Arnost Lustig

Lovely Green Eyes

For Eva and all who are and will be with her.

A. L.

To the memory of my mother, one of the millions who perished in the Holocaust.

E. O.

How many people have secrets that no-one ever discovers?

From early morning, units of the Waffen-S S had been arriving. They had demanded an extension of the shift until 4 p.m.

Fifteen: Hermann Hammer, Fritz Blücher, Reinhold Wuppertal, Siegfried Fuchs, Bert Lippert, Hugo Redinger, Liebel Ulrich, Alvis Graff, Siegmund Schwerste! Herbert Gmund, Hans Frische, Arnold Frey, Philipp Petsch, Mathias Krebs, Ernst Lindow.

For the past three days the frost had been severe. The pipes in the former agricultural estate had burst when the water in them froze. The girls had been provided with two new tubs, but the water froze rock hard in these too. The river had frozen over. Iron rusted, steel fractured. Once or twice a train halted by the bridge because its engine’s boilers had burst. Inside, the plaster in the building developed mould and the walls of the cubicles turned black with soot from the stoves. The waiting room and the canteen, with its long table for 60 people, were no better. The living quarters resembled a bacon-curing shop.

Overnight the walls had acquired a crest of snow, like a chefs white hat pushed up from his forehead. At dawn, when the blizzard was over, when the wind had blown away the clouds and it was no longer snowing, it looked as if what lay on the ground was blood. For a few minutes the snow was steeped in purple and ruby red. An invisible silence hung over the landscape.

Inside, along the corridor, an inscription in spiky Gothic letters (the flashes of the S S insignia were ancient runes) declared: We were born to perish .

The silence was broken by a truck or a bus making for the field brothel. From the distance, from between the sky and the ground, came the rumble of artillery.

She had woken in the middle of the night. She had pain between her legs. Before her eyes and in her ears was the Pole who’d stood at the ramp in Auschwitz-Birkenau when they’d stumbled from the trains — the deep, chesty voice of a broad-shouldered soldier of the Kanada squad who, over and over, had ordered the mothers to give the children to their grandmothers.

“Don’t ask why. Do it now!”

Having passed the doctors at the end of the long line who sent people either to the left or to the right, she had arrived at the Frauenkonzentrationslager and there understood the meaning of the order.

“Give the children to their grandmothers”.

The old women and the children had gone straight from the ramp to the gas chambers.

This is the story of my love. It is about love almost as much as it is about killing; about one of love’s many faces: killing. It is about No. 232 Ost, the army brothel that stood in the agricultural estate by the River San before the German army retreated further west; about 21 days, about what a girl of 15 endured; about what it means to have the choice of going on living or of being killed, between choosing to go to the gas chamber or volunteering to work in a field brothel as an Aryan girl. It is about what memory or oblivion will or will not do.

I fell in love with Hanka Kaudersovâ’s smile, with the wrinkles of a now 16-year-old, with the effect her face had on me. What saves me, apart from the uncertainty of it, is time. There are fragments out of which an event is composed, there are its colours and shades. And there is horror.

On that last day before the evacuation of No. 232 Ost, before they put Madam Kulikowa up against the back wall a few steps from the kitchen, and the first salvo shattered her teeth, she’d said that deep down she had expected nothing better.

Twelve: Karl Gottlob Hain, Johann Obersaltzer, Wilhelm Tietze, Arnold Köhler, Gottfried Lindner, Moritz Krantz, Andreas Schmidt, Granz Biermann, Garolus Mautch, August Kreuter, Felix Körner, Jorgen Hofer-Wettermann.

In my mind I can hear Madam Kulikowa introducing Skinny Kaudersovâ to No. 232 Ost on that first Friday morning … Anything that is not specifically permitted is forbidden. (This was something Skinny already knew from the Frauenkonzentrationslager at Auschwitz-Birkenau.) Regulations are posted on the cubicle doors. The soldier is always right. Kissing is forbidden. Unconditional obedience is demanded. You must not ask for anything.

“Any perks we share equally,” Madam Kulikowa said, with both uncertainty and cunning. “A man is like a child and generally behaves like one. He expects to get everything he wants. He will expect you to treat him unselfishly, like a mother.”

She urged her to think of pleasanter things.

Oberführer S chimmelpfennig had ordered the following notice to be posted on the doors of the cubicles, in the waiting room and in the washroom.

With immediate effect, it is forbidden to provide services without a rubber sheath. Most strictly prohibited are: Anal, oral or brutal intercourse; To take urine or semen into the mouth or anus; To re-use contraceptives.

During roll-call one day, Oberführer S chimmelpfennig threatened to import Gypsy women to the estate. He knew of at least five brothels in Bessarabia where they were employed. “No-one here is indispensable,” he said.

Twelve: Heinrich Faust, Felix Schellenberg, Fritz Zossen, Siegfried Skarabis, Adolf Seidel, Günther Eichmann, Hans Scerba, Rudolf Weinmann, Hugon Gerhard Rossel, Ernst Heidenkampf, Manfred Wostrell, Eberhardt Bergel.

In the evening, as they were sweeping by the gate which carried the German eagle, Skinny arranged the snow into symmetrical piles, and wondered whether she was punishing herself for being alive. What had become of Big-Belly, from whom she’d inherited Cubicle No. 16 and a pot for heating water and a small cask? Where was Krikri? Or Maria-Giselle? The first two had gone to the wall, the third to the “Hotel for Foreigners” at Festung Breslau. Here, as Oberführer S chimmelpfennig put it, Skinny was serving her apprenticeship. What kind of girl was Beautiful? Or Estelle, Maria-from-Poznan, Long-Legs, Fatty, Smartie and the others? What was the name, or the nickname, of the girl who died at two in the morning three days after Schimmelpfenning’s botched attempt at an appendectomy?

“If you don’t sleep you’ll feel like death warmed up in the morning,” said Estelle later that night. “You won’t change anything by not sleeping.”

There was fresh snow. A train with troops on home leave rattled across the steel bridge over the river.

“This is what it must be like in the Bering Straits,” Estelle said. “Except for those wintering, there isn’t a soul about.”

Skinny had never heard of the Bering Straits.

“Twenty-four hours of darkness every day. An ocean of ice,” Estelle said.

“How deep is it?” Skinny wanted to know. “Never mind. Go to sleep.”

Suddenly Estelle said: “Do you think anybody knows the truth?”

“About what?”

“About you. About me. About the Oberführer or Madam Kulikowa.”

“My head is spinning,” said Skinny. “I have to get some sleep.”

“My memory is failing me,” Estelle said.

“You should be grateful.”

“Why?”

“Because.”

Skinny’s eyes were falling shut. In a moment she would be asleep. It was cold and she would be frozen stiff by the morning. In the cubicle, with a soldier, it was at least warm, but the Oberführer did not allow the girls’ dormitories to be heated. They could nestle up to each other, he’d said. Skinny fell asleep thinking of the Frauenkonzentrationslager at Auschwitz-Birkenau, when she was still with her mother and her father. Before her father had thrown himself against the high-voltage fence and her mother was taken away at a selection parade. Her brother had gone to the gas chamber straight from the ramp.

Читать дальше

![Корнелл Вулрич - Eyes That Watch You [= The Case of the Talking Eyes]](/books/32103/kornell-vulrich-eyes-that-watch-you-the-case-of-thumb.webp)