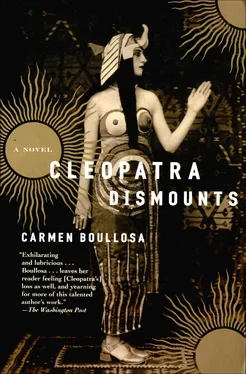

Is it a concern that poets put their ink at the service of Augustus’s memory? Horace showed no reluctance to do it, convinced as he was of the vileness of the woman who dared defy Rome. Propertius neither. But Virgil, far wiser — I say it without disrespect for his other virtues, since it isn’t wisdom that makes a poet great — Virgil did feel an enormous regret at the end of his life. Because he gratuitously vilified Cleopatra and overpraised Octavius, he intended to burn his epic. Lying did not trouble him so long as he was blinded by the power radiating from victorious Caesar. Perhaps it was not clear to him that he was lying, for, as I said, he was blinded. But over time the blindness gave way to sight; he grasped the real size of the man, the so-called hero, creature of cunning, but he glimpsed also the man’s disfiguring flaws and his degrading weaknesses. He understood finally that, in piling mud on the memory of Egypt’s queen, he had extinguished a star. Remorse overwhelmed him. Like me, he did not want to go to the grave, laden with regrets, for he well knew the power of the Egyptians in the Land of the Dead. I, too, have no wish to die in regretful silence. I fear, as he did, as anyone would, to encounter in the kingdom of the dead the righteous rage of Cleopatra in all her arrogance. (Horace and Cicero were right about her on that point.)

Nobody is infallible. My queen was not. She erred considerably in not cultivating the poets of Italy. She thought them inferior men, ignorant fellows whose “hands were not fit to wash the clothes of Egyptians,” to quote her words. She offered examples like that clumsy verse from Cicero:

O fortunatam natam me constile Romani

considering it a prime example of dull-witted mediocrity, and held it up as the yardstick by which to measure the poetic endeavors of Rome. She made no effort to woo the poets; in fact, she never disguised her contempt for them, confident that, back in Egypt, there were brilliant poets with scrolls enough to describe her worth, dozens of docile hands eager to eulogize her. Was she justified in her assessment of Roman poetry? Did she hit the mark when she described Julius Montanus, Macrobius, Varius Rufus, and Sulpicius of Carthage as “a bunch of plodding mediocrities”? Probably. But she missed the mark in not trying to win them over to her cause, in the hope that they might reward her by faithfully honoring her memory. Toward Cicero she behaved with unprecedented arrogance. The first time he approached her, he used the pretext of lending her a learned text in order to pursue some pettifogging lawsuit and to ingratiate himself with the wife of Caesar and the queen of Egypt. It was out of sheer disdain for Cicero that she made him a promise she had no intention of keeping. Amonius tells us so.

What was that promise? To take him back to Egypt as her guest so that, in a series of letters, he could describe the country for a Roman audience. The conditions he laid down for his trip were such as to guarantee him enough drachmas to buy himself yet another palace. Of the letters themselves, little could be expected, for he had added a provision to the contract: “Whatever I may write will be at the service of freedom and truth alone, and no one will be permitted to assess it before I have it circulated and placed in the hands of the copyists, for I submit to no censorship. .” The deal he requested was that Cleopatra make him rich twice over and in return he would write whatever he pleased, most probably to satisfy an enemy of Cleopatra, who would reward him by doubling his riches yet again. He had inherited considerable wealth and added to it by marrying well. He further augmented it by his cleverness and his well-chosen friendships. My advice to Cleopatra would have been: “What does it matter? Give him enough to buy a palace. You lose nothing.” But either I would not have dared to say it or it simply did not occur to me to say it back in those palmy days. Neither I nor anyone else of the court spoke up. Sarapion, a member of the royal cabinet since the days of Ptolemy Auletes, only worsened relations between her and Cicero. One afternoon, they say, Serapion was looking for Atticus, who was staying at Cicero’s palace, when he bumped into Cicero himself. Deferentially, Cicero asked if he could be of service. Insolently Sarapion snapped back: “I’m looking for Atticus!” Not one word of greeting. No courteous conversation. It’s no wonder that Cleopatra and her court received such sour commentary in all the writings of Cicero.

Thanks to these oversights, Cleopatra is doomed to be remembered in Roman letters as a general’s whore, as a “book-monger” (as they term the mean female slaves here who assign work to even meaner slaves), or a cruel stepmother bent on murdering the previous sons of her husband — calumny stops at nothing! But it is too late now for these facile regrets. She should have thought twice before making such enemies. But even then she might have failed to win them over, not simply because of the loyalty of the poets to Rome and to Augustus, but because “who can tolerate a woman with all the virtues?”

I have taken so much time in getting back to her genuine voice that you may think I am dodging the issue. It isn’t so. And even if it were, I have a duty to gather my forces in order to recapture freely, without fear of the consequences, that rich, complex voice in all its nuances, before I take my final steps into the world beyond. And now here they are. The exact words of Cleopatra, as dictated to me in the last hours of her life:

Damn the day I left my refuge with the pirate band in Cilicia! Damn the day I returned to Alexandria, those days when I studied and grew into a woman! Damn you too, Demetrius! I always respected you as my teacher, for it was you who initiated me into the mysteries of womanhood that made me what I was and what I was to become after my defeat. Damn you, because before I learned your lessons, I was invulnerable. At eleven years old, nothing could harm me. I was whole and entire, my own possession, untouched by knowledge. My life would have turned out better, if I had remained by the side of my pirates, if I had stayed as I was, if I had stopped my heart from learning the feelings of a woman. I wish I could start over on my journey to earth and remain there in beautiful Tarsus, living among but aloof from its sailors and warriors, defending myself against the knowledge of its sages. Damn those who brought me to this idiotic defeat! Damn myself for wanting to be queen of the world. Damn Rome! And above all, damn the legs of every Roman male, the handsome as well as the ugly, damn the lot of them! Note, Diomedes, this is the history of my time with the Cilician pirates, with whom I should have stayed, to whom I really belonged. This is the story of how I ran away to be with them, and I want to focus on that runaway child. I want the name of Cleopatra to be preserved in her, in that jewel case of vitality and joy.

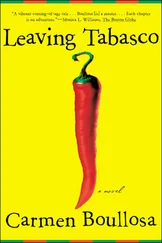

That self-seeking tribune, Publius Clodius Pulcer! His nickname among gossipers was “the Sacrilegious.” At a ritual in honor of the Bona Dea, which only women were allowed to attend, at the time when Caesar was the urban proctor, Clodius dressed as a woman and slipped into the meeting, hoping to satisfy his lust for Caesar’s wife. He was detected but, thanks to a young slave girl called Habra, he escaped. Anyway, he used to claim, this glory-grabbing tribune, that he had made a proposal in the Senate to dole out wheat to the mob, legally and at no cost to them, with the idea of winning their adoration. The measure had no precedent. The economy of Rome could not support such a subsidy. So he came up with a shortcut to bolster Rome’s finances. He asked the Senate to approve the annexation of Cyprus. His main pretext, among a dozen others, was that King Ptolemy, the brother of Auletes, was in league with the pirates of Cilicia and was allowing them to use his territory as a sanctuary. “I have been a victim of the pirates of Cilicia,” he began his harangue (and here he was telling the truth, because years before they had ransacked some of his property). “I consider the repeated mockery from Cyprus to be an insult to Rome.” And so on. The Senate approved the measure, the army was dispatched, and Cyprus fell into Roman hands. Auletes did nothing to help his brother. The Egyptians, already resentful of their king because of his earlier concessions to Rome, exploded in rebellion. Before we knew it, my father was toppled from his throne and we had to flee in haste from Alexandria.

Читать дальше