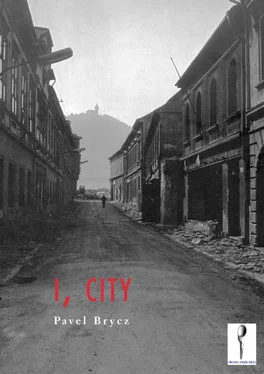

Pavel Brycz - I, City

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pavel Brycz - I, City» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2006, Издательство: Twisted Spoon Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:I, City

- Автор:

- Издательство:Twisted Spoon Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I, City: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «I, City»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dubliners

I, City

I, City — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «I, City», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At the time of the relocation of the church, many of its relics and other Baroque valuables were transferred to a small chapel in the nearby village of Vtelno, famous for the late 19th-century flowering of its apple orchards. The region between Vtelno and Most was soon filled, populated post-industrially, with an oppressive orchard of gas stations, warehouses and shopping centers that grew, and soon wilted, amid the pre-fabricated concrete apartment blocks ( paneláky ) that were the glory of communist architecture. By contrast, the attractive villas of the Zahražany quarter (the location of the area known as “Na Špačkárně” — “At the Starling House”), situated at the foot of Hněvín, were constructed at the beginning of last century. At that European fin de siècle , this city, too, was in its own, if modest, cultural heyday. German money financed numerous structures in the styles of the pseudo-Renaissance, Art Nouveau and Beaux Arts. These are now among the oldest surviving buildings in Most, rendering the city — architecturally, as well in many other respects — one of the “newest” cities in all of Bohemia. Moravia’s Brno can boast centuries-old churches and castles. “Golden” Prague hosts its “hundred spires” and the ruins of antiquity. In contrast, and the church complex aside, Most has a handful of faded buildings dating from around the year 1900, and then mile after mile of gray concrete.

As late as 1900, the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants of Most were still of Germanic origin. However, with the extension of the train track from Ústí nad Labem to Chomutov, which served to unite Most’s mines with greater Bohemia, the Czech population of the city grew steadily, eventually comprising more than one quarter of Most’s inhabitants by the time of the First World War. By then, large German corporations had long appeared on the scene and had succeeded in converting the mining process from the underground “canary-in-a-cage” style to modern open-cutting, which much like quarrying requires enormous holes to be created in the surface of the earth. The owners and management were German, the machinery was German, but the workers were predominantly Czech, having come as west as their borders allowed to essentially destroy their own city in the enrichment of foreigners. It was at this time, leading up to the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, that Most began to be redeveloped from a so-called “boom” town of individualistic miners (think of the Yukon, or Klondike) into a major incorporated mining center. Heavy industry was its governance, and money, little of which became reinvested in Most, was its law.

In 1938, the Germans broke ground in nearby Záluží, situated between Most and Litvínov — the hometown of hockey idols Hlinka, Lang, Ručinský, Svoboda, and Šlégr — and built a chemical plant as part of the multinational Hermann Goering Werke to produce gas from the mined lignite; tens of thousands of slave laborers were worked there day and night. In 1945, nearly all the German citizens of Most were expelled under the infamous Beneš Decrees, and Czechs from all over the country began to arrive en masse, many forcibly resettled there for work purposes after 1948 by the new communist government (as referenced in this volume in “An Appearance, Manly”); they moved into the abandoned houses of Old Most, the villas in Zahražany, and the dilapidated neighboring tenements. Today, this plant manufactures oil, and pollutes the air for miles in every direction, depending on wind.

As mentioned, a plan was conceived in the 1960s to completely destroy the buildings of Old Most in order to exploit the earth underneath for its rich deposits. The idea was to level all the buildings, change the course of the Bílina riverbed (here affectionately called the Běla), and to build an enormous expanse of panel-houses around the expansion of the city (“I’m a city of reinforced concrete”) in order to accommodate the majority of newly arrived citizen-workers, in the process institutionalizing oppression in the establishment of a wildly disastrous, misguidedly ultra-modern, city center. Among its many other faults, this plan greatly over-designed Most. The New Most was intended to accommodate one-hundred-thousand citizens, but Most’s population at its height had been only seventy thousand. Most New or Old, much emptiness is still there. Altogether, thirty-four municipalities in the area of Most have thus far been destroyed in the pursuit of polluting, inefficient lignite — these include the pre-industrial villages such as Židovice, Libkovice, Ervěnice, Kopisty (the liquidation of this last village interrupted the ancient continuity of settlement between Most and Litvínov). And so Pavel Brycz writes in the voice of the city he’s chronicling: “I am a city, a new city. I cannot bear witness to the past,” for how can a city bear witness to a life predating its very existence, a life it was in many ways created to destroy? “Kde domov můj?” Brycz quotes elsewhere, “Where is my home?” — the first words of the Czech anthem, the song of a nation that for too long existed only in hope. As Brycz asks this question, so does his city. Where to find a city’s home if not in itself, of itself, among its own people?

I, City — the first ever full-length English translation of Pavel Brycz’s work — is many things. A collection of stories. Of prose-poems. A novel-in-stories. A series of sketches in the best easterly European tradition of Danilo Kiš, or Isaac Babel. Formal and topical inspiration can most convincingly be found in the Czech literature Brycz holds closest to his heart: the poetry of mid-century writers like Václav Hrabě and Josef Kainar (both of whom wrote texts that were to be much used as rock lyrics); Karel Konrád (1899–1971) is an essential precursor, especially in his trilogy Robinsonáda, Rinaldino and Dinah , a pastiche of prose and poetry that lovingly chronicles the first loves and comings-of-age of adolescent boys in Bohemia. Additionally, Karel Poláček’s bucolic-humorous children’s book, Bylo nás pět [We Made Five], is referenced here if not as a model for Brycz’s work then as a model for Most’s budding poets. As Brycz makes fictional people say factual things and factual people (Franz Kafka, John Paul II, the last Czechoslovak communist president Gustáv Husák) say fictional things, post-modernity via Gabriel García Márquez and other so-called Magical Realists makes its almost requisite — though noiseless — appearance.

Though Brycz’s ideal is a curious sort of anthropomorphism, proposing to make his city talk, it seems the “I” purporting to be Most is much larger than anything that can be contained on a map — almost an entire consciousness, at enough of a remove from the town itself that he, she, or it can observe and can know seemingly everything, past and present. The “I” is a view not from below, which is the view of the earth, scarred beneath the city, but from above, which is the view of the transcendent, of heaven. If Brycz’s “I” is to be terrestrial, though, it must be an “I” released, set free, seemingly risen from the land, which has been defiled in man’s pursuit of power, to ascend high above Most’s people, in order to narrate their lives, and the life of their city, from the vantage of a simpler, more hopeful future — even as the concrete panel-houses tower, too, dwarfing the spires of the Deacon’s Church, in man’s strained attempt at the divine.

But narration here is no straightforward affair. Brycz doesn’t actually write about the people of Most, as it would seem. If pre-industrial Realism is the standard, there are no “real people” in Brycz’s text; it’s almost as if Brycz is implying it’s impossible for “real people” to survive in Most. Rather, these mostly silent, shy and lonely beings (the Hrabalian denizens of the Liars’ Bench aside) seem frozen in time, petrified, oftentimes placed in the background of any action, which is overwhelmingly historical, or an action of memory. They lose their color, fading into black and white, ghosts slowly dragging themselves on the most mundane of errands through the sooty streets. Their horror is not immediate. The one Nazi in this book does not seem particularly evil; no one in these pages gets deported to labor or re-education camps. But the horror is surely there, a cancer buried like coal. Concomitantly, Brycz never describes Most as Most, Most as a whole. Rather, his gaze lights on individual lives, on discrete histories that resist any civic coherence. Most seems like an abandoned place at the end of the world, a planet unto itself suspended in the polluted void, surrounded by “non-existence” — symbolized best in the “real world” by the Romany (Gypsy) ghetto on the outskirts of town. This area, located in the Chanov district, would be home to “the petite Gypsy woman” (if Gypsy she is), Dezider Balogh the boxer and champion urinator, and the thieves who kill and eat the dog at the villa in Zahražany, which itself is a metaphor for Most’s post-communist reconstruction. Built in the 1980s especially for Most’s Romany as “compensation for the unsatisfactory housing in Old Most,” Chanov, a square of ruinous panel-houses, contains great poverty. It seems almost totally ungoverned even today. Public drunkenness is the norm. Unemployment is just short of total. Beyond these outskirts is Niemandsland , no-man’s land, marked only by the Krušné hory, the Ore Mountains, over which — it is rumored — one would find Germany.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «I, City»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «I, City» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «I, City» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.