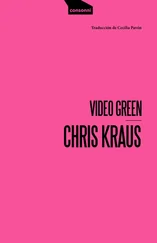

In Paris in the ’50s, upwardly mobile ghetto Jews like Sylvère Lotringer suffered a terrible dinner party dilemma: whether to announce the fact that they were Jews to offset possible racial slurs and jokes and be accused of arrogantly ‘flaunting it;’ or say nothing and be accused of deviously “hiding it.” Kitaj the slippery Kike is never just one thing and so people think he’s tricking them.

It amused me that Kitaj has wrapped himself around the idea of creating “exegesis” for his art, writing texts to parallel each painting. “Exegesis”: the crazy person’s search for proof that they’re not crazy. “Exegesis” is the word I used in trying to explain myself to you. Did I tell you, Dick, I’m thinking of calling all these letters The Cowboy and the Kike ? Anyhow, I felt I had to see the show.

The exhibition was presented by the Met with a huge amount of explication that served to distance Kitaj further from his viewers and his peers. Curatorial excitement mixed with apprehension: how to make this “difficult” work accessible? By introducing us to the artist as an admirable freak.

Entering the exhibition, the viewer encounters the first in a series of large-scale placards explaining Kitaj’s strange career. A sentimental pen-and-ink portrait of the not-yet-dead artist is displayed beside a text describing biographic landmarks. Kitaj grew up in Troy, New York and ran away at age 16 to be a merchant seaman. He enlisted in the Army, then attended art school in Oxford on the GI Bill. After school he moved to London, painted, showed. After the unexpected death of his first wife in 1969, Kitaj stopped painting for several years. This fact is disclosed in a tone of awed surprise. (Why has every single life that deviates from the corporate norm—from high school to an east coast BA, followed by a California art school MFA, followed by a cheerful steady flow of art-production—become so oddly singular?)

The placards in the second room continue amplifying Kitaj’s oddness. He is “a voracious reader of literature and philosophy” “a bibliophile.” The facts of Kitaj’s life are sketched so bare that he becomes exotic, mythic. The text is telling us that while it may be impossible to love the artist or his work we must admire him. Although his work is “difficult,” it has a substance and a presence; it can’t be entirely dismissed; it holds its own. And so at 62, in his first major retrospective, Kitaj becomes revered/reviled. All the rightness of his work is undermined by singularity. He’s a talking dog domesticated into myth.

(Am I being too sensitive? Perhaps, but I’m a kike. And isn’t it well-documented that those kikes who don’t devote themselves to power-mongering and money-grubbing are hopelessly highstrung?)

The placards go on to apologize/explain Kitaj’s prose. After years of fucked-up readings of his work, he was forced to write his own. The placard suggests you spend some money to access Kitaj’s texts (buy the catalogue, rent the audiocassette) but in reality you don’t have to. Because in the middle of the second room there’re multiple copies of the catalog displayed on two long library tables complete with shaded reading lamps and chairs. How perfect—a tiny architectural slice of the New York Public Library or Amsterdam’s grand American Hotel. (You too can be a kike!) This display was so archaic that the catalogs weren’t even chained, and I contemplated stealing one, though finally I didn’t. Because although Kitaj’s friends include some of the greatest poets in the world, I didn’t like his texts that much. His texts spoke to someone not quite real, the “perplexed but sympathetic viewer.” You either like the paintings or you don’t. Kitaj’s writing pandered so it was disappointing.

But Kitaj’s paintings never pander and they aren’t disappointing.

My first favorite, painted in 1964, was called The Nice Old Man and The Pretty Girl (With Huskies) . What a terrific painting to own! What a lot it says about your life circa 1964 if you were somebody significant in the art world! It’s a painting that’s seduced by the frenetic energy and glamour of this time while mocking it.

The colors of this painting—mustard yellow, Chinese red and forest green—were high fashion in their time. The nice old man sits facing us in 3/4 profile from the depths of a mauve Le Corbusier-inspired chair. The Nice Old Man’s head has been replaced with a side of ham that makes him look like Santa Claus. Over it, he wears a gas mask. The chair is expediently correct, Roche-Bobois, but not remarkable or beautiful. Perhaps chosen by an uninspired decorator. The Nice Old Man’s body extends across almost the entire frame, ending in one of those Nordic furtrimmed boots that go in, though mostly out, of style. And this boot is pointed squarely at the knee ( Claire’s Knee by Eric Rohmer?) of the Pretty Girl, who is completely headless. Her coat is Chanel red and almost matches the Nice Old Man’s seedy Santa outfit. Except it’s better cut—tight at the top, then flaring. Her dress is mustard orange.

And then there’re those huskies , visitors from a David Salle work that’s travelled back in time, panting, grinning, moving, even though each is trapped inside a white rectangle, towards a snow-bank rising from the bottom right corner of the frame. Between them there’s a red square displaying some of their possessions: a model of a monolith for him, a Gucci scarf for her. What a modish pair. And what could be more modish than Kitaj’s acerbic portrait of them? Except that the acerbic-ness seems to go too far, beyond the effervescent skepticism of the period towards a moral irony that lays it bare.

And, perfectly, appropriately to that first adrenaline rush of art & commerce that characterized the art world in 1964, the painting’s circle of meaning is completed by its ownership. Nice Old Man was loaned to the exhibit by its owners Susan and Alan Patricoff, prominent members of the mid-’60s New York City/East Hampton art and social scene. Alan Patricoff, a venture capitalist, art collector and early owner of New York magazine is a great supporter of Kitaj’s. According to the writer Erje Ayden, he and Susan Patricoff gave the most amazing parties in East Hampton, where writers, art-world luminaries and miss-outs mixed with famous socialites.

And what an edgy choice this painting must’ve been: a painting that both disparages and contains the witty effervescence of that scene. As if to say, they’re capable of taking an ironic distance from their values and their fame, this scene they made; powerful and secure enough to pat the mouth that bites the hand that feeds it. It’s deadpan wit with cynicism at its core. And isn’t it cynicism that makes the money, while enthusiasm spends? To buy such cynicism confirms that Patricoff was no consumer, but a highly self-reflexive creator of this scene. Nice Old Man draws an outside circle around the giddiness and wit that characterized Pop Art, a movement read by some as the closest thing the art world’s come to Sophisticate Utopia. It’s a painting, finally, for victors, reminding us that there’re winners & losers in every game.

LATER—

Oh D, it’s Thursday morning 9 a.m. and I feel so emotional about this writing. Last night I “replaced” you with an orange candle because I felt you weren’t listening anymore. But I still need for you to listen. Because—don’t you see?—no one is, I’m completely illegitimate.

Right now Sylvère is in Los Angeles at your school making $2500 for talking about James Clifford. Later on tonight you’ll have a drink and he’ll drive you to the plane, because you’re about to speak in Europe. Did anybody ask me my ideas about Kitaj? Does it matter what they are? It’s not like I’ve been invited, paid to speak. There isn’t much that I take seriously and since I’m frivolous and female most people think I’m pretty dumb. They don’t realize I’m a kike.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу