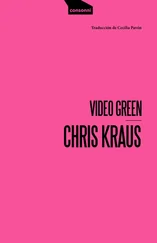

I want to thank the following people who helped with their encouragement and conversation: Romy Ashby, Jim Fletcher, Carol Irving, John Kelsey, Ann Rower and Yvonne Shafir.

Thanks also to Eryk Kvam for legal counsel, Catherine Brennan, Justin Cavin and Andrew Berardini for proofreading and fact-checking, editors Ken Jordan and Jim Fletcher, Marsie Scharlatt for insights and information on the misdiagnosis of schizophrenia; and Sylvère Lotringer as always for everything.

PART 1: SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE

December 3, 1994

Chris Kraus, a 39-year-old experimental filmmaker and Sylvère Lotringer, a 56-year-old college professor from New York, have dinner with Dick ——, a friendly acquaintance of Sylvère’s, at a sushi bar in Pasadena. Dick is an English cultural critic who’s recently relocated from Melbourne to Los Angeles. Chris and Sylvère have spent Sylvère’s sabbatical at a cabin in Crestline, a small town in the San Bernardino Mountains some 90 minutes from Los Angeles. Since Sylvère begins teaching again in January, they will soon be returning to New York. Over dinner the two men discuss recent trends in postmodern critical theory and Chris, who is no intellectual, notices Dick making continual eye contact with her. Dick’s attention makes her feel powerful, and when the check comes she takes out her Diners Club card. “Please,” she says. “Let me pay.” The radio predicts snow on the San Bernardino highway. Dick generously invites them both to spend the night at his home in the Antelope Valley desert, some 30 miles away.

Chris wants to separate herself from her coupleness, so she sells Sylvère on the thrill of riding in Dick’s magnificent vintage Thunderbird convertible. Sylvère, who doesn’t know a T-bird from a hummingbird and doesn’t care, agrees, bemused. Done. Dick gives her copious, concerned directions. “Don’t worry,” she interrupts, flashing hair and smiles, “I’ll tail you.” And she does. Slightly buzzed and keeping the accelerator of her pickup truck steady, she’s reminded of a performance she did called Car Chase at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project in New York when she was 23. She and her friend Liza Martin had tailed the steelily good-looking driver of a Porsche all the way through Connecticut on Highway 95. Finally he’d pulled over to a rest stop, but when Liza and Chris got out he drove off. The performance ended with Liza accidentally-but-really stabbing Chris’ hand onstage with a kitchen knife. Blood flowed, and everyone found Liza dazzlingly sexy and dangerous and beautiful. Liza, belly popping out of a fuzzy midriff top, fish-net legs tearing up against her green vinyl miniskirt as she rocked back to show her crotch, looked like the cheapest kind of whore. A star is born. No one at the show that night had found Chris’ pale anemic looks and piercing gaze remotely endearing. Could anyone? It was a question that’d temporarily been shelved. But now it was a whole new world. The request line on 92.3 The Beat was thumping, Post-Riot Los Angeles, a city strung on fiber optic nerves. Dick’s Thunderbird was always somewhere in her line of sight, the two vehicles strung invisibly together across the concrete riverbed of highway, like John Donne’s eyeballs. And this time Chris was alone.

Back at Dick’s, the night unfolds like the boozy Christmas Eve in Eric Rohmer’s film My Night At Maud’s . Chris notices that Dick is flirting with her, his vast intelligence straining beyond the po-mo rhetoric and words to evince some essential loneliness that only she and he can share. Chris giddily responds. At 2 a.m., Dick plays them a video of himself dressed as Johnny Cash commissioned by English public television. He’s talking about earthquakes and upheaval and his restless longing for a place called home. Chris’ response to Dick’s video, though she does not articulate it at the time, is complex. As an artist she finds Dick’s work hopelessly naive, yet she is a lover of certain kinds of bad art, art which offers a transparency into the hopes and desires of the person who made it. Bad art makes the viewer much more active. (Years later Chris would realize that her fondness for bad art is exactly like Jane Eyre’s attraction to Rochester, a mean horse-faced junky: bad characters invite invention.) But Chris keeps these thoughts to herself. Because she does not express herself in theoretical language, no one expects too much from her and she is used to tripping out on layers of complexity in total silence. Chris’ unarticulated double-flip on Dick’s video draws her even closer to him. She dreams about him all night long. But when Chris and Sylvère wake up on the sofabed the next morning, Dick is gone.

December 4, 1994: 10 a.m.

Sylvère and Chris leave Dick’s house, reluctantly, alone that morning. Chris rises to the challenge of extemporizing the Thank You Note, which must be left behind. She and Sylvère have breakfast at the Antelope IHOP. Because they are no longer having sex, the two maintain their intimacy via deconstruction: i.e., they tell each other everything. Chris tells Sylvère how she believes that she and Dick have just experienced a Conceptual Fuck. His disappearance in the morning clinches it, and invests it with a subcultural subtext she and Dick both share: she’s reminded of all the fuzzy one-time fucks she’s had with men who’re out the door before her eyes are open. She recites a poem by Barbara Barg on this subject to Sylvère:

What do you do with a Kerouac

But go back and back to the sack

with Jack

How do you know when Jack

has come?

You look on your pillow and

Jack is gone…

And then there was the message on Dick’s answerphone. When they came into the house, Dick took his coat off, poured them drinks and hit the Play button. The voice of a very young, very Californian woman came on:

Hi Dick, this’s Kyla. Dick, I—I’m sorry to keep calling you at home, and now I’ve got your answering machine and, and I just wanted to say I’m sorry how things didn’t work out the other night, and—I know it’s not your fault, but I guess all I really wanted was just to thank you for being such a nice person…

“Now I’m totally embarrassed,” Dick mumbled charmingly, opening the vodka. Dick is 46 years old. Does this message mean he’s lost? And, if Dick is lost, could he be saved by entering a conceptual romance with Chris? Was the conceptual fuck merely the first step? For the next few hours, Sylvère and Chris discuss this.

December 4, 1994: 8 p.m.

Back in Crestline, Chris can’t stop thinking about last night with Dick. So she starts to write a story about it, called Abstract Romanticism . It’s the first story she’s written in five years.

“It started in the restaurant,” she begins. “It was the beginning of the evening and we were all laughing a bit too much.”

She addresses this story, intermittently, to David Rattray because she’s convinced that David’s ghost had been with her last night for the car ride, pushing her pickup truck further all the way up Highway 5. Chris, David’s ghost and the truck had merged into a single unit moving forward.

“Last night I felt,” she wrote to David’s ghost, “like I do at times when things seem to open onto new vistas of excitement—that you were here: floating dense beside me, set someplace between my left ear and my shoulder, compressed like thought.”

She thought about David all the time. It was uncanny how Dick had said somewhere in last night’s boozy conversation, as if he’d read her mind, how much he admired David’s book. David Rattray had been a reckless adventurer and a genius and a moralist, indulging in the most improbable infatuations nearly until the moment of his death at age 57. And now Chris felt David’s ghost pushing her to understand infatuation, how the loved person can become a holding pattern for all the tattered ends of memory, experience and thought you’ve ever had. So she started to describe Dick’s face, “pale and mobile, good bones, reddish hair and deepset eyes.” Writing, Chris held his face in her mind, and then the telephone rang and it was Dick.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу