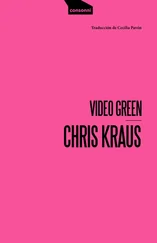

To perform yourself inside a role is very strange. The clothes, the words, prod you into nameless areas and then you stretch them out in front of other people, live.

Chris/Gabi was a mess, persona-less, trying to lose herself in talking. Her eyes were open but afraid, locked in neutral, not knowing whether to look in or out. While she was in rehearsal for the play, Chris had started having sadomasochistic sex with the downtown Manhattan luminary Sylvère Lotringer. This happened about twice a week at lunchtime and it was very confusing. Chris would arrive at Sylvère’s Front Street loft after doing errands on Canal Street. She’d be ushered into Sylvère’s bedroom, walls lined with books and African water bags and whips and he’d push her down onto the bed with all her clothes on. He held her, squeezed her tits until she came. He never let her touch him, often he wouldn’t even fuck her and after awhile she stopped wondering who this person even was, revolving on his bed deeper through time tunnels into memories of childhood. Love and fear and glamour. Browsing through his books she realized she was up against some pretty stiff competition, reading some of the inscriptions: “To Sylvère, The Best Fuck In The World (At Least To My Knowledge) Love, Kathy Acker.” Afterwards they’d eat clam soup and talk about the Frankfurt School. Then he showed her to the door…

So what was Chris performing? At that moment she was a picture of the Serious Young Woman thrown off the rails, exposed, alone, androgynous and hovering onstage between the poet-men, presenters of ideas, and actress-women, presenters of themselves. She wasn’t beautiful like the women; unlike the men, she had no authority. Watching Chris/Gabi I hated her and wanted to protect her. Why couldn’t the world I’d moved around in since my teens, the underground, just let this person be?

“You are not beautiful but you are very intelligent,” the Mexican gigolo says to the 38-year-old New York Jewish heroine of the film A Winter Tan. And of course it’s at that moment that you know he’s going to kill her.

All acts of sex were forms of degradation. Some random recollections: East 11th Street, on the bed with Murray Groman: “Swallow this mother ’til you choke.” East 11th Street, in the bed with Gary Becker: “The trouble with you is, you’re such a shallow person.” East 11th Street, up against the wall with Peter Baumann: “The only thing that turns me on about you is pretending you’re a whore.” Second Avenue, the kitchen, Michael Wainwright: “Quite frankly, I deserve a better-looking, better-educated girlfriend.” What do you do with the Serious Young Woman (short hair, flat shoes, body slightly hunched, head drifting back and forth between the books she’s read)? You slap her, fuck her up the ass and treat her like a boy. The Serious Young Woman looked everywhere for sex but when she got it it became an exercise in disintegration. What was the motivation of these men? Was it hatred she evoked? Was it some kind of challenge, trying to make the Serious Young Woman femme?

* * *

2. The Birthday Party

Inside out

Boy you turn me

Upside down and

Inside out

—late ’70s disco song

Joseph Kosuth’s 50th birthday party last January was reported the next day on Page 6 of the New York Post . And everything was just as perfect as they said: about 100 guests, a number large enough to fill the room but small enough for each of us to feel among the intimates, the chosen. Joseph and Cornelia and their child had just arrived from Belgium; Marshall Blonsky, one of Joseph’s closest friends and Joseph’s staff had been planning it for weeks.

Sylvère and I drove down from Thurman. I dropped him off outside the loft, parked the car and arrived at Joseph’s door at the same moment as another woman, also entering alone. Each of us gave our names to Joseph’s doorman. Each of us had names that weren’t there. “Check Lotringer,” I said. “Sylvère.” And sure enough, I was Sylvère Lotringer’s “Plus One” and she was someone else’s. Riding up the elevator, checking makeup, collars, hair, she whispered, “The last thing you want to feel before walking into one of these things is that you’re not invited,” and we smiled and wished each other luck and parted at the coat-check. But luck was something that I didn’t feel much need of because I had no expectations: this was Joseph’s party, Joseph’s friends, people, (mostly men, except for female art dealers and us plus-ones) from the early ’80s art world, so I expected to be patronized and ignored.

Drinks were at one end of the loft; dinner at the other. David Byrne was wandering across the room as tall as a Moorish king in a magnificent fur hat. I stood next to Kenneth Broomfield at the bar and said a tentative hello; he hissed and turned away. A tighter grip around the scotch-glass, standing there in my dark-green Japanese wool dress, high heels and makeup… But look! There’s Marshall Blonsky! Marshall greets me at the bar and says that seeing me reminds me of the party we attended some 11 years ago when I was Marshall’s date. And of course he would remember because the party was given by Xavier Fourcade to celebrate the publication of Marshall’s first book, On Signs, at Xavier’s Sutton Place town-house. It was late winter, early spring, Aquarius or Pisces and I remember guests tripping past the caterers and staff to walk around the green expanse of daffodils and bunny lawn that separated us from the river. David Salle was there, Umberto Eco was there, together with a stable-load of Fourcade’s models and a reviewer from the New York Times .

At that time I was living in a tenement on Second Avenue and studying charm as a possible escape. Could I be Marshall Blonsky’s perfect date? I’d given up trying to be as sexual as Liza Martin but I was small-boned, thin, with a New Zealand accent trailing off to something that sounded vaguely mid-Atlantic. Perhaps something could be done with this? By then I’d read enough that no one guessed I’d never been to school. Marshall and I’d been introduced by our mutual friend Louise Bourgeois. I loved her and he was fascinated by her iron will and growing fame. “It is the ability to sublimate that makes an artist,” she told me once. And: “The only hope for you is marrying a critic or an academic. Otherwise you’ll starve.” And in the interest of saving me from poverty, Louise had given me, for this occasion, the perfect dress: a straight wool-boucle pumpkin-colored shift, historically important, the dress she’d worn accompanying Robert Rauschenberg to his first opening on East 10th… Most of Marshall’s friends were men—critics, psychoanalysts, semioticians—and he liked that he could walk me round the room and I’d perform for them, listening, cracking jokes in their own special languages, guiding the conversation back to Marshall’s book. So French New Wave… Being weightless and gamine, spitting prettily at rules and institutions, a talking dog without the dreariness of a position to defend.

Dear Dick, It hurts me that you think I’m “insincere.” Nick Zedd and I were both interviewed once about our films for English television. Everyone in New Zealand who saw the show told me how they liked Nick better ’cause he was more sincere. Nick was just one thing, a straight clear line: Whoregasm , East Village gore ’n porn, and I was several. And-and-and. And isn’t sincerity just the denial of complexity? You as Johnny Cash driving your Thunderbird into the Heart of Light. What put me off experimental film world feminism, besides all it’s boring study groups on Jacques Lacan, was its sincere investigation into the dilemma of the Pretty Girl. As an Ugly Girl it didn’t matter much to me. And didn’t Donna Haraway finally solve this by saying all female lived experience is a bunch of riffs, completely fake, so we should recognize ourselves as Cyborgs? But still the fact remains: You moved out to the desert on your own to clear the junk out of your life. You’re skeptical of irony. You are trying to find some way of living you believe in. I envy this.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу