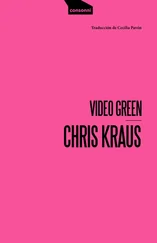

Christians believe in the redemptive power of suffering. It’s the basis of the whole religion. Jesus was frailty personified, his life the Ur-text of suffering, betrayal and abandoned dreams. The suffering of Jesus teaches us that God understands. I don’t see any advantage in believing this. Kikes would rather side-step the whole question of redemption. They think that suffering brings knowledge but knowledge is just a step out into the world. Redemption’s meaningless because there’s nowhere else to go, as humans we’re all locked into the orbit of a life together.

“Jews don’t like images,” I said, explaining some of Sylvère’s work to you that evening in the restaurant, “because images are charged. They rob people of their power. Believing in the transcendental power of the image and its Beauty is like wanting to be an Abstract Expressionist or a Cowboy.” And isn’t undermining this the basis of Kitaj’s most successful work? His best paintings subvert the power of their image by tossing them around in a critical, cerebral mix. It’s through an act of will—collision, contradiction, that these paintings attain their power. Kitaj infiltrates the image in the same way certain Jews lived through World War 2 with phony passports. Kitaj the Sneaky Kike bluffs his way into the Host Culture, Painting, and turns it back upon itself. He paints to challenge iconography.

My father’s favorite writer is William Burroughs.

This morning, after dreaming about dead turtles, I wrote this in my notebook:

My entire state of being’s changed because I’ve become my sexuality: female, straight, wanting to love men, be fucked. Is there a way of living with this like a gay person, proudly?

* * *

One painting in this show maybe has the answer. There’s a Peter Handke story where a youngish German couple drive around America through the desert looking for the famous Hollywood director John Ford. They’ve lost the drift of why they were together, have no idea how to continue with their lives. (In Idaho last summer, Sylvère and I felt this way too.) The German couple thought John Ford would have the answer. (Sylvère and I never looked to anybody, though, for answers, except maybe the idea of you.) John Ford figured they were crazy. He didn’t want to be anybody’s saint, though in this particularly sentimental story he turns out to be.

Peter Handke and Kitaj must’ve known the same John Ford, likeably garrulous and ugly, the kind of guy who thinks that to be alive is to be in charge.

In this painting, John Ford on his Deathbed (1983/84) , John Ford is sitting up presiding over his own deathbed, fully dressed, holding his rosary like a stopwatch and smoking a cigar.

It’s a brilliant and theatrical painting, art-directed like a Mexican-shot Western with its deep blue walls and straw-planked floors, color so strong it reconfigures the painting’s Euro-American script.

There’re several separate scenes within this painting. These scenes are dissonant, but not strategically oppositional. The painting is a chronicle of a life’s events, like the Medieval story paintings that prefigured comic books but these events are splayed like life, chaotic and abstracted. All the dissonance is drawn together in a frame that can contain them not through magic but through Ford’s formidable self-invented will.

At the bottom of the painting we see a scene from John Ford’s past: a man of boundless middle-age talking through a megaphone to actors costumed as poor immigrants in what must’ve been a Texas western—cobblers making cowboy boots. His legs are crossed, his broad face, oblivious to its own ugliness, is partly covered by dark glasses and a squat black hat. In the middle of the painting a matador, maitre’d or major domo holds an empty frame pierced by a salmon pink pole, the kind you’d see on a restaurant patio or in a dancehall. A dancing couple spread their arms around it, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (sort of) painted by Chagall. And there’re lights strung through the painting, extending out into the room, flesh-pink, like the lobster terrace restaurants in La Bufadora, Mexico. The painting frame above Ford’s bed is partly Mexican too, its green-red-yellow frame hanging askew, though its subject is decidedly European: a solitary man in black carrying something through the gray-white snow. It’s pogrom-land, it’s an old television movie.

In this painting dissonance’s disappeared and been reborn as elevated schtick. It’s a grand finale, the production number, where all the show’s motifs come back as jokes. And Kitaj-as-Ford delivers, like movies’re supposed to do, a dazzling punchline: at the upframe center of Ford’s blue wall there’s an Ed Ruscha knock-off framed in black that reads

THE

END

and below it, a tiny painting, window opening out from deep blue walls to deep blue sky. There is no road to immortality but there’s a porthole to it. In this painting objects, people, dance and move but still there’s flesh and weight. Transcendence isn’t only lightness; it’s attained by will.

And why do we crave lightness so?

Lightness is a ’60s lie, it’s Pop Art, early Godard, The Nice Man and the Pretty Girl (With Huskies) . Lightness is the ecstacy of communication without the irony, it’s the lie of disembodied cyberspace.

Through his medium John Ford, Kitaj is telling us that matter moves but you can’t escape its weight. The dead come back to dance not as spirits but as skeletons.

* * *

DD,

On December 3, 1994 I started loving you.

I still do.

Chris

SYLVÈRE AND CHRIS WRITE IN THEIR DIARIES

EXHIBIT A: SYLVÈRE LOTRINGER

Pasadena, California

March 15, 1995

“Gave Proust seminar and first lecture today at Dick’s school. One more to go. Dick was direct and friendly, though in the car I suddenly had flashes of his hand going across Chris’ cunt. Images. The whole situation is so weird. In any case, Chris once again has pulled a fast one. Even though Dick’s rejected her, she’s managed to cover all the bases: She doesn’t need him to respond for her love to go on. She can maintain a relationship with me, draw inspiration from Dick for her work, and even put her film into a vault without pushing it any further.

Chris faxed me her piece about Kitaj, the “kike” painter she identifies with. It’s very heady, spiralling around his idiosyncratic life, critical rejection, East Hampton in the ’60s. I’ve never heard of him, but she manages to weave everything in, including her own present predicament.

I felt very moved by it, exhilarated. Chris now believes that the failure of Gravity & Grace was “destiny,” pushing her towards some further explication of all the emotion within her films. She’s writing without any destination or authority, unlike Dick, who’s off to give another talk in Amsterdam and never writes unless he’s asked to; unlike me, about to give my Evil lecture, collect my check and go home.

And yet Chris was feeling very sad, cut off from Dick, and I was sad too after talking to her. The situation was hopeless: she loved him, needed him, couldn’t stand the idea of not being close to him or communicating with him. I decided I will talk to Dick tomorrow night on our drive out to the airport. I don’t know how he’ll take it; after all, he’s been quite clear about ending this ambiguous situation. And yet if I happened to be heard by him, that would kill me: the idea of a strong connection between the two of them that excludes me. I ended up sobbing until 2 a.m., unable to fall asleep, feeling pretty down and desperate.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу