The moment came.

“Thank you, Julia, thank you for everything.”

He did not say, Let’s keep in touch, send each other e-mails, talk on the phone from time to time. No, he said nothing. But I knew what his silence spelled out, loud and clear. Don’t call me. Don’t contact me, please. I need to figure my entire life out. I need time and silence, and peace. I need to find out who I now am.

I watched him walk away under the rain, his tall figure fading into the busy street.

I folded my palms over the roundness of my stomach, letting loneliness ebb into me.

WHEN I CAME HOME that evening, I found the entire Tézac family waiting for me. They were sitting with Bertrand and Zoë in our living room. I immediately picked up the stiffness of the atmosphere.

It appeared they had divided into two groups: Edouard, Zoë, and Cécile, who were on “my side,” approving of what I had done, and Colette and Laure, who disapproved.

Bertrand said nothing, remaining strangely silent. His face was mournful, his mouth drooping at the sides. He did not look at me.

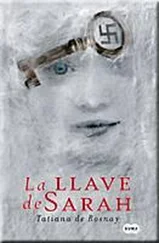

How could I have done such a thing, Colette exploded. Tracing that family, contacting that man, who in the end knew nothing of his mother’s past.

“That poor man,” echoed my sister-in-law Laure, quivering. “Imagine, now he finds out who he really is, his mother was a Jew, his entire family wiped out in Poland, his uncle starved to death. Julia should have left him alone.”

Edouard stood up abruptly, threw his hands into the air.

“My God!” he roared. “What has come over this family!” Zoë took shelter under my arm. “Julia did something brave, something generous,” he went on, quaking with anger. “She wanted to make sure that the little girl’s family knew. Knew we cared. Knew that my father cared enough to ensure Sarah Starzynski was looked after by a foster family, that she was loved.”

“Oh Father, please,” interrupted Laure. “What Julia did was pathetic. Bringing back the past is never a good idea, especially whatever happened during the war. No one wants to be reminded of that, nobody wants to think about that.”

She did not look at me, but I perceived the full weight of her animosity. I read her mind easily. Just the sort of the thing an American would do. No respect for the past. No idea of what a family secret is. No manners. No sensitivity. Uncouth, uneducated American: l’Américaine avec ses gros sabots.

“I disagree!” said Cécile, her voice shrill. “I’m glad you told me what happened, Père. It’s a horrid story, that poor little boy dying in the apartment, the little girl coming back. I think Julia was right to contact that family. After all, we did nothing we should be ashamed of.”

“Perhaps!” said Colette, her lips pinched. “But if Julia had not been so nosy, Edouard would never have mentioned it. Right?”

Edouard faced his wife. His face was cold, so was his voice.

“Colette, my father made me promise I’d never reveal what happened. I respected his wish, with difficulty, for the past sixty years. But now I am glad you know. Now I can share this with you, even if it apparently disturbs some of you.”

“Thank God Mamé knows nothing,” sighed Colette, patting her ash blond hair into place.

“Oh, Mamé knows,” piped up Zoë’s voice.

Her cheeks turned beet red but she faced us bravely.

“She told me what happened. I didn’t know about the little boy, I guess Mom didn’t want me to hear that part. But Mamé told me all about it.”

Zoë went on.

“She’s known about it since it happened, the concierge told her Sarah came back. And she said Grand-père had all these nightmares about a dead child in his room. She said it was horrible, knowing, and never being able to talk about it with her husband, her son, and later, with the family. She said it had changed my great-grandfather, that it had done something to him, something he could not talk about, even to her.”

I looked at my father-in-law. He stared at my daughter, incredulous.

“Zoë, she knew? She’s known about it all these years?”

Zoë nodded.

“Mamé said it was a dreadful secret to carry, that she never stopped thinking about the little girl, she said she was glad I now knew. She said we should have talked about it much earlier, we should have done what Mom did, we should not have waited. We should have found the little girl’s family. We were wrong to have kept it hidden. That’s what she told me. Just before her stroke.”

There was a long, painful silence.

Zoë drew herself up. She gazed at Colette, Edouard, at her aunts, at her father. At me.

“There’s something else I want to tell you,” she added, smoothly switching from French to English and accentuating her American accent. “I don’t care what some of you think. I don’t care if you think Mom was wrong, if you think Mom did something stupid. I’m really proud of what she did. How she found William, how she told him. You have no idea what it took, what it meant to her. What it means to me. And probably what it means to him. And you know what? When I grow up, I want to be like her. I want to be a mom my kids are proud of. Bonne nuit.”

She made a funny little bow, walked out of the room, and quietly closed the door.

We remained in silence for a long time. I watched Colette’s face grow stony, almost rigid. Laure checked her makeup in a pocket mirror. Cécile seemed petrified.

Bertrand had not said one word. He was facing the window, hands joined behind his back. He had not looked at me once. Or at any of us.

Edouard got up, patted my head in a tender, paternal gesture. His pale blue eyes twinkled down at me. He murmured something in French, in the crook of my ear.

“You did the right thing. You did well.”

But later on that evening, as I lay in my solitary bed, unable to read, to think, to do anything but lie back and examine the ceiling, I wondered.

I thought of William, wherever he was, trying to fit the new pieces of his life together.

I thought of the Tézac family, for once having to come out of their shell, for once having to communicate, the sad, dark secret out in the open. I thought of Bertrand turning his back to me.

“Tu as fait ce qu’il fallait. Tu as bien fait,” Edouard had said.

Was Edouard right? I did not know. I wondered, still.

Zoë opened the door, crept into my bed like a long silent puppy, nestling up to me. She took my hand, slowly kissed it, rested her head on my shoulder.

I listened to the muffled roar of the traffic on the boulevard du Montparnasse. It was getting late. Bertrand was with Amélie, no doubt. He felt so far from me, like a stranger. Like somebody I hardly knew.

Two families that I had brought together, just for today. Two families that would never be the same again.

Had I done the right thing?

I did not know what to think. I did not know what to believe.

Zoë fell asleep next to me, her slow breath tickling my cheek. I thought of the child to come, and I felt a sort of peace come over me. A peaceful feeling that soothed me for a while.

But the ache, the sadness remained.

ZOË!” I YELLED. “For God’s sake hold your sister’s hand. She is going to fall off that thing and break her neck!”

My long-legged daughter scowled at me.

“You are one hell of a paranoid mother.”

She grabbed the baby’s plump arm and shoved her back onto her tricycle. Her little legs pumped furiously along the track, Zoë hurdling behind her. The toddler gurgled with delight, craning her neck back to make sure I was watching, with the overt vanity of a two-year-old.

Читать дальше