The principal was upset that no one noticed anything in a school with so many windows. That is likely what her sister described. Perhaps the local boys turned into men and they were all confederates now so many years after the fact, the settling of an old score in a remote place that manages that kind of thing so well.

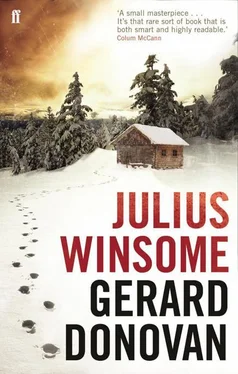

I have long believed that the grave is the end of us, and if I did not think so, I might have allowed the killing of Hobbes to pass and allow it some significance in a larger story. But he was a stone, he was stiller than a stone because even a stone moves eventually, kicked by a boot or moved by the weather or a tire, and he was lying packed in clay twenty feet from the cabin, hearing nothing, seeing nothing, tasting nothing, nothing stored in him. That twenty feet might as well have been the universe, it made no difference to him or to me. And he was dead evidently because of some pique, a stored offense over as many years.

I was not going to let that pass.

IF CLAIRE HAD A PLAN FOR MY UNDOING, SHE WAS slow and careful in its execution.

Once I was late at the repair shop and when I got home saw the steam and the flicker of candlelight in the bathroom beside the kitchen: she must have poured herself a bath in the antique tub. I had pots in there too with rubber plants and large daisies and beige tile underneath. Within the minute I heard a voice reading poetry and then calling my name, the water may have cooled and I carried some more that had boiled in a large pan on a towel to the door. She was reading a poet from France, I recognized the lines, the rhythms she captured without effort, because the French in her understood the cadences.

I heard her voice: Why don’t you pour the hot water into the tub.

It was a voice without a body that drifted through the steam. When I stepped forward, a book emerged from the mist in her hand.

Bring yourself in too, if you want, she said.

I stood inside the door and she asked me to turn the pages for her, an old hardcover, with poems on one side and drawings in thin orange pencil scattered through the pages. I knelt and read in the candles from different poems as she lay in the foam. This poet was killed in the Great War, I said, and there were many in the book who died in that conflict, some known, some not, the words collected from boxes and envelopes, from lonely wives and anguished brothers. She grew still in the hot water surrounded by plants and the perfume of the soap and listened to those voices out of time.

I rested my hand on the edge and wondered if she saw the old English in my face the way I saw the old French in hers, and if such differences mattered. I thought that if she touched me I would disappear too like those vanished men who brought such differences with them into hell.

She said she was tired, asked if she could stay a while.

My bedroom was small and white and the bed-covers were orange and yellow. The mattress leaned over the edge of the wooden frame that lay close to the floor and had a dip in it where I lay every night. She said she could tell I had not had any visitors in a while, and perhaps she wondered if anyone had ever slept in that bed but me. The sheets were clean and whiffed of lavender soap. I had boxes stacked by the walls and a gramophone balanced on three of them over a length of cut carpet, plugged into an outlet shared by the small lamp on another box by the bed. It was my bedroom from the start. My father slept in the room opposite, what was now occupied by shelves and books. We lay together and she slipped the towel off and moved the shirt from my chest.

That night, as in a few other summer nights to come, we warmed each other under the covers, though in the very early hours she rose and went outside to the stove and the chair with the red cushion. I thought I heard her cry, but it may have been the night. I knew what drew her to that chair: you sat in it and wanted to think, you wanted to read something with the whiff of pipe smoke but not from any one thing: even when I held the cushion to my face, the phantom of the pipe produced my father generally about me.

* * *

If Claire had a plan for my undoing, she did not stick to it. The following evening she held my hands and placed a small book into them, one I had not seen before, poems by John Donne. On the preface page she had written some lines.

All that silence waves across you, Julius, like the long grass.

You make me feel like a poet.

I was surprised to find myself the subject of such fine words and did not know what to say. She stroked my hands and leaned closer, her whispers soft in the firelight:

You never say how you feel, but I feel affection everywhere in you. Maybe that’s what matters, do you think?

If solitude could be measured I suppose it might have been in the way I was happy to see her despite being happy anyway. Now I was more than happy, nothing that I had a word for, to have all this company in my life all of a sudden. She felt to me like those first drops of rain that make you wait in the doorstep with your coat above your head, wondering if this is a small cloud or something longer. In response to her question I simply nodded, because I didn’t know what to say. Being given something was new and I hadn’t the natural words for the thanks I meant. Her hands slipped away.

With Claire lying beside me that night I heard a fox and plenty of coyotes howling in groups across the fields, and closer to the house the guineas in the trees flapped up into little rows; the roosters babbled in sudden fright at a creature creeping through the undergrowth where they perched, sometimes a scream of pain and fright, something leaped on in the night. The walls sparked and creaked, most of which must have been the wood contracting in the cooler temperatures, but other noises too, things moving, or Hobbes, I wasn’t sure.

In the morning I woke with his face in mine: she must have left early for the town.

Love, or words of tenderness and affection, yes, she had spoken them to me, and I think now that I was meant to respond in kind: yet I was not used to it, how saying a word meant that the feeling was any less or more when it was given a name, but I should have said enough to let her know that I was thankful for her company, that I missed her when she was not about, and if that was love, then we would be fine. Claire never again said something in order to discover what I might say back, or what might be offered in return. I should have known that people can sometimes come close enough to discover that they are strangers.

After that night, she visited less and stayed shorter. The absence of someone comes like a new season, first only in pieces: you see the absence in them long before they leave. In Claire it started with long glances and silence and arrived fully only after she was gone.

THAT DAY WE WENT PICKING BLACKBERRIES ALONG the sloping meadows and wild flowers near Eagle Lake—we made a trip of it with Hobbes in the truck. If there is only one field in the world, it must surely be found in Maine, a hay-green slope to a blue lake that I knew since a boy: I ran down it and threw a hawthorn stick from England that my grandfather brought back, and Hobbes didn’t swim after it. We watched it float away.

Well that’s that, I said.

Claire lay on the grass and drew him in pencil and charcoal. I tipped a bottle of ale sideways for a drink, felt the sun easy on my face, felt that I was happy. That’s it, she soon said, and handed me the drawing: just one glance told me the same as a long stare, that she had captured the living dog and his character, matched him to the whisker. I put the page on the grass without a word, and afterwards stored it behind the seat for safety.

Читать дальше