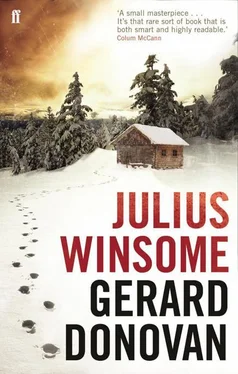

Gerard Donovan

JULIUS WINSOME

A Novel

for Doug Swanson and

Christina Nalty

Those who live the longest and those who die the soonest lose the same thing. The present is all that they can give up, since that is all you have.

—MARCUS AURELIUS

PART ONE

October 30th–November 2nd

I THINK I HEARD THE SHOT.

It was a cold afternoon at the end of October, and I was in my chair reading by the wood stove in my cabin. In these woods many men roam with guns, mostly in the stretches away from where people live, and their shots spray like pepper across the sky, especially on the first day of the rifle hunting season when people from Fort Kent and smaller towns bring long guns in their trucks up this way to hunt deer and bear.

But the metal punch that rang across the forest seemed a lot closer, less than a mile off if it’s the sound that killed him, but the truth is that I have imagined hearing it so many times since, rewound the tape of those moments so often, that I cannot tell anymore the true sound of the rifle from the phantom of my thoughts.

That was close, I said, and opened the woodstove and shoved in another log, closing it before the smoke poured out and filled the room.

Most of the hunters, even the beginners, kept to the open forest, farther west in the North Maine Woods and to the Canadian border, but a good rifle carries far, and the distance can be tricky to figure without walls and roads.

It still sounded too close. The seasoned hunters knew where I lived and where all the cabins were in the woods, some in the open, some hidden. They knew not to discharge a weapon, that bullets will travel until they hit something.

I had a good fire going and my legs were warm, and I finished the short story by Chekhov where a girl cannot sleep and the baby won’t stop crying, and was so caught up in it that I didn’t notice my dog was gone. I had let him out a few minutes before and it was nothing new for him to wander off, though mostly he stayed a hundred yards or so from the cabin in a big circle, his territory, the thing he owned.

I went to the door and called for him, thinking again that the sound was a bit close to the house, and then I checked again ten minutes later and still couldn’t find my dog, he didn’t come in when I called, louder each time, and when I walked to the edge of the woods and whistled, cupped my hands around my mouth and shouted, there was no sign, no brown shape breaking out of the undergrowth toward me as he always did when summoned.

The wind was cold and I closed the door and slid the towel on the floor against it to block the draft. Then I did something I rarely do in the winter months: I checked the clock.

It was four minutes past three.

NOVEMBER ARRIVES IN NORTHERN MAINE ON A COLD wind from Canada that knifes unfiltered through the thinned forest, drapes snow along the river banks and over the slope of hills. It’s lonely up here, not just in fall and winter but all the time; the weather is gray and hard and the spaces are long and hard, and that north wind blows through every space unmercifully, rattling the syllables out of your sentences sometimes.

I grew up in these woods, the forest land at the western edges of the St. John Valley that borders the Canadian province of New Brunswick and runs along the banks and south of the St. John River with its rolling hills and small, back settlement towns. My grandfather was French Acadian, as was my mother, and for reasons unknown to me he built the cabin miles away from the French, on tree-covered land close to where the great woods began in the western part of the valley. At the time it was even more remote than now, and strange because those people stuck together: most who lived in those settlement towns were descended from the French Acadians expelled by the British from Nova Scotia in 1755. Some went south to Louisiana, the rest moved eventually to Northern Maine, these people of extremes, my father said, people of far south and north.

It was strange also because of the winters. He built the cabin on two acres of cleared land, with the woods on all sides, and my father added a large barn, bigger than the cabin, where he kept all his tools and the truck and anything fragile or easily lost that would not survive the six winter months outside. The woods that ringed the house were formed of evergreens and leaf-shedders both—pines, oak, spruce, hemlock, maple—and so the trees circling the cabin seemed to step back, retreat in pieces as the leaves turned yellow and deep rust, shredding off like dead skin as September came, crinkling yellow along the floor of the woods as October arrived, and blowing away into November.

The cabin came from my mother’s French side, my father being English, and I inherited it through her by way of him. He told me that I wouldn’t believe it if I saw it, that the valley was like the rolling midlands of England, but the tongue that echoed in these hills was French, not English. And that was another strange decision, an Acadian woman marrying English, but she was her own woman I am told, and anyway they are not people you tell what to do.

The cabin blends into the woods, or the woods into the cabin. One moment you are in forest stepping over a branch, the next step puts you walking across a porch, and you want to be careful. Many men live in these woods who cannot live anywhere else; they live alone and are tuned close to any offense you might give them, best to keep your manners about you, and even better to have nothing to say at all. They come up north and wait out life, or they were here anyway and stayed for the same reason. Such men live at the end of all the long lanes in the world, and in reaching a place like this they have run out of country they can’t live in. They have no choice but to build, and so they go as far out of the way as they can even here, in the deep shade of the trees. I lived far from the nearest of them, the closest cabins three miles to the west and north of me.

In summer I kept a bed of flowers along the edge of the clearing, about thirty feet by three, filled with nasturtiums, marigolds, lilies, and foxglove, and every year I added to the small lawn with sown grass that grew to a hot green carpet in the summer where I could lie down and smell the flowers and taste the blue sky. But this winter had come late; we had a strange, warmer south wind for most of October, and some of the flowers were still alive with their smell, way past season. I’d covered them with black plastic bags pulled out to little tents on poles to keep them alive through the odd night frost, hoping to keep their color another week and shorten the gray months ahead. They had made my life bright in summer and I wanted to help them. But in the last couple of days the temperatures had fallen, and soon these survivors would retreat too, find the safety of the soil and sleep in their seed under the vice-grips of deep winter.

* * *

Except for my dog I lived on my own, for I had never married, though I think I came near once, and so even the silences here were mine. It was a place built around silences: my father was a reader of books, and spreading along the walls from the wood stove stretched the long bookcases from the living room and on to the kitchen at the back and right and left to both bedrooms, four shelves high, holding every book he ever owned or read, which was the same thing, for my father did indeed read everything. I was surrounded therefore by 3,282 books, leatherbound, first editions, paperbacks, all in good condition, arranged by alphabet and recorded on lists written in fountain pen. And because the bookcase ringed the entire cabin—and since some rooms were darker and colder than others, being distant from the woodstove—there were also warm novels and cold novels. Many of the cold novels had authors whose last names began with letters after “J” and before “M,” so writers like Johnson and Joyce, Malory and Owen lived back near the bedrooms. My father called it an outpost of Alexandria in Maine, after the Greek library, and he liked nothing better when he came in after work than to stretch his socks to the fire until they steamed, and in his thick sweater and smoking his pipe then turn to me and ask for a particular book, and I remembered the cold pages in my hands, carrying to my father the volume he wanted, watching it warm under his eyes by the fire, and when he was finished I carried the warm book back to its shelf and slid it in, a tighter fit because it had grown slightly in the heat.

Читать дальше