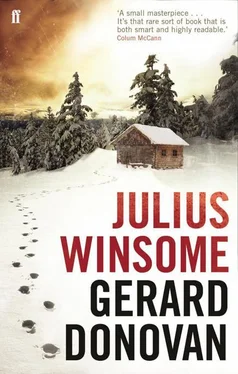

It is also the time when an entire day squeezes in through the single bedroom window, and I stayed in bed most of the day, the blankets warmer than the air.

* * *

But I had things to do first. I ran to the woodpile and hauled in some logs before they got damp, and I covered the rest with green tarpaulin, folded once. After a meal of potatoes and fried fish I went out again with the flashlight and walked the flowerbeds and said goodbye to the last shades of pink and red, since by morning they would be cast under white, and soon covered. I hoped that the long snow of winter, now just begun, would keep my friend warm. I leaned to the ground and sank my fingers into the snowfall above where he lay.

I stood in the clearing as it whitened and looked up into the broken pieces of the night around the flakes.

Winter.

PART TWO

Night of November 2nd

THAT NIGHT IT WAS AS IF THE WIND SIMPLY BLEW through the house and blankets, as if nothing blocked the weather from my body. I lay in bed, waiting for a strain of heat to measure me and fit me into sleep. I heard noises, surely the crackling chill in the timbers of the cabin. Unless: wait, was that Hobbes at the door scratching? Had he somehow woken up and clawed his way out of the flower beds? I had heard of such things in history books, people in coffins waking up, wood found in their fingernails. That, or there were men about in the dark. If so, no matter: before lying down I brought the Enfield into the bedroom and leaned it against the wall.

I rose, let the cover fall away to the coat, and made for the door with the rifle loose in one hand, but when I opened it, one knife flew at my face, my hands, my feet, three instant cold blades from the wind. I shielded my eyes to no avail: no dog anywhere in sight, no paws and a head waiting to come in. I lingered to be sure, stood there for a minute before going back inside and pulling on the wool socks and a sweater under the coat. The wind must have infected me now, I shook that hard. I dressed myself fully by the bed. To fall asleep and be defenseless, to lie still while the forest swarmed around, that could not be. Better covered now, I was off again, this time all the way outside, to the grave.

Bending close I saw nothing that showed Hobbes had freed himself. I traced no evidence of even weak marks, the softening tracks of a running dog. So the howl and scratch at the door was only the cold after all. I stood at the forest edge wrapped in the coat and looked back at the cabin: the weak light of the frigid bedroom I had just left glimmered in the cracks of the side window, otherwise all was black, open to the elements but for a few inches of timber and a lining of books.

I waited for nothing. And nothing arrived. A deep ice stole its way into my heart. I felt it settle in and numb the valves and quiet the wind that blew inside my frame, heard it set upon my bones and breathe silence into the brittle spaces, everything that was broken. At that moment my heart knew the peace of cold. I gave up on my friend, and the night watch was done, for only his spirit would ever come to me again.

IF THE NOISE WAS NOT FROM THE GRAVE, THE UNEASE was elsewhere, and I could not stay out here standing sentry for that long. The suspicion that drew me out was perhaps all that could be called grave tonight: what had stayed at the back of my mind, a worry like wings.

I did not want to suspect Claire of anything, and did not, until I remembered our recent conversation on the street when she seemed to sense that all was not well with me. How would she know? Was her hand in this? Perhaps she belonged so completely now to another man that she decided to remove anything from that summer that still attached itself to me, and all that was left was Hobbes.

Such a thought, that Claire brought a gun out along the trails to my cabin and ended the life of the dog she helped rescue. It was well beyond my means to harm her, or any woman—and in that event my father would never have tolerated such a thing—but the thoughts would not disperse from my mind. Had she killed him?

Though the cold was something fierce, I hugged the coat about me more and leaned into the sheltered side of a tree trunk.

TO LOOK FOR EVIDENCE MEANT SHARPENING THE details of what was already known, re-seeing what was already seen. And it slowly came to me, what was bothering me, some evidence of a trick she played with others to bring this dog into my life and then take him away. I resolved however to think things over before anything else was done.

* * *

The first evidence of guilt was the way she turned up at the cabin that day in early summer. She walked past the flowers that stained the grass blue and yellow under the Maine sky, wide and shallow and ice blue. I was in the kitchen reading, and the wind blew from the south through the open window and through all the rooms, seeking out the last smells and shadows of spring, and the new summer grazed my skin with a warm whisper, its first word. I rose from the armchair when I heard her: my face had been buried in a book and now it filled the glass as I watched.

Some hens ran after each other in the sunlight under the smell of burning pine and past the truck. I stepped out onto the porch under smoke that swept down from the chimney.

She said, I was in the area. I don’t know, I got lost I think.

It made perfect sense to me then, as if she had just raised her wrist with a watch on it and told me the time of day in the middle of the street back in the town.

If that’s so, I said, why don’t you come in then and have some of the tea.

To her the walls must have looked like they were made out of books, leather that stretched along the eye. I walked behind her to the sink and watched the house fit around her as she stood under the door frame that separated the large first room from the second. She glanced at the oak floor and the wood stove, watched the fountain outside the small side window: a bird wriggled through the water. She whispered how few of the paintings had people in them, the ones on the walls hung by my father and grandfather, one a brown landscape of bare trees, others of seashores, gardens, haystacks, climbing above the bookshelves.

I went off to play a record, some piano music. I should have pressed my question at once about this sudden visit. Outside it fell down some short rain, the flowers dripped, and the notes dripped from the bedroom, a tune by Satie from my father’s days. I poured the boiling water onto the tea bags and handed her a mug with a spoon.

You haven’t changed much, she said.

I said, I don’t think we’ve met.

No, it’s my sister. She was a few classes behind you in school when you went there. She described you.

Though it made little sense, it was what she said. When the shower ended the sun shone through the wet glass and warmed the red roofs in one of the paintings. I wondered why she got lost here and not somewhere else but did not want to ask, since people usually choose the place they get lost in and she must have had her reasons. Anyway I had much of the rest of the day free, and all that was left was to run into the town and pick up carrots and fish and some bread.

Was I rude to just turn up like this, she said.

I asked her what other way there was to turn up.

Her car was in the woods, she said, a half mile away where the road was still wide enough: she wanted to go for a long walk today and kept going. She had to go home now. That must have been her first mission, to see the cabin, to count how many lived here, a short count as it turned out.

I told her I would bring her back as this was no place for walking in once evening made its way through the trees, even in summer. The odd large creature made its way across the river from Canada and might not take well to the surprise. We made our way under the leaves, mostly in silence along a brown line that wound itself into the undergrowth. The way was narrow enough to tell me that the last part of the journey had been too close for her to drive: the branches touched each other across it. In the truck it was just a matter of keeping going for the half mile through everything. It was clever of her I suppose, to keep her car where it would not be seen.

Читать дальше