What I was least able to understand in Paul's story, after all that, was the fact that in early 1939 — be it because the position of a German tutor in France in times that were growing more difficult was no longer tenable, or out of blind rage or even a sort of perversion — he went back to Germany, to the capital of the Reich, to Berlin, a city with which he was quite unfamiliar. There he took an office job at a garage in Oranienburg, and a few months later he was called up; those who were only three-quarter Aryans were apparently included in the muster. He served, if that is the word, for six years, in the motorized artillery, variously stationed in the Greater German homeland and in the several countries that were occupied. He was in Poland, Belgium, France, the Balkans, Russia and the Mediterranean, and doubtless saw more than

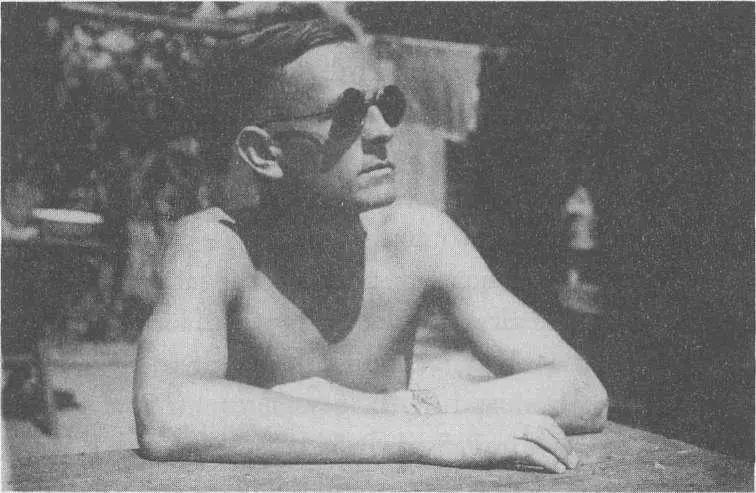

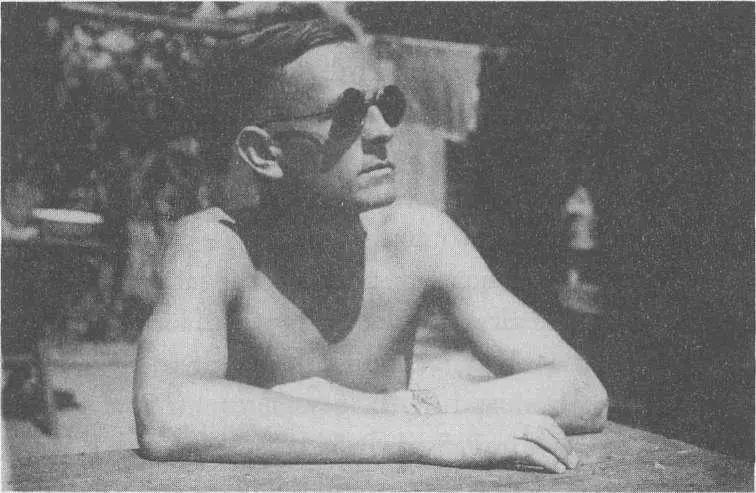

any heart or eye can bear. The seasons and the years came and went. A Walloon autumn was followed by an unending white winter near Berdichev, spring in the Departement Haute-Saóne, summer on the coast of Dalmatia or in Romania, and always, as Paul wrote under this photograph,

one was, as the crow flies, about 2,000 km away — but from where? — and day by day, hour by hour, with every beat of the pulse, one lost more and more of one's qualities, became less comprehensible to oneself, increasingly abstract.

Paul's return to Germany in 1939 was an aberration, said Mme Landau, as was his return to S after the war, and to his teaching life in a place where he had been shown the door. Of course, she added, I understand why he was drawn back to school. He was quite simply born to teach children — a veritable Melammed, who could start from nothing and hold the most inspiring of lessons, as you yourself have described to me. And furthermore, as a good teacher he would have believed that one could consider those twelve wretched years over and done with, and simply turn the page and begin afresh. But that is no more than half the explanation, at most. What moved and perhaps even forced Paul to return, in 1939 and in 1945, was the fact that he was a German to the marrow, profoundly attached to his native land in the foothills of the Alps, and even to that miserable place S as well, which in fact he loathed and, deep within himself, of that I am quite sure, said Mme Landau, would have been pleased to see destroyed and obliterated, together with the townspeople, whom he found so utterly repugnant. Paul, said Mme Landau, could not abide the new flat that he was more or less forced to move into shortly before he retired, when the wonderful old Lerchenmiiller house was pulled down to make way for a hideous block of flats; but even so, remarkably, in all of those last twelve years that he was living here in Yverdon he could never bring himself to give up that flat. Quite the contrary, in fact: he would make a special journey to S several times a year especially to see that all was in order, as he put it. Whenever he returned from one of those expeditions, which generally took just two days, he would always be in the gloomiest of spirits, and in his childishly appealing way he would rue the fact that, to his own detriment, he had once again ignored my urgent advice not to go there any more.

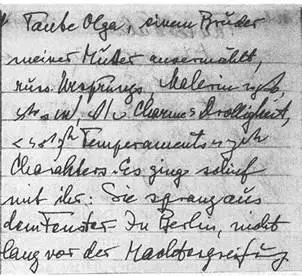

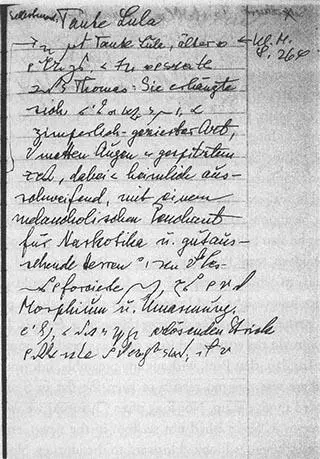

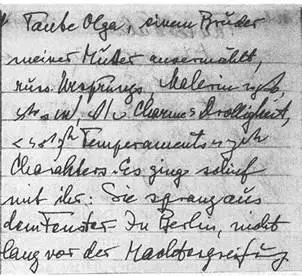

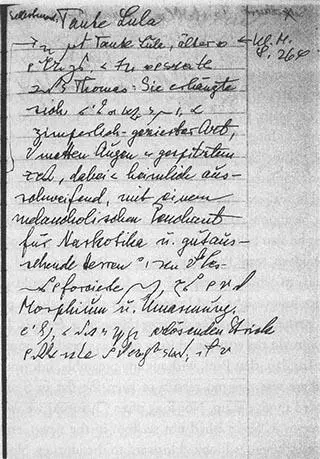

Here in Bonlieu, Mme Landau told me on another occasion, Paul spent a lot of time gardening, which I think he loved more than anything else. After we had left Salins and our decision had been taken that from now on he would live in Bonlieu, he asked me if he might take the garden in hand, which at that time was fairly neglected. And Paul really did transform the garden, in a quite spectacular manner. The young trees, the flowers, the plants and climbers, the shady ivy beds, the rhododendrons, the roses, the shrubs and perennials — they all grew, not a bare patch anywhere. Every afternoon, weather permitting, said Mme Landau, Paul was busy in the garden. But sometimes he would simply sit for a while, gazing at the greenery that burgeoned all around him. The doctor who had operated on his cataracts had advised him that peaceful spells spent simply looking at the leaves would protect and improve his eyesight. Not, of course, that Paul took any notice whatsoever of the doctor's orders at night, said Mme Landau. His light was always on till the small hours. He read and read — Altenberg, Trakl, Wittgenstein, Friedell, Hasenclever, Toller, Tucholsky, Klaus Mann, Ossietzky, Benjamin, Koestler and Zweig: almost all of them writers who had taken their own lives or had been close to doing so. He copied out passages into notebooks which give a good idea of how much the lives of these particular authors interested him. Paul copied out hundreds of pages, mostly in Gabelsberg shorthand because otherwise he would not have been able to write fast enough, and time and again one comes across stories of suicide. It seemed to me, said

Mme Landau, handing, me the black oilcloth books, as if Paul had been gathering evidence, the mounting weight of

which, as his investigations proceeded, finally convinced him that he belonged to the exiles and not to the people of S.

In early 1982, the condition of Paul's eyes began to deteriorate. Soon all he could see were fragmented or shattered images. No second operation was going to be possible; Paul bore the fact with equanimity, said Mme Landau, and always looked back with immense gratitude to the eight years of light that the Berne operation had afforded him. If he paused to consider, Paul had said to her shortly after being given an extremely unfavourable prognosis, that as a child he had already been troubled with little dark patches and pearldrop shapes before his eyes, and had always been afraid that he would go blind at any time, then it was amazing, really, that his eyes had done him such good service for quite so long. The fact was, said Mme Landau, that Paul's whole manner at that time was extraordinarily composed as he contemplated the mouse-grey (his word) prospect before him. He realized then that the world he was about to enter might be a more confined one than that he had hitherto lived in, but he also believed there would be a certain sense of ease. I offered to read Paul the whole of Pestalozzi, said Mme Landau, to which he replied that for that he would gladly sacrifice his eyesight, and I should start right away, for preference, perhaps, with The Evening Hour of a Hermit. It was some time in the autumn, during one such reading hour, said Mme Landau, that Paul, without any preamble, informed me that there was now no reason to keep the fiat in S and he proposed to give it up. Not long after Christmas we went to S to see to it. Since I had not set foot in the new Germany, I had misgivings as I looked forward to the journey. No snow had fallen, there was no sign anywhere of any winter tourism, and when we got out at S I felt as if we had arrived at the end of the world, and experienced so uncanny a premonition that I should have liked most of all to turn back on the spot. Paul's flat was cold and dusty and full of the past. For two or three days we busied ourselves in it aimlessly. On the third day a spell of mild fóhn weather set in, quite unusual for the time of year. The pine forests were black on the mountainsides, the windows gleamed like lead, and the sky was so low and dark, one expected ink to run out of it any moment. The pain in my temples was so dreadful that I had to lie down, and I well remember that, when the aspirin Paul had given me gradually began to take effect, two strange, sinister patches began to move behind my eyelids, furtively. It was not till dusk that I woke; though on that day it was as early as three. Paul had covered me with a blanket, but he himself was nowhere to be seen. As I stood, irresolute in the hall, I noticed that Paul's windcheater was missing, which, as he had happened to mention that morning, had been hanging there for almost forty years. I knew at that moment that Paul had gone out, wearing that jacket, and that I would never see him alive again. So, in a way, I was ready when the doorbell rang soon after. It was only the manner in which he died, a death so inconceivable to me, that robbed me of my self-control at first; yet, as I soon realized, it was for Paul a perfectly logical step. Railways had always meant a great deal to him — perhaps he felt they were headed for death. Timetables and directories, all the logistics of railways, had at times become an obsession with him, as his flat in S showed. I can still see the Màrklin model railway he had laid out on a deal table in the spare north-facing room: to me it is the very image and symbol of Paul's German tragedy. When Mme Landau said this, I thought of the stations, tracks, goods depots and signal boxes that Paul had so often drawn on the blackboard and which we had to copy into our exercise books as carefully as we could. It is hard, said Mme Landau, when I told her about those railway lessons, in the end it is hard to know what it is that

Читать дальше